The Hero Arrives

The late 80s offered a profound contradiction to the young gamer. In the realm of the movie theater they were immersed in a world of pure, cinematic spectacle. When a fighter jet soared across the massive screen, the sound of the afterburners landed with force. The experience was visceral, a promise of freedom and skill.

The realm of the home console, a few weeks and some saved allowance later, that towering promise was reduced to a flimsy gray cartridge. The vibrant aerial ballet was replaced by a flat, uncooperative struggle against a sky of the same three colors. The high-octane fantasy became a technical frustration, a battle not against an on-screen enemy, but against broken controls and nonsensical challenge design. The gap between a blockbuster film’s sweeping, epic vision and its rushed, lacklustre 8-bit adaptation was often full of disappointment.

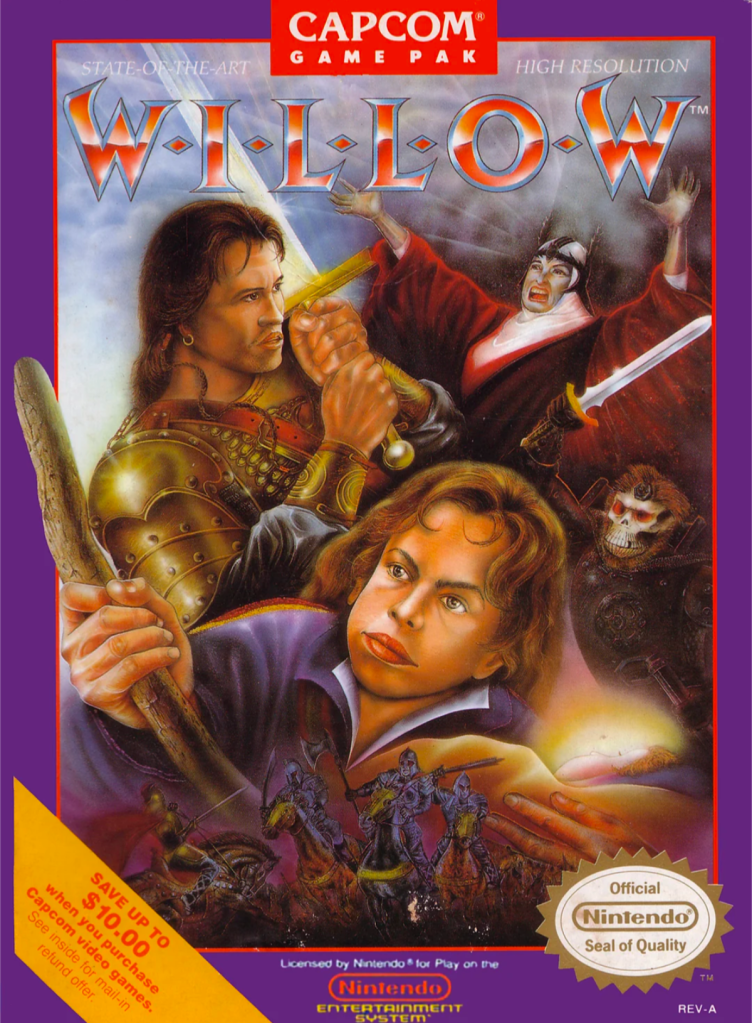

But then Willow arrived on the NES in 1989 and it did something impossible. It took a movie that critics were lukewarm about and turned it into an 8-bit action RPG masterpiece that rivaled The Legend of Zelda. This wasn’t just a quick cash grab. It was a title that defied the odds by combining the cinematic ambition of George Lucas with the design genius of Capcom.

A Galaxy Far Far Away Meets Middle Earth

The story of Willow actually began long before the film hit theaters in 1988. It started in the imagination of George Lucas during the early 70s. Before the X-Wing or the Death Star became cultural icons Lucas harbored a profound desire to translate the quintessential high fantasy journey to the silver screen. In 1972, prior to the phenomenon of Star Wars, Lucas actively sought to acquire the film rights to J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit.

He had a specific vision in mind. He wanted to adapt Tolkien’s archetype of the reluctant hero who is content in his agrarian simplicity but is thrust by destiny into a conflict of global stakes against a dark magical overlord. It was the classic hero’s journey that Lucas was obsessed with but set in a world of swords and sorcery rather than spaceships and lasers.

