Moonlit Duel: The Dragon Sword Falls

The wind howls, a mournful sound carrying across the moon-drenched landscape where two shadowy figures, dueling ninjas, lock gazes in the pale light. For a fleeting moment, they are but silhouettes against the night sky, until a glint of steel in the moonlight signals the brutal end of their contest. Ken Hayabusa, esteemed head of his clan and generational guardian of the sacred Dragon Sword, is defeated.

His son, Ryu, soon learns of this crushing loss, a discovery that sets in motion a chain of events shrouded in mystery and peril. A final, cryptic message whispered, a plea to journey to America, and the legendary Dragon Sword passed from father to son. Clasping the hilt, Ryu felt not just cold steel, but the burning heat of unanswered questions and a burgeoning thirst for vengeance. Who were these shadowy figures strong enough to best his father? What dark purpose lay behind this tragedy? With his father’s last words echoing in his mind, Ryu Hayabusa turned his gaze westward, his solitary quest for truth and retribution ignited in the aftermath of the duel.

Press Start for Pain

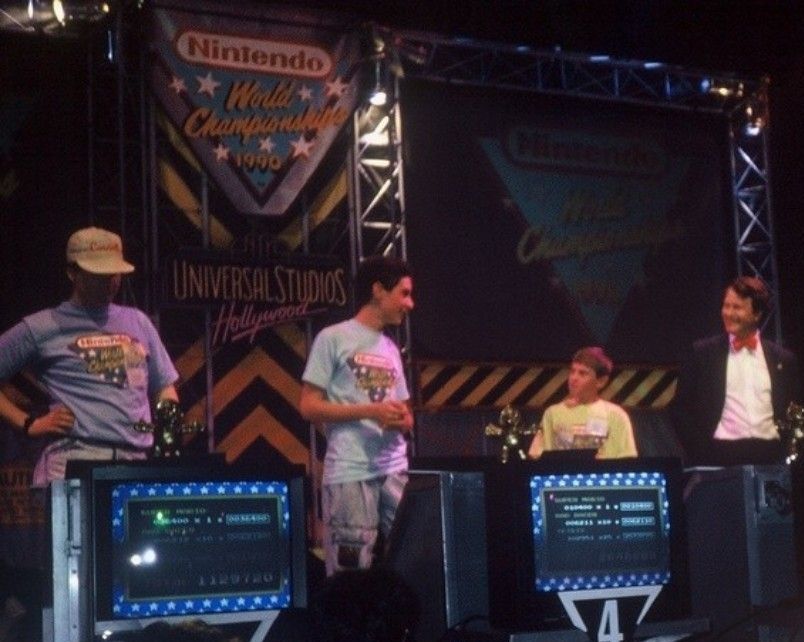

In 1989, Tecmo’s legendary game Ninja Gaiden arrived like a perfectly aimed shuriken, embedding itself deep into the very fabric of 8-bit NES landscape of the time. For many of us, Ninja Gaiden wasn’t just another game, it was a rite of passage. It was a test of skill, patience, and occasionally, the structural integrity of our controllers. But beyond the legendary difficulty, it was a masterpiece of action, atmosphere, and surprisingly cinematic storytelling that pushed the humble NES further than many thought possible.

For those who braved its perilous stages, Ninja Gaiden carved out a unique space in their gaming memories, becoming the subject of shared war stories and playground legends. It was a game that demanded you learn its rhythms, anticipate its cruelties, and celebrate every hard-won inch of progress. The thrill of finally conquering a brutal boss after countless attempts, or reaching a new cinematic cutscene that unveiled another piece of Ryu’s compelling story, provided a powerful sense of accomplishment that few other titles could match, fostering a mix of respect, frustration, and an undeniable addiction to its sharp-edged charm.

Enter the Ninja: A Perfect Storm of Pop Culture

You have to remember the cultural climate Ninja Gaiden landed in. The late 1980s weren’t just about big hair and neon, America was utterly obsessed with ninjas. These silent, black-clad warriors were everywhere. This fascination wasn’t born overnight. It simmered through the 70s martial arts craze kicked off by Bruce Lee and got a boost from Frank Miller’s gritty ninja comic, Ronin. But the real ignition point came from Cannon Films and their glorious B-movie ninja trilogy.

