Master System Goes Deep

It’s 1989, the playground is ruled by Zelda, Mario and the whispered secrets from Nintendo Power. But for us few Master System loyalists, clutching to our Sega Challenge Newsletters, we knew our system was the home of deeper experiences and more innovative genre mash-ups. We had already cut our teeth on Phantasy Star a whole year before Nintendo was begging their players to check out Dragon Warrior. While we were mapping out the massive smooth scrolling dungeons of Corona Tower, NES players were relying on the training wheel guides uncle Mario had packed into their free RPGs that Nintendo could barely give away.

The NES was a console first and arcade port machine second but Sega had a direct line from the arcade into the Master System that delivered a ton of innovation not seen on the NES. Wonder Boy was one series in particular that took its early cutesy arcade platformer and mashed it up with the action RPG genre that was brewing in Japan in the early 80s and delivered the perfect blend with Wonder Boy in Monster Land.

At first glance, it looked like another arcade platformer, complete with a time limit and a linear path. But it was so much more. This was a game where you collected gold from defeated enemies not just for points, but to actively purchase better swords, sturdier shields, and magic spells. It was one of the first console games to successfully blend the satisfying jump-and-slash action of a platformer with a persistent RPG-style equipment and upgrade system, creating a template that would influence countless action-adventures to come.

This shift was revolutionary. It moved the challenge from pure strategy to active player skill. Instead of selecting attack from a menu, you were the attack, pressing the button to swing the sword in real-time. Combat and exploration became seamless, demanding timing and positioning just as much as a high level. This move from passive, menu-driven commands to direct, kinetic control made the adventures feel faster, more dangerous, and infinitely more immersive. Jumping into this adventure and finally conquering the Meka Dragon felt like an epic accomplishment. We couldn’t get enough and we couldn’t wait for Sega to deliver more of this formula to our living rooms.

We waited patiently because we knew that, when Sega delivers, it would deliver something mind blowing. And deliver Sega did! When the sequel dropped, Wonder Boy III: Dragon’s Trap didn’t just give us an action RPG rehash, they gave us a Metroidvania for the ages that blew anything on the NES out of the water. With its core mechanic of animal transformation, the action RPG mechanics were brilliantly married with levels that were now designed as puzzles to solve and not just backgrounds to explore.

What a Horrible Night to Have a Curse

And when we finally got our chance to jump back into Wonder Boy’s world we didn’t have to miss a beat. The sequel began right where we left off in Monster Land with the boss run to the Meka Dragon. We didn’t start a new story, we began by finishing the old one. We were the hero, fully powered up, storming the final castle for one last glorious battle. You confront the Meka Dragon and strike the killing blow, reliving the glory we experienced a mere year ago.

But this victory was now a prelude to a bigger game. In its death throes, the dragon inflicts a legendary curse. In a flash, your hero is violently transformed into a Lizard-Man. This was not a simple power-reset, it was a transformation that brought you to face your most profound challenge yet. All your legendary equipment was stripped away, forcing you to begin your quest again vulnerable but determined to reclaim your glory.

You escape the collapsing castle as a lowly monster and the game truly begins with your quest to find the Salamander Cross and break the curse. The developers brilliantly inverted the idea of a sequel, using a moment of loss to give an immediate, personal, and powerful motivation to the player. It was an invitation to embark on a unique journey where the hero must relearn what it means to be powerful.

A Bit of Westone Wonder

To understand how The Dragon’s Trap came to be, we have to jump into the most convoluted story in 8-bit history. The Wonder Boy series was not, strictly speaking, a Sega exclusive. Even though the series had many flagship titles for the Master System, games from the series also showed up on both NES and TurboGrafx-16 under different names.

The creative soul of Wonder Boy was a developer named Westone. But Westone was not an internal Sega studio. They were a separate entity and their publishing deal with Sega was the key that allowed them to port the franchise to other systems. The deal was that Westone retained ownership of the game’s copyrights, its source code and all its core designs. Sega, as the publisher, retained the trademarks. Sega owned the brand Wonder Boy and the likeness of the characters, but Westone owned the engine and mechanics of the game itself.

