Forged in the Arcades for Gamers by Gamers

Back in the pre-internet era of the late 80s, the video game landscape was a digital wild west, a burgeoning frontier recovering from the industry crash of 1983. This left you in a tough spot. When you only got one shot—that single game for Christmas or a birthday—then you might be stuck with a devastatingly bad choice for the whole year. How did you find the best games? How did you know which adventures were truly worth that one precious pick? Where could you find the cheat codes to let you finish your latest cartridge so you could beg your mom for a new one? While Nintendo’s own wildly successful Nintendo Power magazine existed, it was largely a promotional tool designed to hype all games and all of its systems, regardless of their quality.

You needed a secret weapon, an independent voice in a media landscape often seen as beholden to advertisers and platform manufacturers. You needed a guide through this jungle of bad games and that guide was Electronic Gaming Monthly. Forged not in a corporate boardroom but in the heart of the arcade, it was a magazine made by total gaming fanatics, for total gaming fanatics. This is the origin story of how a high-school dropout arcade wizard, a legendary crew of reviewers, and an unwavering belief in honest journalism created the ultimate gaming bible for an entire generation.

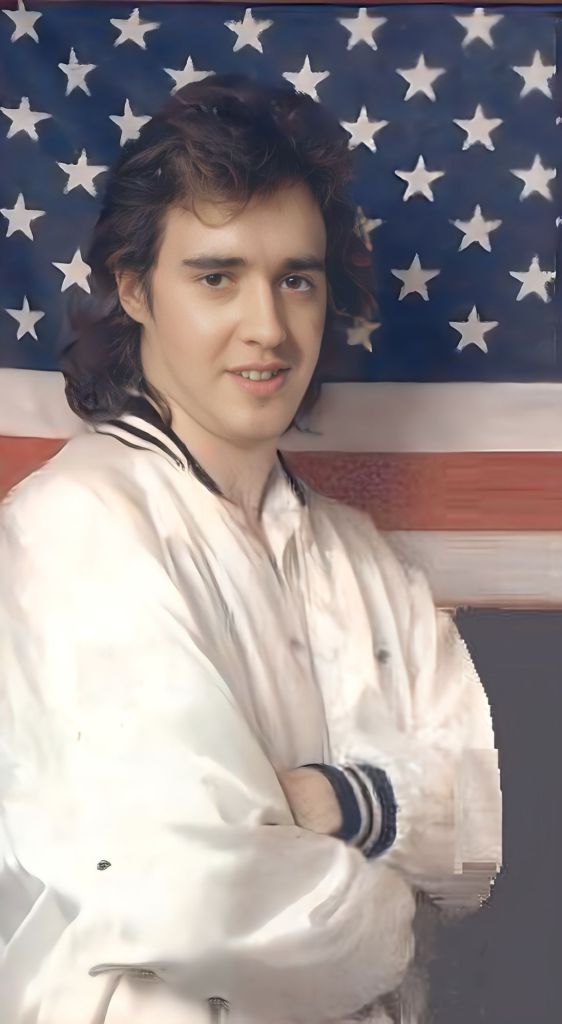

The First Player – Steve Harris, Arcade Wizard

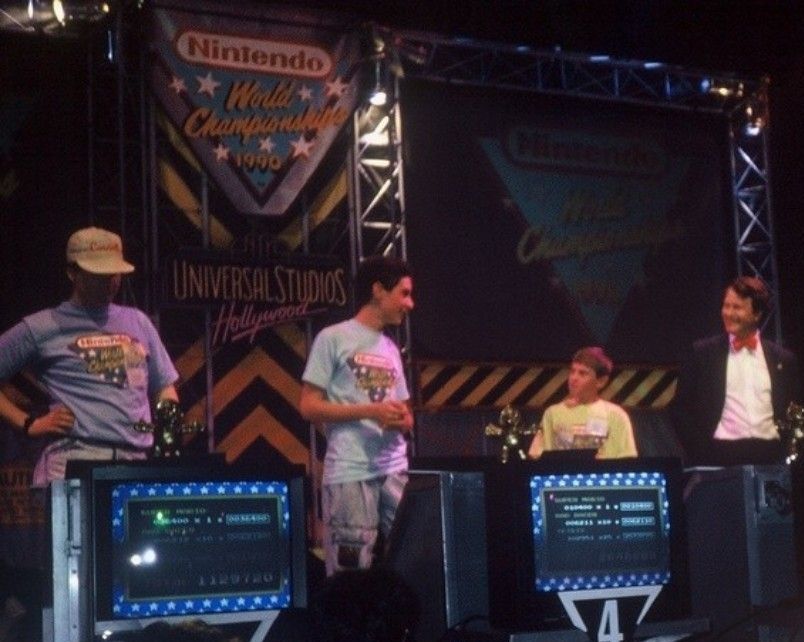

EGM’s origin story begins with Steve Harris, a product of the Golden Age of Arcade Gaming. This pivotal era, saw titles like Space Invaders and Pac-Man transform arcades into vibrant social hubs and establish video games as a dominant entertainment medium. It was in this fervent environment that Harris, a high-school dropout and video game enthusiast, cultivated his passion. For him, video games weren’t just a hobby, they were his life, leading him to become a key member of the original U.S. National Video Game Team, a traveling squad of professional gamers initiated by the Twin Galaxies arcade to conduct game demonstrations across the country. To the faithful who gathered at arcades, these joystick masters were rock stars.

Harris wasn’t just playing games, he was an elite competitor, officially recognized as one of the most talented arcade players of the 1980s. His prowess is evidenced by several #1 ranked scores verified by the legendary Twin Galaxies arcade itself, including Popeye and Congo Bongo. His formal involvement with the scene deepened in 1984 when he took on the responsibility of maintaining Twin Galaxies’ national high-score board. This role soon expanded beyond simple scorekeeping, as he began directing projects for the National Video Game Team and organizing his own arcade tournaments.

His influence grew further within the team’s leadership. In the period after 1986, Harris began to manage the team’s business and promotional activities. This experience gave him insight not just into playing games, but into the business and community surrounding them. This complete immersion—as a top-tier player, an official scorekeeper, a tournament organizer, and a team manager—provided him with an unmatched, firsthand knowledge of the player community and its interests. This deep, authentic connection would profoundly shape his future editorial endeavors and become the secret sauce that made EGM unstoppable.

