Lifting the Curse of the Licensed Game

Remember that song? The one that played right after you burst through the door after school? You’d throw your bag on the floor, and flip on the humming CRT television, that blared that iconic song, Duck Tales! Woo-hoo!! The undisputed king of The Disney Afternoon. The 1987 animated series was a daily injection of pure, high-stakes adventure. We didn’t just watch Scrooge McDuck. We traveled with him, trekking through the Amazon and escaping spooky castles alongside Huey, Dewey, and Louie.

So when that iconic, colourful yellow and purple box appeared in the toy store electronics aisle, the one with Scrooge McDuck being pulled up by Launchpad McQuack, we all felt it. A mix of pure, unadulterated joy and a deep, sinking dread. We’d all been burned before. In the 1980s, video games based on movies or cartoons were almost always terrible. They were low-effort, quick cash-ins designed to exploit a popular name, not to stand on their own merits. The ghost of the infamous 1982 E.T. game, a failure so profound it helped crash the entire industry, still lingered. But this, this was Capcom. This felt different. We just didn’t know how different it would turn out to be.

A Match Made in Heaven

The true architect of the DuckTales world was the legendary writer and artist Carl Barks, whose prolific comics created the entire canon long before the animated series. He first introduced Scrooge McDuck in 1947, evolving him from a simple miser into a thrill-seeking adventurer. Critically for the NES game, Barks also created its entire cast of villains: the perpetually-foiled Beagle Boys, the sinister sorceress Magica De Spell, and Scrooge’s bitter rival Flintheart Glomgold, the game’s final antagonist. Barks also established the iconic hub of Duckburg and Scrooge’s famous Money Bin.

Following the arrival of CEO Michael Eisner in 1984, Disney was aggressively rejuvenating its properties. The Disney Afternoon was a portfolio of high-value, family-friendly IPs. The booming NES market was an obvious place to expand, but Disney had a critical problem on their hands, wanting to cash in without damaging their pristine brand with a low-quality product like E.T. Barks’ framework of a central hub, a wealthy adventurer, and episodic treasure hunts to exotic locations, was, in essence, a perfect narrative structure just waiting for a developer to adapt into a video game. In 1989, that developer would be Capcom.

By 1989, Capcom had already established itself as a premier developer for serious gamers. They were the masters behind tough-as-nails action titles like Ghosts ‘n Goblins and the legendary Mega Man. But these games, while beloved, appealed to a specific, limited demographic and Capcom wanted to expand its market access. The alliance was a stroke of genius, a symbiotic relationship that solved both problems. Disney provided Capcom with its globally recognized, A-list intellectual property. In return, Capcom provided Disney with its A-Team of development talent that had been working on the Mega Man series.

While their first collaboration, Mickey Mousecapade, was a poorly received port, DuckTales was different. This was the first major title developed internally by Capcom’s best talent. This was the real test of the synergy. The result wasn’t just a game. It was a paradigm shift that would ignite the Disney Afternoon game craze.

What Comes Down Must Bounce Up

The critical and commercial success of DuckTales was no accident. It was the direct result of a prestige-level, hybrid US-Japan development team. Capcom assigned its absolute top-tier talent. The producer was Tokuro Fujiwara, a creative force who had created Ghosts ‘n Goblins and produced the seminal Mega Man 2. The designer was Keiji Inafune, a key artist for Mega Man, whose visual style defined that series and rounding out the team would be composer Hiroshige Tonomura. But they weren’t alone. On the American side, Disney producers like Darlene Waddington and David Mullich served as brand protectors. Their mandate was to keep the game on-track, Disney-wise. Providing official line art, cleaning up dialogue, and ensuring the characters did not commit any un-Disneyesque acts of violence.

This created a unique creative paradox. Capcom’s A-Team had a design language built on shooting, explosions and destruction. Disney’s team explicitly forbade this. So how could you possibly make a Mega Man-style action game without violence? The answer to that question became one of the most iconic mechanics in video game history: the pogo-jump.