However the rights to Tolkien’s Middle Earth were notoriously entangled and by 1987, the rights to The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit were firmly under the control of producer Saul Zaentz, who had acquired them in 1976 and planned to produce animated adaptations. George Lucas famously attempted to secure the rights to adapt The Hobbit during this era but was stonewalled by Zaentz’s tight grip on the property. This rejection became a catalyst for creativity. Much as his inability to secure the rights to Flash Gordon drove him to synthesize his own space opera in Star Wars, the denial of The Hobbit rights forced Lucas to construct his own fantasy mythology.

You can see the DNA of Tolkien unmistakably woven into the fabric of Willow. The Nelwyns are clear surrogates for Hobbits as they live in a subterranean and pastoral society insulated from the wars of the tall people known as the Daikini. The plot revolves around a helpless chosen one who must be shepherded through perilous geography to a destination of final confrontation. Instead of a ring it is a baby but the heart of the story remains the same.

Capcom Wants to Conquer America

While Willow was finding its footing in theaters a different kind of conquest was occurring in the video game industry. Capcom was pursuing a strategy to dominate the North American home console market. Following the massive success of the NES, Japanese developers realized that the American market was not just a dumping ground for arcade ports but a lucrative ecosystem for licensed intellectual property. While western companies like LJN and Ocean Software were churning out notoriously poor quality adaptations of American films, Capcom adopted a different philosophy. They believed that a license could amplify an already great game to huge acclaim and sales.

Capcom’s strategy involved acquiring high profile Western licenses to gain an immediate foothold with American consumers who might not recognize original Japanese IPs. The acquisition of the Willow license was not merely about slapping a logo on a cartridge. It was about leveraging the Willow mythos to compete with Nintendo’s own heavy hitter The Legend of Zelda.