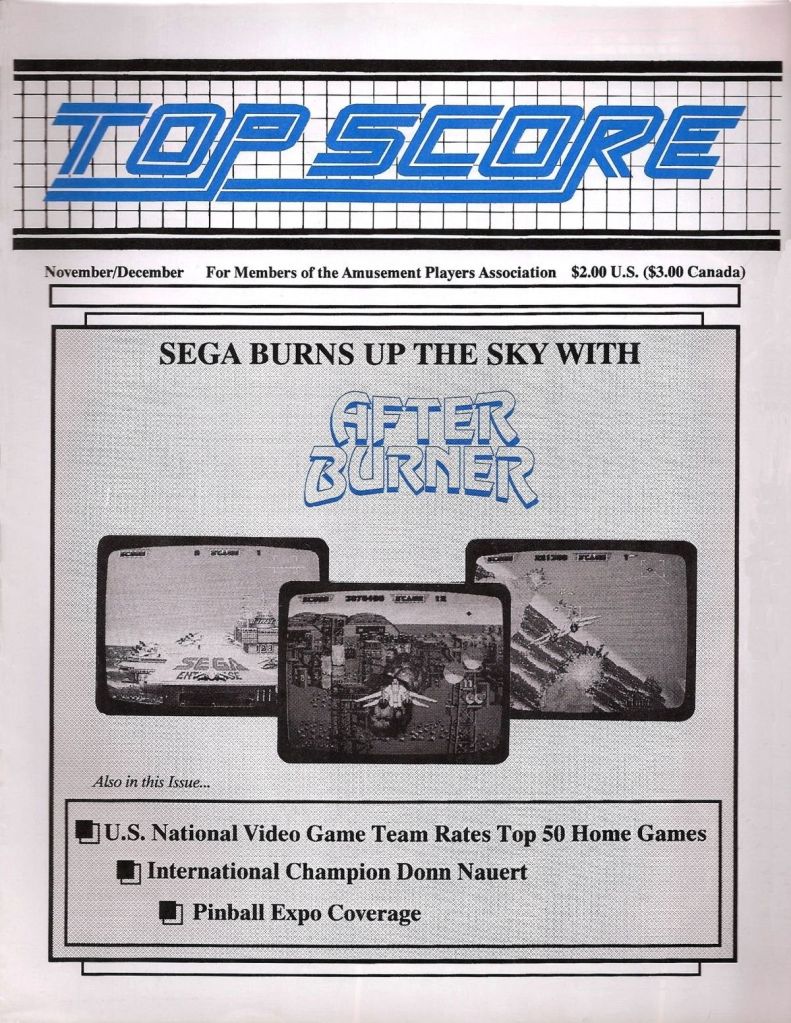

Top Score and Electronic Game Player

Harris first entered into the publishing world with a plucky fanzine he self-published called the Top Score Newsletter, starting in 1986. It was an extension of his National Videogame Team activities, a raw, passionate publication for arcade and home players that was all about high scores, strategy sessions, and player profiles. It was a signal flare, a small voice for a community that was about to explode.

