The Birth of Esports

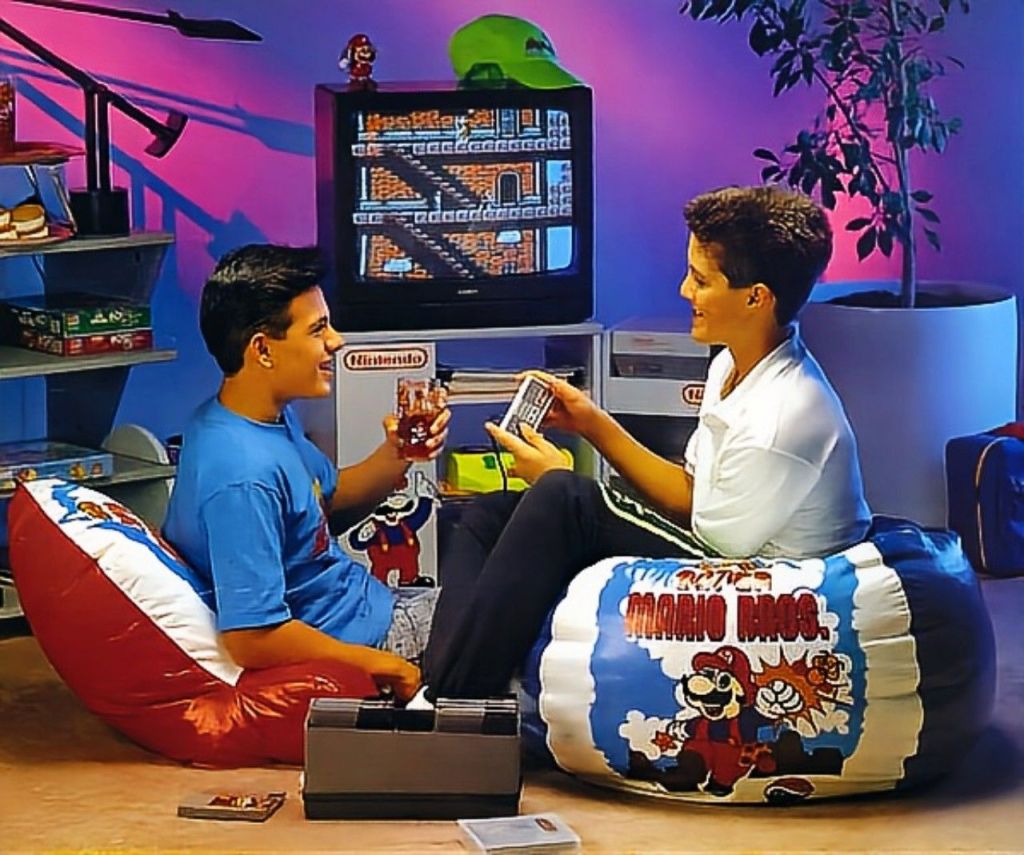

In the Winter of 1989, The Wizard changed everything. A video game road trip and one boy’s ability to see beyond the game into its deepest secrets sealed our fates. From then on, we didn’t just want to learn how to beat games, we wanted to break them and prove to the world that we were the best. Every kid in America went home that night and looked at their NES with new eyes, dreaming of glory.

What made this moment so special was that the fantasy didn’t stay on the screen. Rumors started flying around the schoolyard that the tournament from the movie was actually coming to cities around the county. The idea that Nintendo was going to build a stage for us to perform on was almost too much to handle. We were no longer just isolated kids playing with toys, we were suddenly prospective athletes waiting for the season to start.

This competitive fire was the fuel for the 1990 Nintendo World Championships (NWC). It was a perfectly timed event that capitalized on the hype to create something historic. It was a once-in-a-lifetime moment where corporate strategy, Hollywood myth-making, and the drive of gamers collided to create the first mainstream video game tournament. However, when we look back at some of the old Nintendo news letters the road to the NWC didn’t start in Hollywood or New York, but on the highways of America’s northern neighbour, Canada.

The Wizard: 90 Minutes of NES Hype

To fully appreciate the NWC, you have to rewind to December 1989. Three months before the real US tournament began, Nintendo pulled off what might be the greatest marketing trick in cinema history with the release of The Wizard. While critics mauled the film, calling it a cynical exploitation, they completely missed the point. To the youth of North America, The Wizard wasn’t a commercial, it was a view of the future. The film didn’t just advertise the tournament, it created the mythology of the tournament before the US tour even existed.