More Than Just a Clone

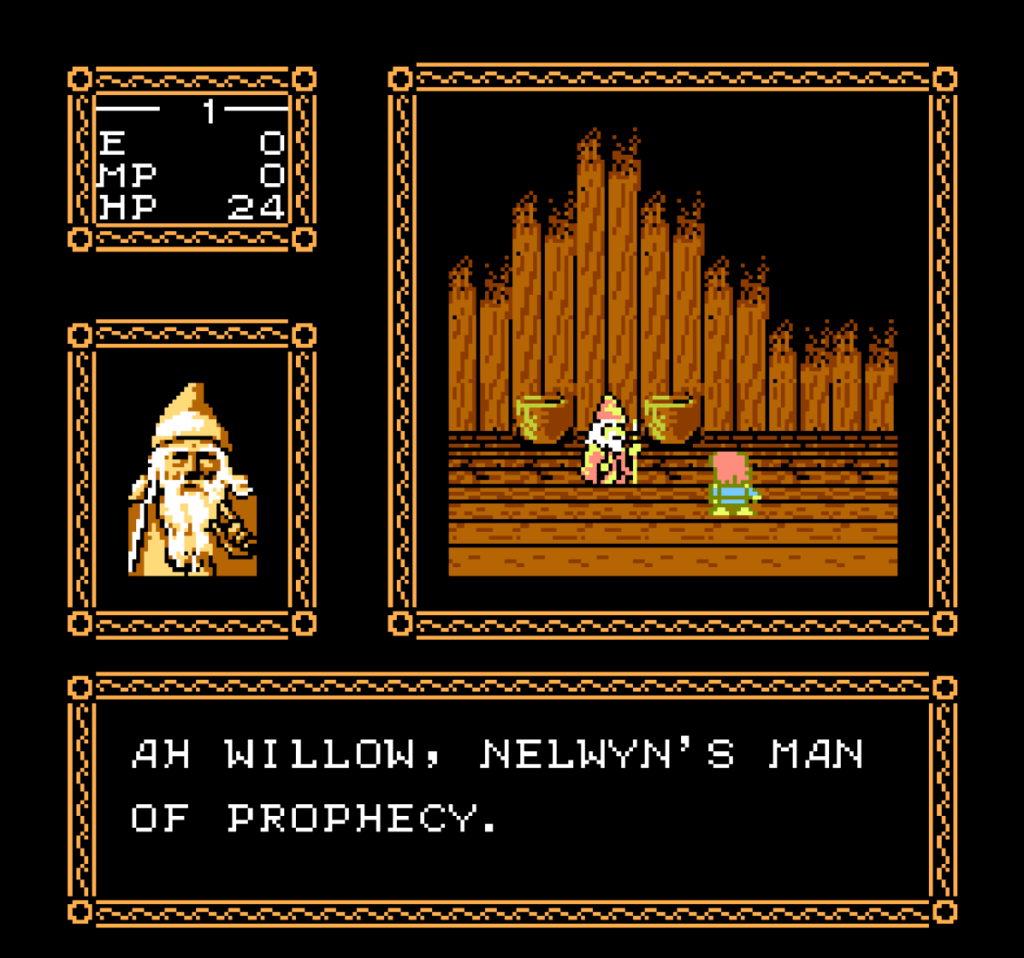

Upon its release Willow on the NES was immediately compared to Nintendo’s The Legend of Zelda. The comparison was inevitable since both games featured a top down perspective and a sword wielding hero. However labeling Willow a clone does a disservice to its distinct mechanical identity as it was actually a bridge between the action adventure of Zelda and the stat heavy mechanics of traditional RPGs like Dragon Quest.

One of the key differences that reinforces Willow’s identity as a true Action-RPG is its robust magic system. Unlike the limited utility items found in The Legend of Zelda, Willow features a dedicated MP system with a variety of selectable spells. Spells such as ‘Acorn’ (to petrify enemies) and ‘Thunder’ are essential not only for combat but also for solving puzzles and progressing through the game’s narrative. This system casts Willow as the sorcerer he was destined to become, providing a deep layer of resource management that was not present in Zelda

Additionally Willow utilizes a traditional leveling system. Defeating enemies yields Experience Points and reaching thresholds increases Willow’s Hit Points and Magic Points. This fundamentally changes the gameplay loop. In Zelda if a player cannot defeat a boss they must find a new item or improve their manual dexterity. In Willow the player has the option to grind enemies to become statistically stronger. This made the game more accessible to players who might lack arcade reflexes but possessed the patience to level up.

A Guide to the Unknown World

One of the most thrilling aspects of playing Willow on the NES was its expansion of the film’s world, creating a sprawling and dangerous geography only hinted at in the movie’s runtime and manual. The journey begins in the humble village of Nelwyn, where the game immediately establishes the stakes. Willow is not a warrior at the outset, but a farmer who must earn his heroism by visiting the High Aldwin and acquiring his first sword from Vohnkar to even begin the massive path ahead.

Then game brilliantly expands the world, immediately pushing the player out of the starting area into a sprawling and dangerous geography. The early challenges introduce a mix of pure action combat and light investigation, requiring players to interact with the environment and villagers to solve puzzles and gain access to new areas. As the journey progresses, the settings become increasingly perilous, featuring dense, monster-filled forests and massive, complex cave systems where the player must venture to collect key artifacts and defeat powerful foes. This blend of combat and investigation effectively broadens the scope of the adventure far beyond the film’s narrative.

Throughout this adventure, the game gives players a strong sense of growth and capability. New allies, such as a helpful magical creature that provides a form of fast travel, aid the adventurer in traversing the massive map. More importantly, the player continually discovers powerful equipment and artifacts that enhance their defensive and offensive abilities, reinforcing the Action RPG mechanics and making the player statistically stronger. The culmination of this long, arduous journey is a moment of triumph, where a powerful sorceress bestows upon Willow an ancient, magical artifact, signifying his transition from a humble farmer to the sorcerer he was destined to become.

The Lasting Magic

Willow serves as a testament to Capcom’s late 80s dominance and design genius. While the movie struggled to escape the shadow of Star Wars, the game successfully stepped out of the shadow of The Legend of Zelda offering a deeper and more stat driven Action RPG experience that remains highly playable today.

The film was criticized for its derivative plot. However in a video game derivative fantasy tropes like collecting swords and fighting dragons and leveling up are the foundational language of the genre. What felt cliché on screen felt comfortable and empowering on a controller. We became the hero in a way the film’s passive viewing experience couldn’t replicate. The agency allowed players to inhabit the world of Willow rather than just observe it.

Ultimately Willow on the NES represents the gold standard for licensed gaming. It proved that a tie-in did not have to be a cynical cash grab. It could be a work of art in its own right expanding the lore and offering a distinct experience from the film. In the history of the 1980s Willow is the rare instance where the console defined the legacy as much as the silver screen.

Leave a comment