Films like Enter the Ninja, Revenge of the Ninja, and Ninja III: The Domination introduced the West to the stoic, deadly prowess of Sho Kosugi, who instantly became the face of the ninja boom. These movies, often cheesy but always action-packed, cemented the ninja archetype – the stealthy assassin with mystical skills and cool gadgets.

By 1989, this ninja craze was at its absolute peak, thanks in no small part to four amphibious residents of the New York sewer system. The Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles animated series had exploded onto the scene. Suddenly, “Turtlemania” was everywhere – toys, cereal, and yes, even an NES game. Ninjas, mutated or otherwise, were firmly lodged in the pop culture consciousness. Tecmo couldn’t have picked a better time to unleash Ryu Hayabusa upon an unsuspecting North American audience. The stage was perfectly set for a high-quality ninja action game on the dominant console of the era.

Yoshizawa’s Blueprint: Speed, Precision and Wall Jumping

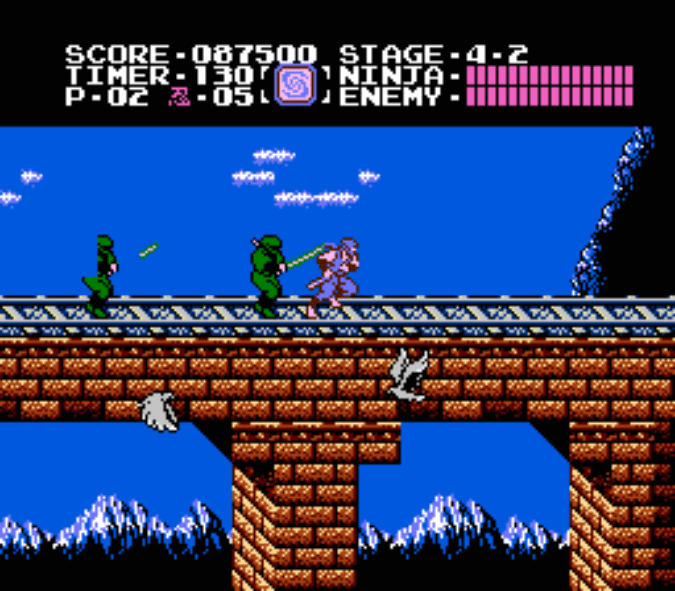

Ninja Gaiden for the NES was the brainchild of director Hideo Yoshizawa. Yoshizawa envisioned something different, something that captured the essence of being a ninja – speed, agility, and precision. He drew inspiration from platforming giants like Mario and Castlevania but infused it with a unique, fast-paced identity. His team crafted Ryu Hayabusa, not as a generic brawler, but as a nimble warrior able to jump off walls was revolutionary.