Universal Pictures originally pitched the film as a video game version of Tommy, the rock opera by The Who. But under the pen of screenwriter David Chisholm, the climax evolved from a generic contest into Video Armageddon. The script laid out the blueprint for the NWC as three finalists on a massive stage, a custom cartridge with a time limit, and a screaming MC whipping the crowd into a frenzy. It primed the cultural pump, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy where consumers expected a real-world equivalent of the cinematic spectacle.

Most importantly, the film ended in a climactic competition that drove kids absolutely insane. In the movie, the finalists are shocked when the curtain rises to reveal a game no one has seen before: Super Mario Bros. 3. When the real NWC hit the road, the game had just been released in February 1990. For the millions of kids who watched Jimmy Woods hoist that trophy in theaters, the NWC wasn’t just a contest, it was a chance to step through the silver screen and live the movie.

Canada’s Hidden Role: The Beta Test

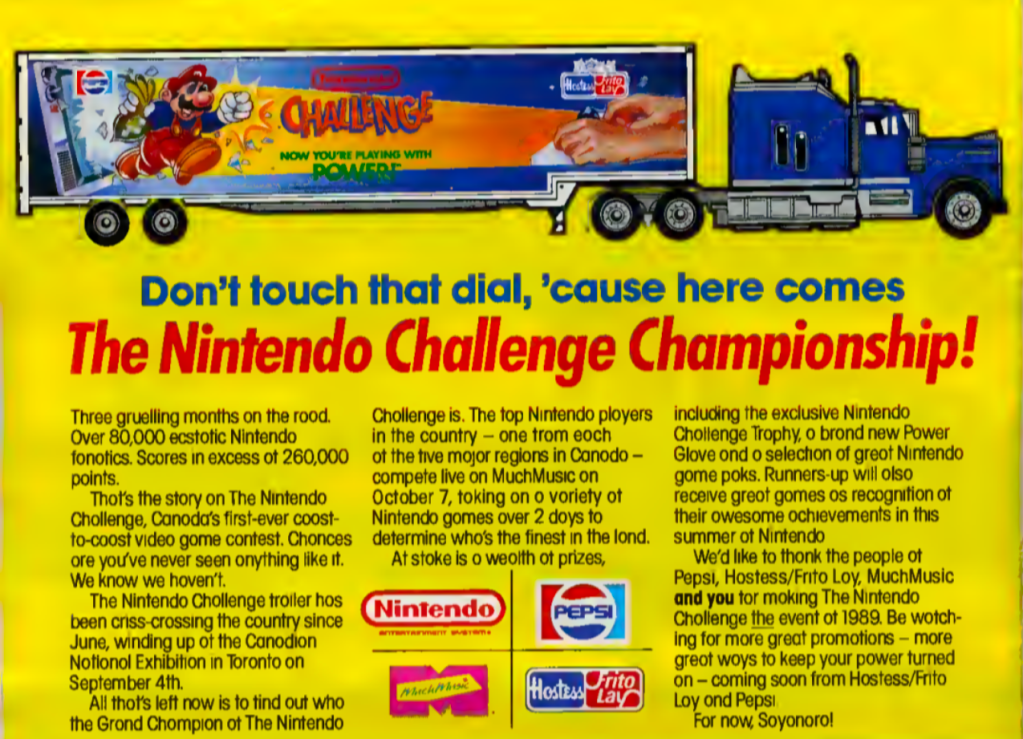

While American kids were waiting for The Wizard to hit theaters, a massive beta test was already underway across the border. The tournament concept was actually piloted in Canada starting in June 1989, nine months before the US tour began. Nintendo utilized Canada as a test market because the demographics mirrored the US, but the population was one-tenth the size, allowing them to contain the reputational risk if the concept failed.

Known as the Nintendo Challenge Championship (NCC), this Canadian tour was organized by Mattel Canada, which handled distribution rights in the region at the time. Instead of renting convention centers, the NCC used a 40-foot tractor-trailer, which unfolded into a mobile gaming stage, customized inside and out for maximum excitement! The truck traveled between malls and fairgrounds, including the Canadian National Exhibition, proving that the logistics of a touring esports event were viable before Nintendo of America committed to the massive US investment.