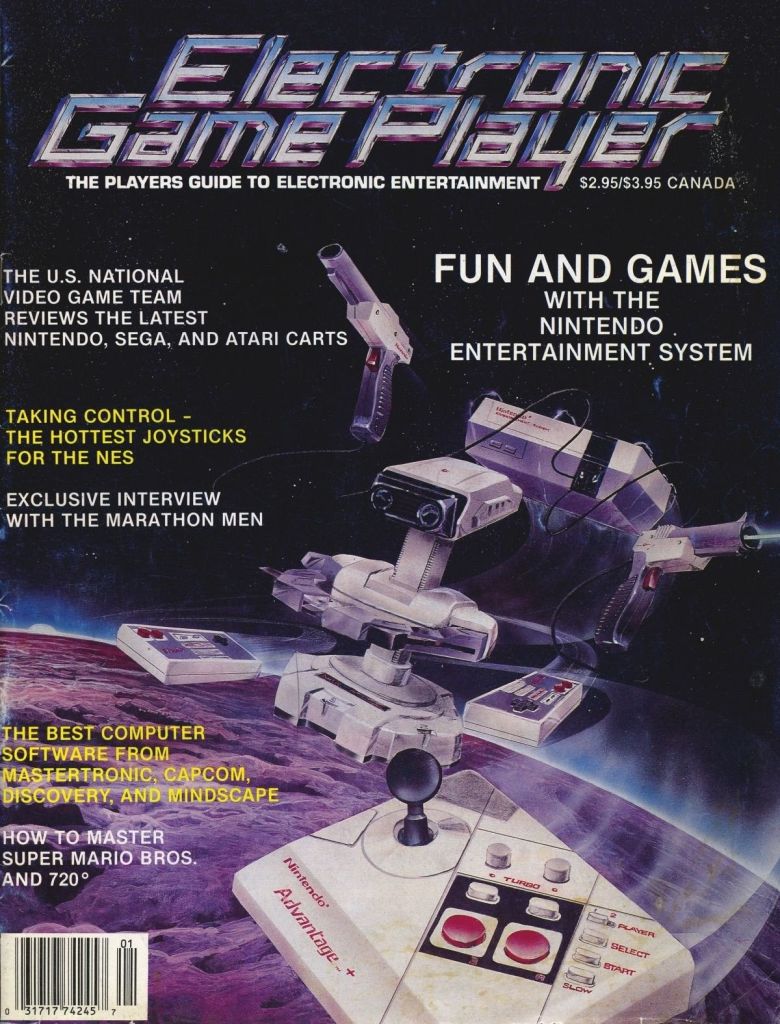

The Top Score Newsletter ran from the fall of 1986 until December 1987. It didn’t so much end as it evolved when Harris partnered with his friend Jeffrey Peters to hold the 1987 Video Game Masters Tournament and used the proceeds to launch a full-blown magazine: Electronic Game Player. Debuting in early 1988 with Harris as its editor, EGP was the direct dress rehearsal for EGM. It had console and arcade coverage, strategies, and even the first appearance of the legendary industry gossip columnist, Quartermann. The vision was there. Harris knew the world was ready for a real gamer’s magazine. But then EGP died after only four issues.

The problem wasn’t the content—it was fantastic. The problem was a monstrous barrier to entry: the national magazine distributors. These companies were terrified of video game magazines after a bunch of them went belly-up during the 1983 crash. They refused to take a chance on EGP, meaning you could barely find it anywhere outside the West Coast. It was a brutal, heartbreaking lesson: a killer magazine means nothing if it can’t get onto the store racks. For Harris and his dream, the screen faded to black.

Or did it? Just when it seemed like our hero’s luck had run out, the phone rang. On the line was Harvey Wasserman, a Chicago-based distributor who saw the magic everyone else had missed. Connected to Harris through an acquaintance, he didn’t just see a failed magazine, he saw a brilliant concept that needed a boost. So he dropped an initial $70,000 in funding and, most importantly, made the crucial promise to handle the distribution himself. It was the break Harris desperately needed, the game was back on.