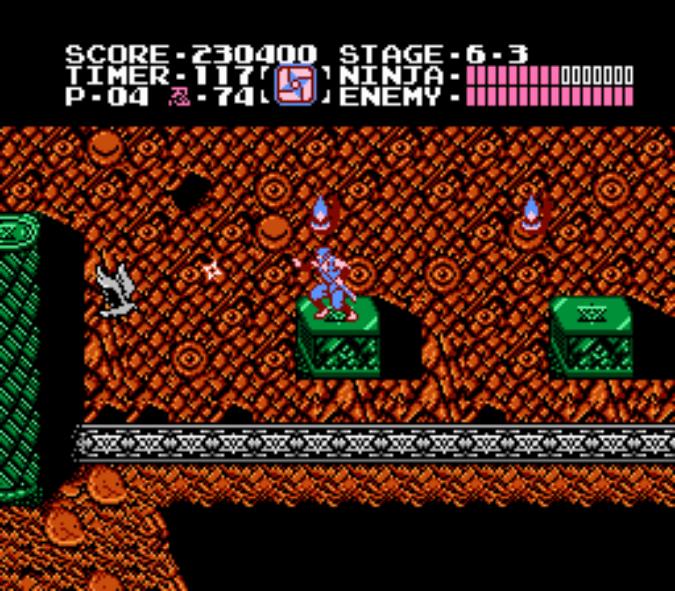

Ninja Gaiden was hard. Brutally, soul-crushingly, controller-throwingly hard. It became a poster child for Nintendo Hard, a term whispered with a mix of reverence and PTSD by NES veterans. Why was it so tough? First, there was the infamous knockback. Get hit by anything – a stray bullet, a swooping bird, a charging thug – and Ryu would recoil violently backward. Given that Tecmo seemingly loved placing enemies near ledges and bottomless pits, this often meant instant, infuriating death. Your life bar sometimes felt like a cruel joke, the real enemy was gravity, weaponized by pixelated foes.

Then there were the enemies themselves. They weren’t content to just attack you, they respawned. Instantly. Move the screen edge just a pixel too far and poof, that swordsman you just dispatched was back for more. This punished hesitation and forced a relentless forward momentum, turning levels into high-speed obstacle courses demanding memorization and split-second timing. Adding insult to injury, Ryu had virtually no invincibility frames after taking a hit. You could be juggled between enemies or repeatedly damaged by the same hazard in rapid succession.

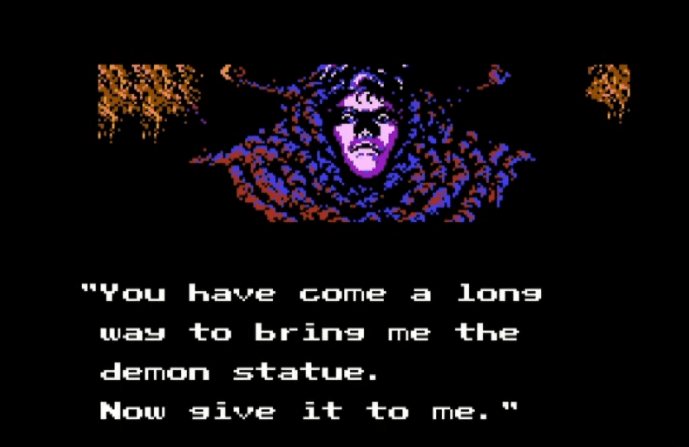

And the bosses? They were formidable tests of pattern recognition and resource management. But the real kicker was the penalty for failure. Dying often meant restarting the entire Act, not just the boss fight. This culminated in the legendary final boss gauntlet. Facing Jaquio, the resurrected Demon Statue, and the monstrous Jashin demanded near perfection. One slip-up against any of the three forms, and you weren’t just restarting the fight – you were sent all the way back to the beginning of Act 6-1!

Yet, somehow, this difficulty was part of the magic. It demanded mastery. Every cleared screen, every defeated boss felt like a monumental victory, earned through sweat, tears, and maybe a few choice words. Ryu’s core abilities – the responsive jump, the satisfying slash of the Dragon Sword, the crucial sub-weapons like the Windmill Shuriken or the Art of the Fire Wheel – felt precise and powerful. Overcoming the odds, mastering the rhythm Yoshizawa intended, was immensely satisfying.