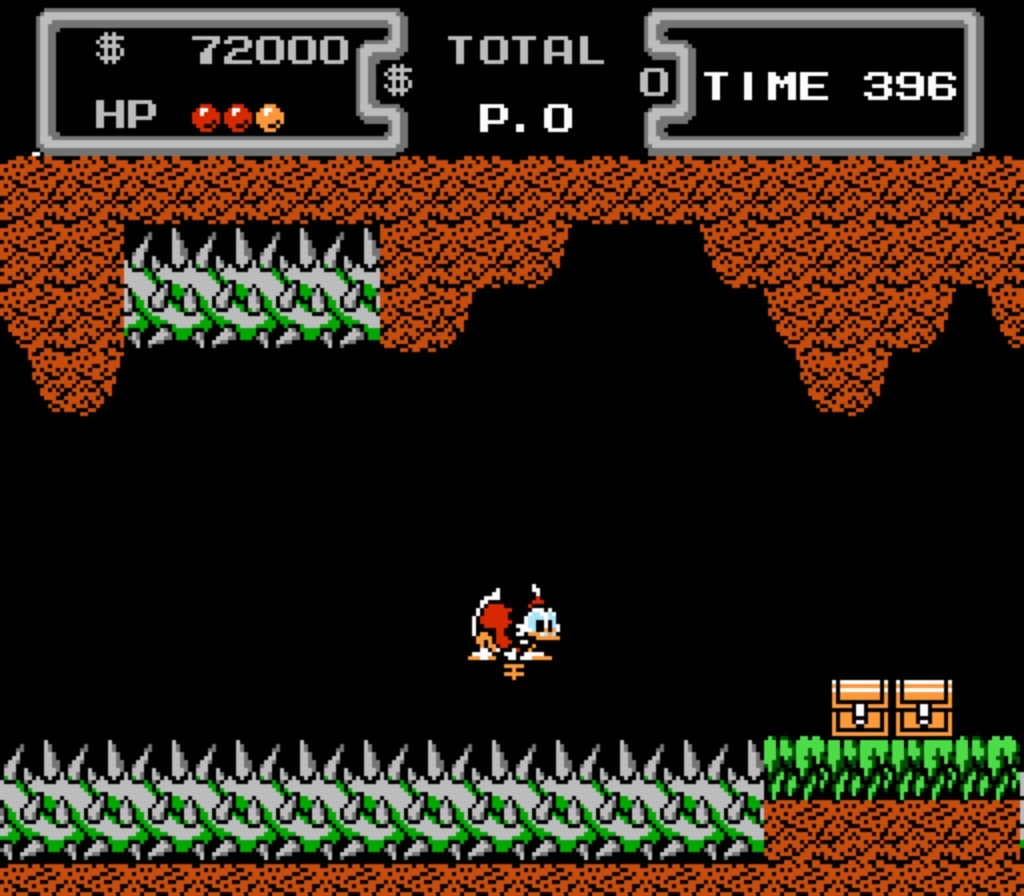

This one inspired addition was the game’s entire soul. Activated by holding down and pressing the B button in mid-air, Scrooge’s cane bounce was a masterpiece of unified design that served three critical functions at once. It was his primary Combat tool, his ability to traverse the hazards found throughout the levels while also allowing him to solve the varied environmental puzzles he faced on his adventure. This pogo-jump was the direct solution to Disney’s non-violence mandate. Mega Man’s enemies explode. Scrooge’s enemies, when bonked, just bounce off-screen, presumably to a safe landing. It was perfectly brand-safe. While Zelda II had a similar downward thrust, DuckTales was the game that popularized it and built its entire philosophy around it.

This mechanic was then paired with a brilliant level structure. The Mega Man influence was easy to see. The game featured a non-linear, open-ended level select screen. You could choose to tackle The Amazon, Transylvania, African Mines, The Himalayas, or The Moon in any order you wished. But DuckTales iterated on this formula by adding internal non-linearity. These stages weren’t simple A-to-B obstacle courses. They were maze levels with alternate routes, hidden rooms, and secrets that rewarded your freedom to explore.

This design introduced a light Metroidvania element of gated progression, something truly advanced for the time. For example, to acquire the main treasure in the African Mines, you first had to travel to the Transylvania level, find a hidden key and then return to the Mines to unlock the path forward. This simple, interlocking objective system was a notable evolution of the more straightforward Mega Man formula.

This is what made the game a masterpiece. The pogo was the engine of exploration and was the tool that let you discover the levels’ secrets, break open chests and access the hidden vertical paths. Capcom took the Mega Man structure but built a new, wholesome experience inside it.

A Timeless 8-Bit Anthem

And then, there was the music. Alongside its flawless design, DuckTales is legendary for its soundtrack. The score was composed by Hiroshige Tonomura. And while his themes for the Amazon and Transylvania are fondly remembered, the Moon theme stood above the rest. This music for the game’s final, off-world level is frequently cited as one of the greatest pieces of 8-bit music ever written. It’s an uptempo, space-age composition that feels significantly more complex and original than the game’s other tracks.

The track’s cultural impact has been immense, inspiring countless orchestral, metal, and acapella renditions. Its legacy is so powerful it willed its own canonization into existence. The creators of the 2017 DuckTales reboot, who had grown up playing the NES game, were fully aware of the song’s cult status. In a remarkable tribute, they officially absorbed the 8-bit melody into the DuckTales lore. It was reimagined as a lullaby sung by the long-lost mother of the nephews, Della Duck, who sang it to her ducklings when they first hatched.

The Richest Duck in the World

DuckTales wasn’t just a critical darling. It was a commercial juggernaut that validated the entire Disney-Capcom strategy. Released in North America in October 1989, the NES version sold over a million copies worldwide. The 1990 Game Boy port was also a smash hit, selling another million units. This combined success made DuckTales Capcom’s best-selling title for the platform at the time, even outselling the company’s own flagship Mega Man series.

This is the ultimate legacy of DuckTales. It remains the definitive benchmark for a licensed video game. It inverted the paradigm of the 1980s. The old, failed model was to use a popular IP to sell a mediocre game. DuckTales proved a new, revolutionary model of using a spectacular game to elevate a popular IP. Its quality was not just good for a licensed game. It was one of the best games on the console, period. The fact that it became Capcom’s best-selling NES title proves that its quality was the primary driver of its success, not just its license. For a generation of kids, the game became as central to the memory of DuckTales as the show itself.

Its success greenlit a golden age of beloved Capcom-Disney collaborations, including Chip ‘n Dale Rescue Rangers, TaleSpin all the way up to SNES games like Aladdin. DuckTales shattered the licensed-game curse and established a new gold standard. It was the definitive proof that investing A-Team talent in a licensed property was a massively profitable strategy, and that a game based on a cartoon could be a timeless, best-in-class classic.

Leave a comment