The Launch of EGM

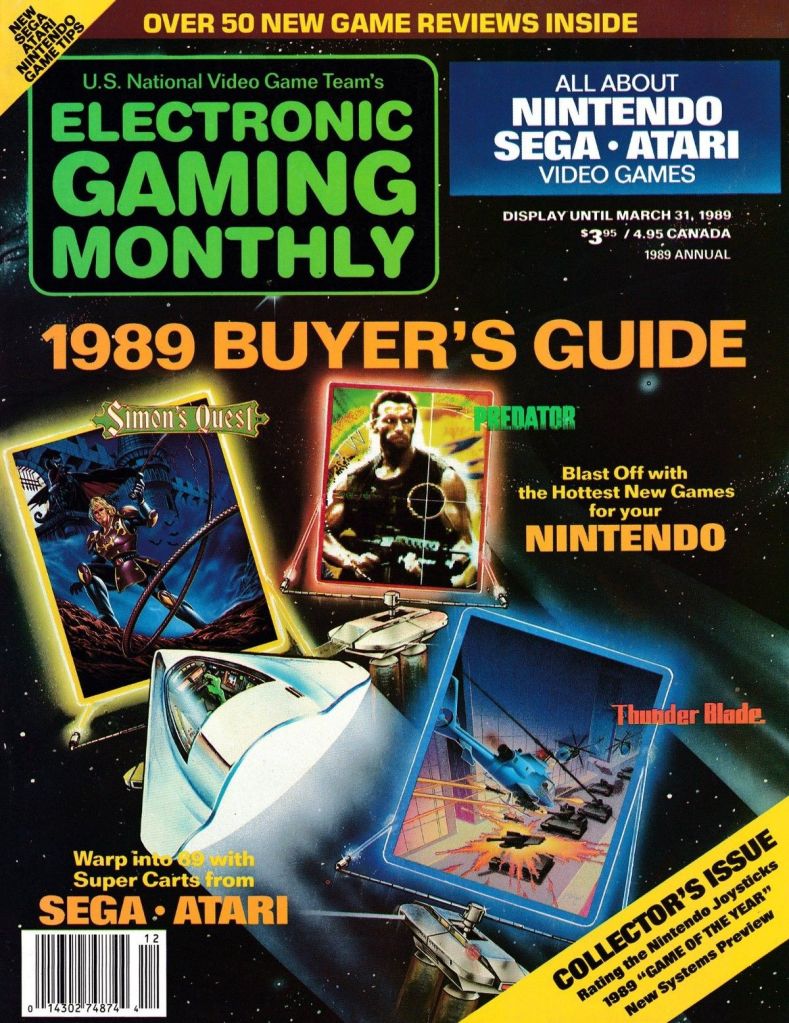

With that lifeline secured, Wasserman then orchestrated a game-changing play. He secured a rare deal with the Kay-Bee toy store chain, getting a $100,000 advance for Harris in exchange for 60,000 copies of the magazine’s second issue. In an unheard-of move, Kay-Bee’s executives—anticipating a massive video game boom—paid for every single copy upfront. This pivotal deal gave Harris the resources and security to pour everything he had into the project, working around the clock to perfect the magazine he had always dreamed of creating.