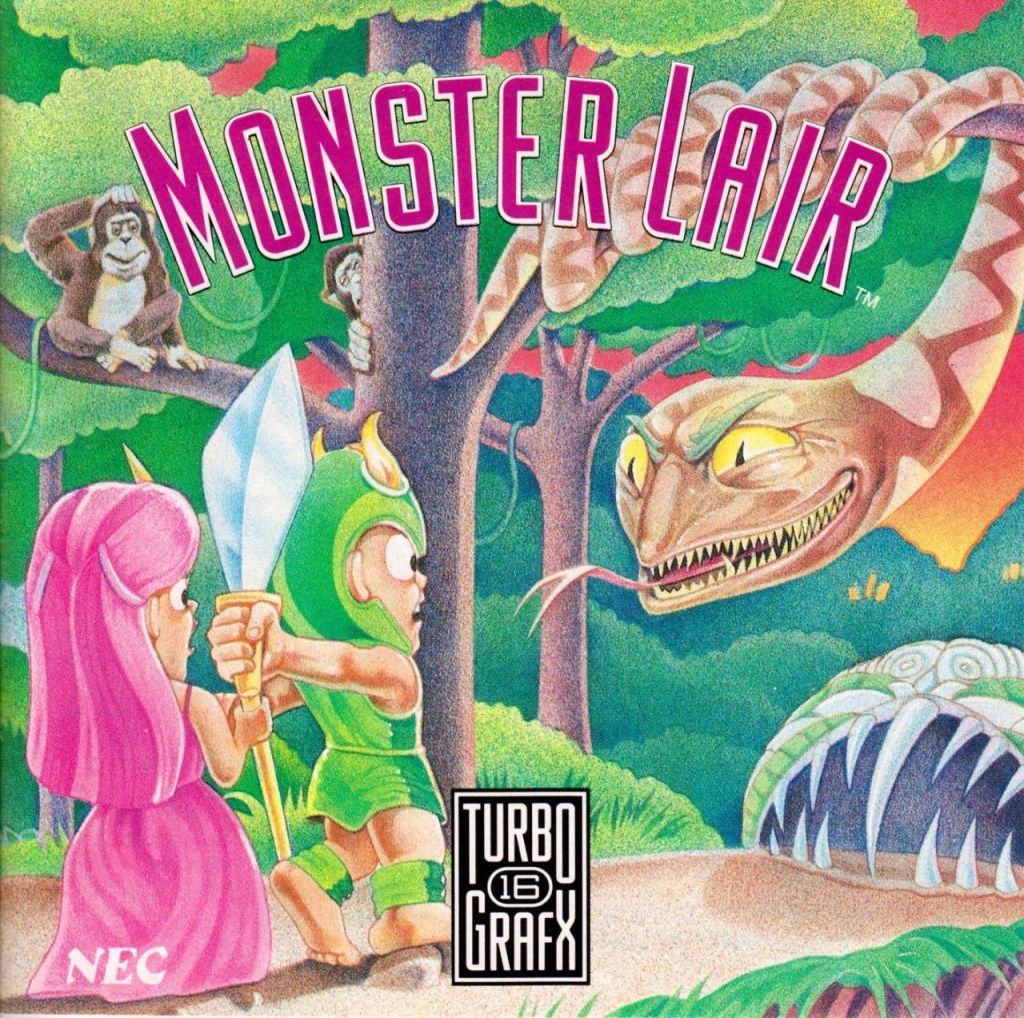

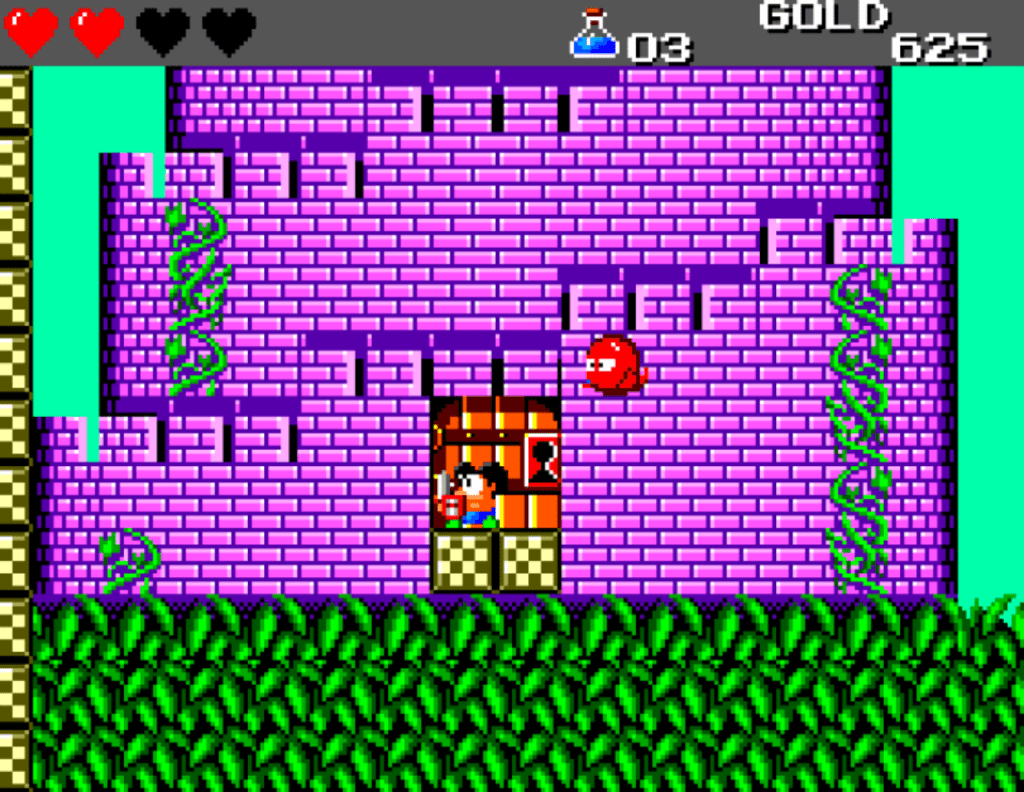

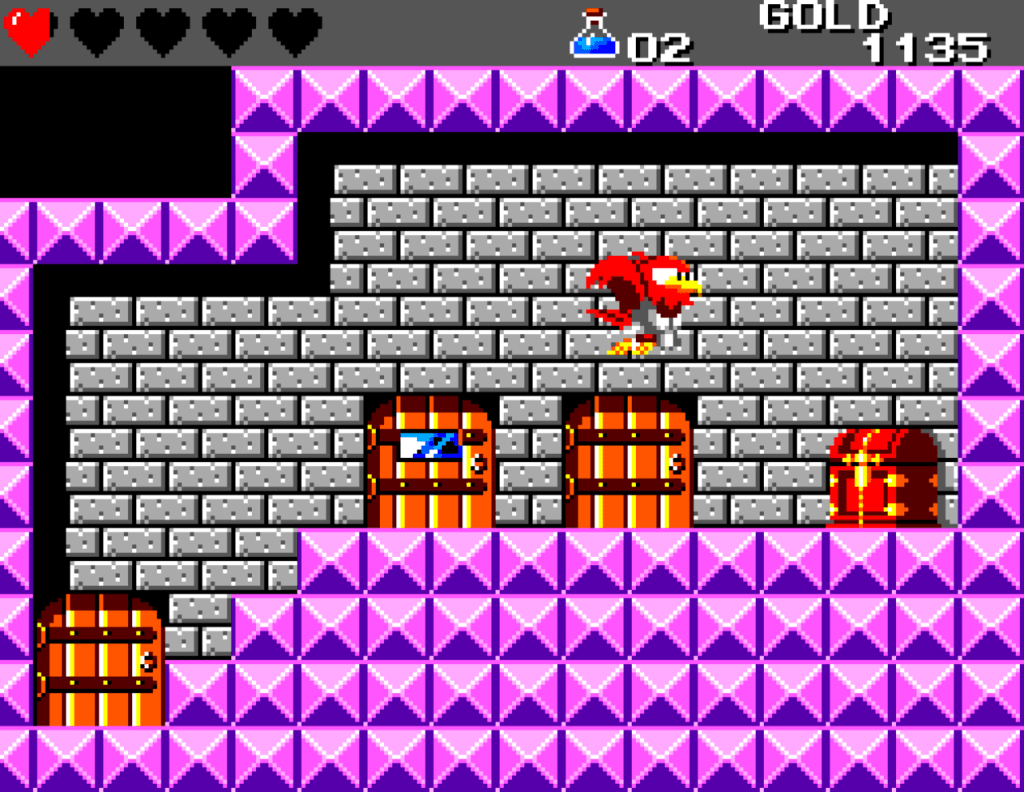

This bizarre arrangement meant Westone could legally license its gameplay mechanics to Sega’s direct competitors. It’s why the original Wonder Boy was licensed to Hudson Soft, who re-skinned it for the NES as Hudson’s Adventure Island, replacing the hero with Master Higgins. And it’s the exact same reason Westone, again owning the core design, licensed The Dragon’s Trap to Hudson Soft for NEC’s TurboGrafx-16. In North America, it was released as Dragon’s Curse. It was the exact same Westone-developed game with new sprites. Westone was, in effect, a brilliant ghost-developer, selling its designs to competing publishers. So when Dragon’s Trap came to the Master System, it had to stand out amongst its own fellow Wonder Boy clones.

Wonder Boy Grows Up

The Dragon’s Trap was the perfection of a formula that was an evolution of a design that Westone had initiated two years earlier. The true prequel, and the foundational blueprint for the entire saga, was 1987’s Wonder Boy in Monster Land. This game marked a drastic departure from the original 1986 Wonder Boy, which had been a linear, arcade platformer built on creating a feeling of pressure where the player couldn’t stop moving. In 1987, Westone abandoned the grass skirt and stone axes for a medieval world of swords and shields, creating the series’ definitive pivot from pure platformer to action-role-playing game.

