The Dawn of Console RPGs

Remember that ritual? Racing to the mailbox, maybe tearing open the plastic wrap right there on the curb, hoping the new Nintendo Power had arrived. That glossy cover, the specific smell of the paper and ink – it was like a portal opening. You’d devour the high scores, check out the latest game previews, maybe even read Howard & Nester. Sometimes, you’d hit a page that made you pause. Maybe it had some epic fantasy art, a knight facing a dragon, or this thing called an “R.P.G.”

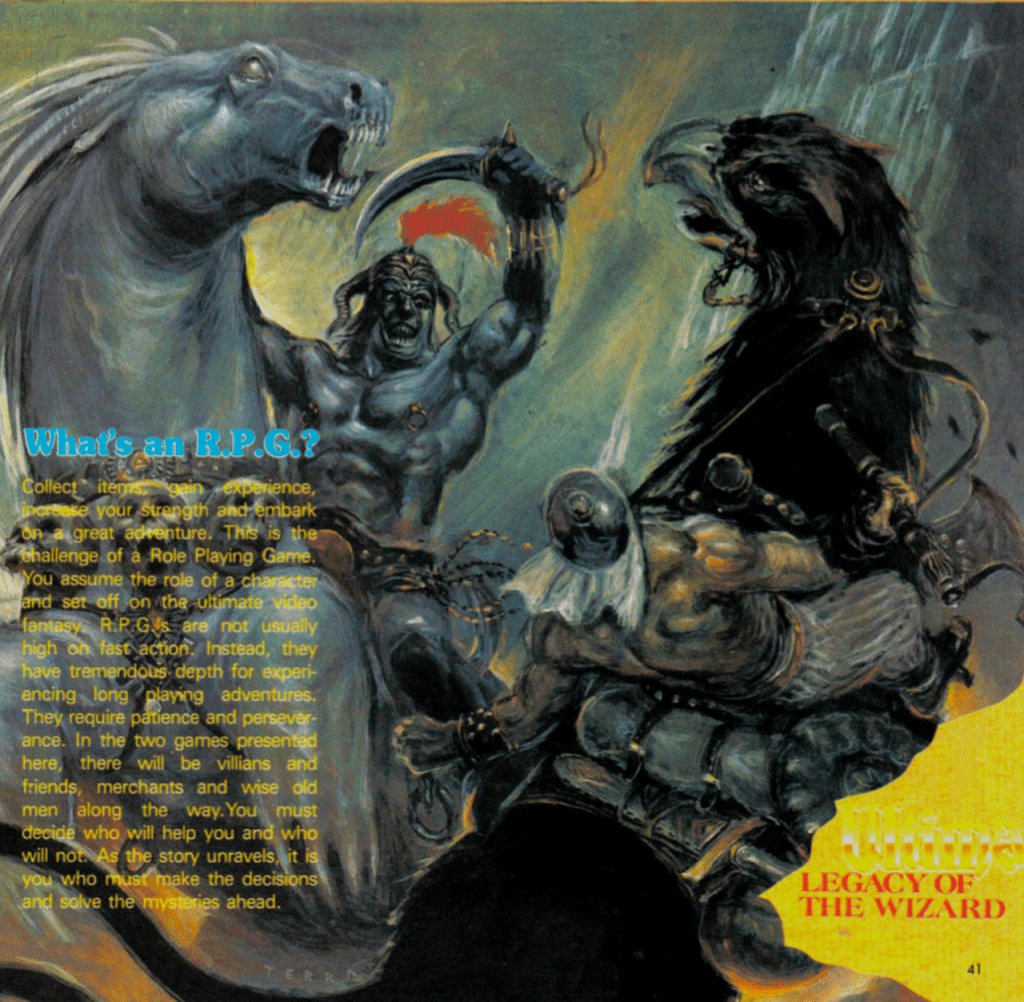

“What’s an R.P.G.?” the magazine would ask, like it knew you were wondering. The answer felt both simple and profound: “Collect items, gain experience, increase your strength and embark on a great adventure. They have tremendous depth and require patience and perseverance.” Patience? Perseverance? This sounded different from Contra.