Beyond Pixels: A Cinematic Revolution on the NES

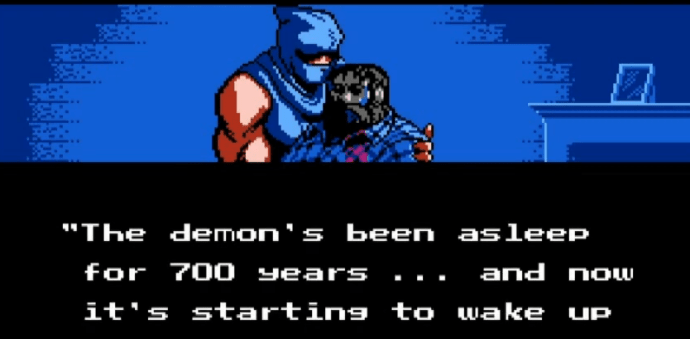

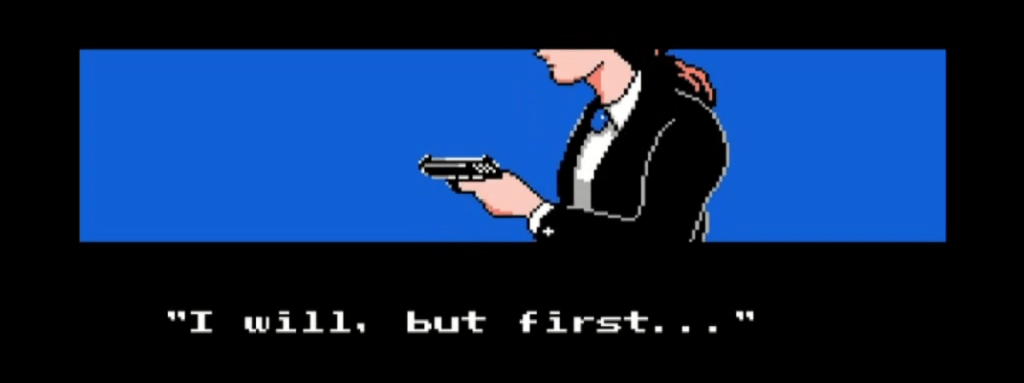

While the gameplay hooked you, Ninja Gaiden’s storytelling elevated it to another level. Tecmo introduced “Cinema Display” – over 20 minutes of cutscenes integrated seamlessly between the action stages. This was groundbreaking for an 8-bit action game. Spearheaded by Masato Kato, these sequences used still images, dynamic framing, close-ups, and scrolling text, mimicking the feel of manga and anime.

Suddenly, we weren’t just controlling a ninja sprite, we were following Ryu Hayabusa’s quest for revenge after witnessing his father’s apparent death. We met the mysterious CIA agent Irene Lew, uncovered a convoluted plot involving ancient Demon Statues and dark cults, and felt the sting of betrayal. The story wasn’t Shakespeare, but it had vibes. It felt epic, transforming the NES from a simple game machine into a “thrilling storytelling tool.” For many kids in 1989, it was like playing through a 45-minute anime OVA, providing context and motivation that few action games offered at the time.

The dramatic “What the…?!” moments and the surprisingly complex plot twists kept players invested, eager to see what happened next after surviving each grueling stage. Nintendo Power even recognized the game’s “Best Ending” in its 1989 awards, a testament to the narrative’s impact.

The Sound of Shadows: An Iconic Chiptune Score

No discussion of Ninja Gaiden is complete without mentioning its incredible soundtrack. Composed primarily by the legendary Keiji Yamagishi, the music was as integral to the experience as the gameplay itself. Yamagishi masterfully wrangled the NES’s limited sound chip, using techniques like sampled percussion and clever effects to create tracks that were energetic, catchy, and perfectly matched the on-screen action.

The driving stage themes pulsed with urgency, pushing you forward through waves of enemies. The boss music was tense and dramatic, amplifying the stakes of each encounter. Even the melancholic “Requiem” track added unexpected emotional depth.

Short, repetitive loops underscored the relentless pace, drilling themselves into your brain until they became synonymous with ninja action. It’s a soundtrack that still resonates today, instantly recognizable and beloved by retro gaming audiophiles.

Legacy of the Dragon Ninja

More than just a commercial hit, Ninja Gaiden left an indelible mark. It introduced Ryu Hayabusa, one of gaming’s most iconic ninja heroes. Its demanding, skill-based gameplay became a benchmark, and its “Cinema Display” proved that deep narratives could thrive even within the constraints of 8-bit action games, influencing countless titles that followed. It perfectly captured the zeitgeist of the 80s ninja craze while pushing the boundaries of NES game design.

So, the next time you feel nostalgic for the 8-bit era, remember Ninja Gaiden. Remember the frustration of that knockback, the terror of Act 6-2, the triumph of finally seeing the ending credits roll. It was more than just a game, it was an experience – a demanding, rewarding, and utterly unforgettable journey into the heart of ninja action and cinematic innovation on the NES.

Leave a comment