This arcade-RPG design introduced the core mechanics that would define the series for the next decade. Defeating enemies for gold, buying items in shops and a light RPG system where purchasing new equipment provided tangible statistical upgrades were now the hallmarks of the series. However, Monster Land was still beholden to its arcade origins. It was effectively an RPG-on-a-clock, shackled by an hourglass timer which constantly drained, which was a remnant of the first game’s pressure design, forcing the player to move quickly rather than explore. It was a contradiction of an RPG that encouraged slow growth but an arcade cabinet that demanded high player turnover.

This is where Wonder Boy III: The Dragon’s Trap changed history. Unlike its predecessors, it was a Master System exclusive, not an arcade port. By designing exclusively for the console, Westone was finally free from the coin-drop philosophy and could scrap the timer entirely.

Without the ticking clock, the formula evolved from a linear dash into a true free-roaming adventure set in a single, large, interconnected world. The leap from Monster Land to Dragon’s Trap was the leap from a game of stats to one of environmental exploration. In Monster Land progression was gated by stats but in Dragon’s Trap progression is gated by abilities where you had to gain the power to fly, swim, or climb to physically reach the next area. It was an early example of a Merroidvania that was years ahead of its time.

But unlike most Metroidvania’s, which rely on item gating, your hero becomes the key. Each time you defeat a boss dragon, you’re cursed into a new animal form and each form has unique abilities that unlock new parts of the world. The Lizard-Man is the default form, with a ranged fire-breath attack. The Mouse-Man is tiny and weak, but he