The response in Canada was the first indicator that esports was going to be a phenomenon. The tour saw over 80,000 ecstatic Nintendo fanatics attend the stops, with players willing to stand in line for hours for mere minutes of gameplay. Top players were scoring in excess of 260,000 points in that short window and eventually a champion was crowned, 14 year-old Huy Luong of Toronto. This successful stress test of the infrastructure provided the crucial operational data that allowed Nintendo to scale up the event for the American market the following year.

The American Tour: Heavy Metal Magnificence

When it came time to launch the US version in 1990, Nintendo of America took the lessons from Canada and supersized them. They didn’t hire a tech company, they hired rock and roll promoters. Recognizing that video games had a fanatical following similar to music, Nintendo partnered with EMCI, a marketing agency specializing in music tours. The vision was radical, a traveling rock tour for video games that would visit 29 major US cities, starting in Dallas and ending in Tampa.

This wasn’t a local science fair setup or a mall truck like the Canadian prototype. The infrastructure was massive, requiring tons of equipment to be hauled across the country in a convoy. The physical Competition Arena was designed by FM, the same design firm that created the set for the Opening Ceremonies of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics. That choice was a deliberate signal because Nintendo wasn’t just selling a toy, they were elevating gaming to an Olympic-tier event, booking massive venues like the Los Angeles Convention Center and the Fair Park Automobile Building.

Walking into one of these venues was like entering a neon-soaked theme park. The Power Walk expo floor, an expanded version of the Canadian truck concept, featured over 130 NES demo units and 200 Game Boy stations. It was a sensory bombardment where kids could play unreleased titles. On the Super Stage, Nintendo Game Counselors, usually just faceless voices on a telephone helpline, were treated like rock stars, performing gameplay feats for screaming audiences. For a generation of isolated gamers, this was a revelation, it validated their hobby as a legitimate skill and proved they were part of a massive national community.

6 Minutes and 21 Seconds of Adrenaline

At the heart of the spectacle was the competition itself, played on the legendary grey cartridge. Nintendo of America commissioned a custom-engineered piece of software that stitched three games together into a triathlon: Super Mario Bros., Rad Racer, and Tetris. The rules were rigid. Players had exactly 6 minutes and 21 seconds to rack up the highest cumulative score. But the magic lay in the meta-game. Because the final score was calculated using a multiplier, players quickly realized that playing the games normally was a recipe for failure. The strategy was counter-intuitive, exploiting the game mechanics to save precious seconds.

Competitors would blitz through a section of Super Mario Bros., where the sole objective was to collect 50 coins as fast as possible, before instantly switching to the racing game Rad Racer, where the goal was simply to complete the first track. The entire tournament hinged on reaching Tetris as quickly as possible, because its points carried a massive 25x multiplier. Ultimately, the strategy boiled down to spending the bare minimum time in the first two challenges to maximize the critical seconds for building up a massive, multiplier-fueled score in the final game.