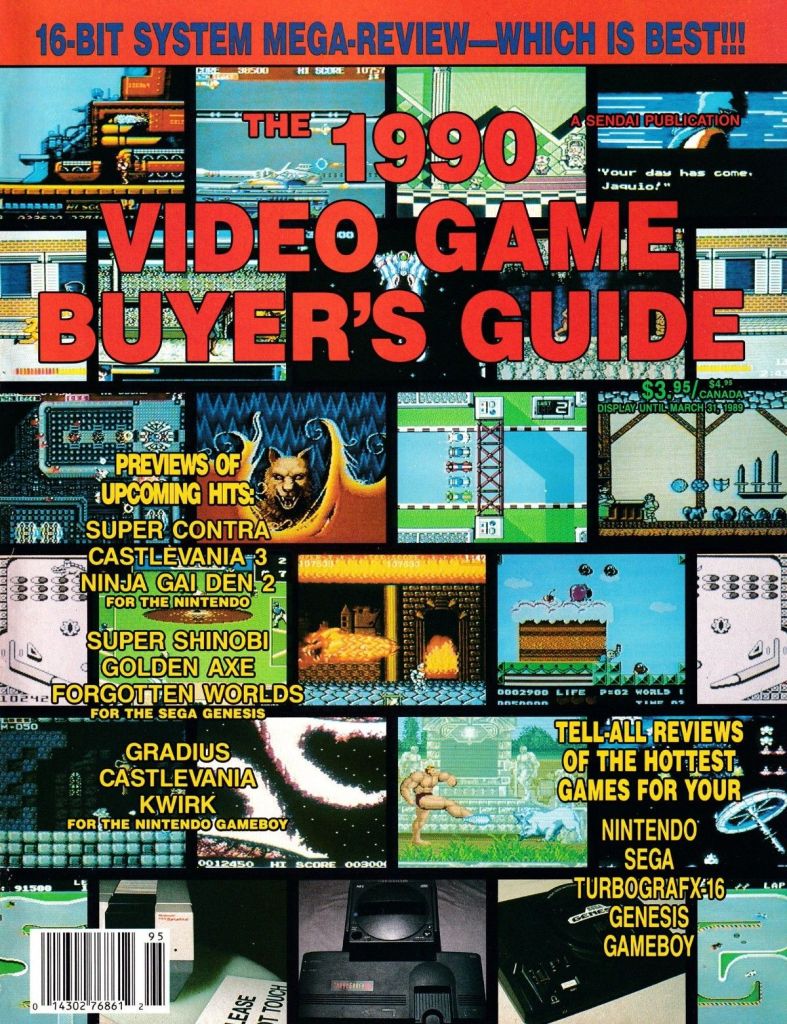

With this new life, Harris created a new publishing company, naming it Sendai Publishing because it sounded Japanese enough to impress the tech heads. Instead of jumping straight into a monthly subscription, they pulled a genius move. They launched a special, one-shot 1989 Preview Guide to test the waters and it paid back in dividends, far exceeding anyone’s expectations. The guide sold a whopping 107,000 copies, with a huge chunk of those—60,000 units—flying off the shelves at Kay-Bee toy stores. The world wasn’t just ready, it was starving.