could walk on special mouse blocks on walls and ceilings, opening secret paths. The Piranha-Man is the underwater specialist, the only form that could swim freely to explore places like the sunken ship. The Lion-Man is the master swordsman, whose powerful downward sword arc could break blocks below and hit enemies above. Finally, the Hawk-Man is the aerial ace, able to fly and open up the entire world. Later, you’d find special rooms that let you transform at will, turning the entire interconnected world into a backtracking-and-exploration puzzle. This created a rich, engaging and player-driven exploration loop that was light years ahead of its 8-bit rivals.

The Final Word

Wonder Boy III: The Dragon’s Trap is far more than a cult classic for an obscure 8-bit console. It’s a design landmark, marking the deliberate, console-focused shift from the linear Arcade-RPG of Monster Land to the non-linear, exploration-based Metroidvania formula. Dragon Trap’s perfection was proven when it was remade in 2017 with nearly the exact same gameplay and level design. The fact that a modern developer could release that original 1989 gameplay to universal acclaim proves that its core design was, and remains, flawless.

Dragon’s Trap is a testament to the fact that truly elegant design is timeless. The game’s 1989 gameplay doesn’t feel retro, it feels foundational. The Dragon’s Trap endures not as a relic of the 8-bit era, but as a definitive blueprint for Metroidvanias, as perfect and compelling today as it was generations ago. It is the definitive expression of the series’ long evolution, the moment the formula was perfected and set in stone.

Leave a comment