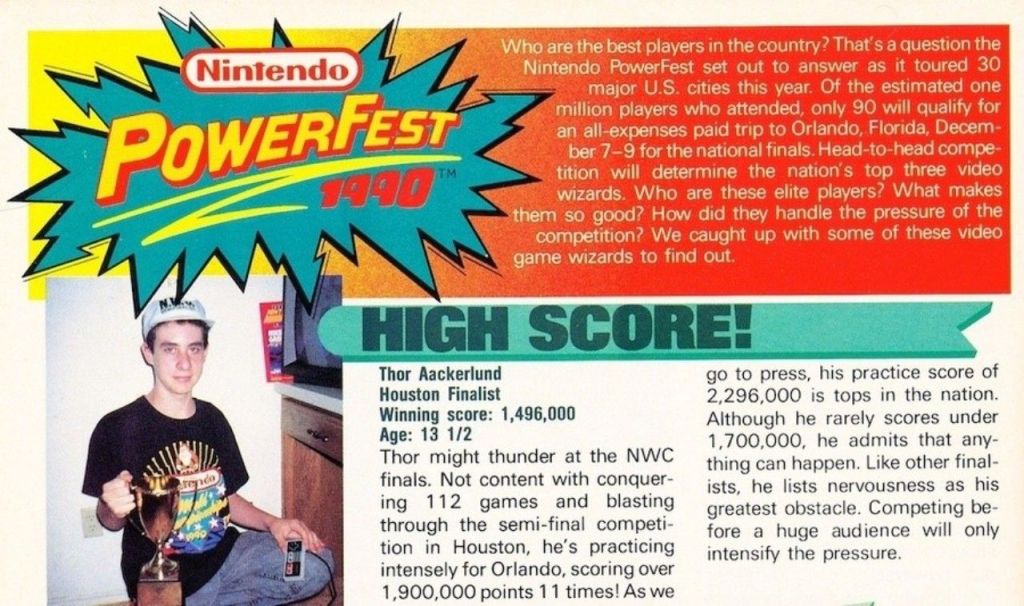

While thousands competed across three age brackets, one name rose above the rest to become the stuff of legend, Thor Aackerlund. Competitors in the 12-17 bracket were the prime demographic, and the competition was fierce. But Aackerlund, a teenager who would become the central figure of NWC lore, had a secret weapon. While other players struggled with the standard speed of the NES controller, Thor mastered a technique called hypertapping. By vibrating his thumb against the D-pad at high frequencies, he could move Tetris pieces instantly, overcoming the console’s auto-repeat limitations.

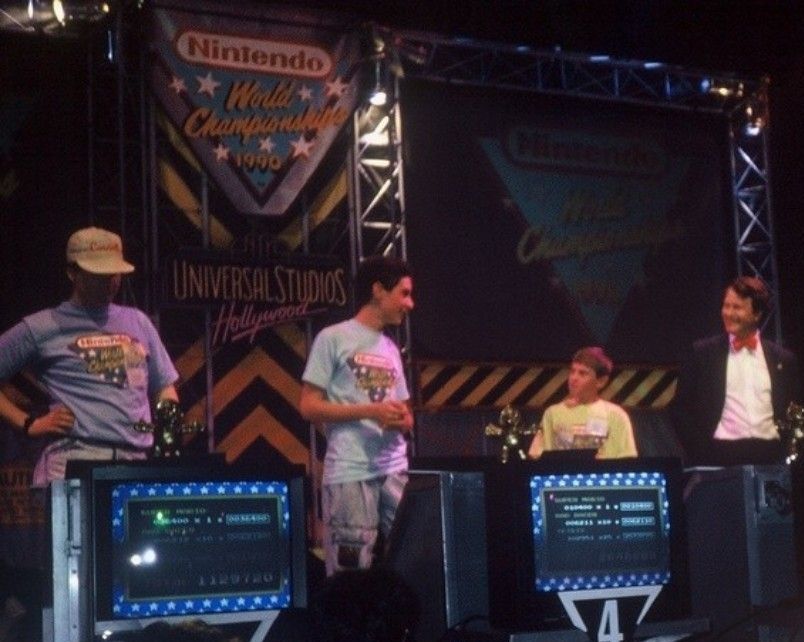

The World Finals were held in December 1990 at Universal Studios Hollywood, inside the Star Trek Theater, a poetic return to the home of The Wizard. In the finals, Thor posted a score of nearly three million points, the highest of the tournament. The prizes for the US winners reflected the massive scaling up of the event from the Canadian electronic marbles and trips. Thor’s prize package was the ultimate 1990 flex: a $10,000 US Savings Bond, a 40-inch rear-projection TV, a Gold Mario Trophy, and a 1990 Geo Metro Convertible.

The Legacy of the 1989 Experiment

The 1990 Nintendo World Championships was more than just a marketing stunt to sell Super Mario Bros. 3 and fight off the Sega Genesis. It was the Woodstock of gaming, an event that everyone claims to have been at and whose artifacts are treated with religious reverence. But history must give credit where it is due, the Nintendo Challenge Championship in Canada was the first console tournament of its kind. Initiated by Mattel Canada, it served as the critical proof-of-concept that validated the touring model before the US ever saw a single blueprint.

The tournament structure laid the architectural groundwork for the modern esports industry. The qualification rounds, the stage spectacles, the shout-casters, and the hero narratives we see today can all trace their DNA back to the Fair Park Automobile Building in Dallas in 1990 and further back to the malls of Toronto in 1989.

It was the moment Nintendo proved that a video game wasn’t just a toy. It was a sport, a lifestyle and for a few lucky kids, with fast thumbs, a way to win a convertible. The NWC didn’t just sell a console, they sold a world.

Mag Coverage

Nintendo Power #9, Nov/Dec 1989

Nintendo Power #10, Jan/Feb 1989

Nintendo Power Flash #5, Summer/Fall 1989

Leave a comment