The success was undeniable. It was time. The first official issue of Electronic Gaming Monthly, Volume 1, Number 1, hit the scene with a May/June 1989 cover date. Steve Harris was back in the editor’s chair, and the “Insert Coin” editorial—a signature from EGP—was right there on the first page, signaling that the original vision was back and stronger than ever. EGM had officially been born.

The Secret Weapons of EGM

EGM didn’t just exist, it ruled. From its very first year, it had an arsenal of secret weapons that no other magazine could touch. These were the features that had you ripping the plastic off the second it arrived.

The Review Crew: Four Times the Fun

This was the game-changer. Starting with issue #2, EGM unleashed the Review Crew. Forget one boring review from some faceless writer. EGM gave you four. A whole panel of different reviewers would play and score each game, and their unfiltered opinions would be printed side-by-side. It was revolutionary for a U.S. magazine. It meant you got multiple perspectives, sparking countless arguments with your friends about which reviewer you trusted most. It gave the reviews an unmatched sense of honesty and authority.

Quartermann: The All-Knowing Oracle of Rumor

Long before internet leakers, there was the mysterious Quartermann. This enigmatic gossip columnist, a holdover from EGP, was the source of the juiciest, most tantalizing industry rumors imaginable. Was Sega secretly working on a CD-ROM add-on? Was a new Street Fighter character in the works? Flipping to the Gaming Gossip column was your first move. Were the rumors always true? Who cares! It was pure, unfiltered fun that made you feel like you had a spy on the inside.

Your Japanese Passport

EGM didn’t just tell you about games coming to America, it opened a portal to the incredible, often bizarre world of Japanese gaming. With sections like the 16-Bit Sizzler, it showed you the future, covering powerhouse hardware like the TurboGrafx-16 and Sega Genesis long before they were common household names. This inside track on imports and upcoming tech made you feel like the smartest gamer on the block.

Conquering the Market

Armed with its incredible content, EGM was ready to take on the American market. The magazine was an instant hit, becoming profitable by the end of its very first year in 1989—a stunning victory compared to EGP’s struggle. Proving EGM’s financial viability was paramount to overcoming the trepidation of the big magazine publishers lingering from the video game crash.

EGM’s rapid success gave Harvey Wasserman, the ammo he needed. To convince a major distributor like Time Warner, Wasserman could now present EGM not as a risky idea, but as a proven, profitable product. He leveraged the concrete sales figures from the initial buyer’s guide—which sold 107,000 copies—and the magazine’s swift achievement of profitability as undeniable evidence of a pent-up market demand. For Time Warner, this reduced the risk that had scared off other distributors. EGM was a product with demonstrated financial viability and a clear audience, making it an attractive and logical addition to their portfolio, especially with the concurrent success of Nintendo Power having already demonstrated a clear market appetite for gaming magazines.

The Legacy of EGM

The story of EGM’s birth is more than just business, it’s a tale of passion, resilience, and knowing your audience. It succeeded because Steve Harris learned from his EGP failure and came back with a better strategy. He built a magazine on a simple, powerful philosophy: be honest, be first, and write for the reader.

EGM’s launch in 1989 was a cultural explosion. The combination of the Review Crew’s credibility, Quartermann’s irresistible gossip, and a genuine for gamers, by gamers attitude created a product that felt essential. It didn’t just review games, it shaped the conversation and built a community. It was, and always will be, a legendary part of video game history, an invaluable guide created off the passion of one person, Steve Harris.

Leave a comment