The real head-scratcher, though, wasn’t just that these games felt different from other console fare. It was the nagging feeling, for some of us, that didn’t dad already have games like this? Maybe not on the NES in the living room, but perhaps on that mysterious beige box – the family computer – humming away in the family den? That machine ran games with sprawling maps, character sheets filled with baffling numbers, and stories that seemed to go on forever.

So why did these console RPGs, trickling in primarily from Japan, feel like such newcomers? Why the weird detour? It’s a fascinating story of two parallel gaming universes, defined by silicon, market forces, and wildly different ideas of fun back in the 8-bit glory days before 1990.

America’s Deep, Hidden World of Computer RPGs

Let’s be honest, for many American households in the 80s, the computer wasn’t primarily a gaming machine; it was for computer stuff, word processing, spreadsheets or maybe dabbling in Paint Shop printouts for the latest bake sale. But for a dedicated group, it was the gateway to worlds of unparalleled depth. Forget the bright colours and bleeps of the arcade; this was the realm of the CRPG – the Computer Role-Playing Game. Imagine basements lit only by the glow of a chunky CRT monitor, the rhythmic spin of a floppy drive accessing data, graph paper spread out like treasure maps.

This was the natural habitat for Richard Garriott’s legendary Ultima series where players weren’t just killing monsters; they were exploring Britannia, interacting with townsfolk using typed keywords, and grappling with a complex virtue system where choices had real consequences. It felt less like a game and more like a world.

Then there was Sir-Tech’s Wizardry. Forget hand-holding; the early entries were brutal first-person dungeon crawls through wireframe mazes. Permadeath was a constant fear, party composition was critical, and success felt earned after hours spent battling unseen horrors and praying your mapping skills were accurate.

These games were incredible, offering hundreds of hours of gameplay. But they were undeniably complex, often requiring players to read manuals thicker than phone books. This sophistication created a barrier. These deep RPGs existed in their own sphere, largely inaccessible and perhaps even unknown to the burgeoning audience flocking to the simpler, more immediate thrills offered by Nintendo and Sega on home consoles.

The technical gulf was vast – imagine trying to fit Ultima V’s world onto a tiny NES cartridge, or navigating Wizardry’s menus with just a D-pad and two buttons! Furthermore, the US console market, carefully rebuilt by Nintendo after the crash of ’83 with an emphasis on action, polish, and family fun, likely viewed these dense, slow-paced CRPGs as commercial duds for their audience. Why risk publishing a complex stat-fest when Super Mario Bros. was selling millions?

Japan’s obsession with RPGs

Fly across the Pacific to Japan, however, and the scene couldn’t have been more different. Here, consoles weren’t just part of the gaming landscape, they were the landscape. Nintendo’s Famicom reigned supreme, a cultural fixture in millions of homes.

But even before Dragon Quest cemented that royal status on the Famicom, the initial spark was ignited on Japanese computers. The crucial proof of concept came from an unlikely source: a Dutch developer living in Japan named Henk Rogers (the same man who would later secure the rights for Tetris). Rogers was captivated by American CRPGs like Wizardry but found them too complex and inaccessible for a Japanese audience. His solution was The Black Onyx, a streamlined, Japanese-language RPG for platforms like the NEC PC-88. It was an absolute blockbuster, becoming the best-selling computer game in Japan and proving beyond a doubt that the nation was starving for this new genre. This success was the green light, the blueprint that inspired Yuji Horii and others to take that core formula and adapt it for the Famicom’s massive audience.

And on the Famicom, RPGs weren’t a niche genre, they quickly became the undisputed kings, generating a level of national excitement rarely seen for any form of entertainment.

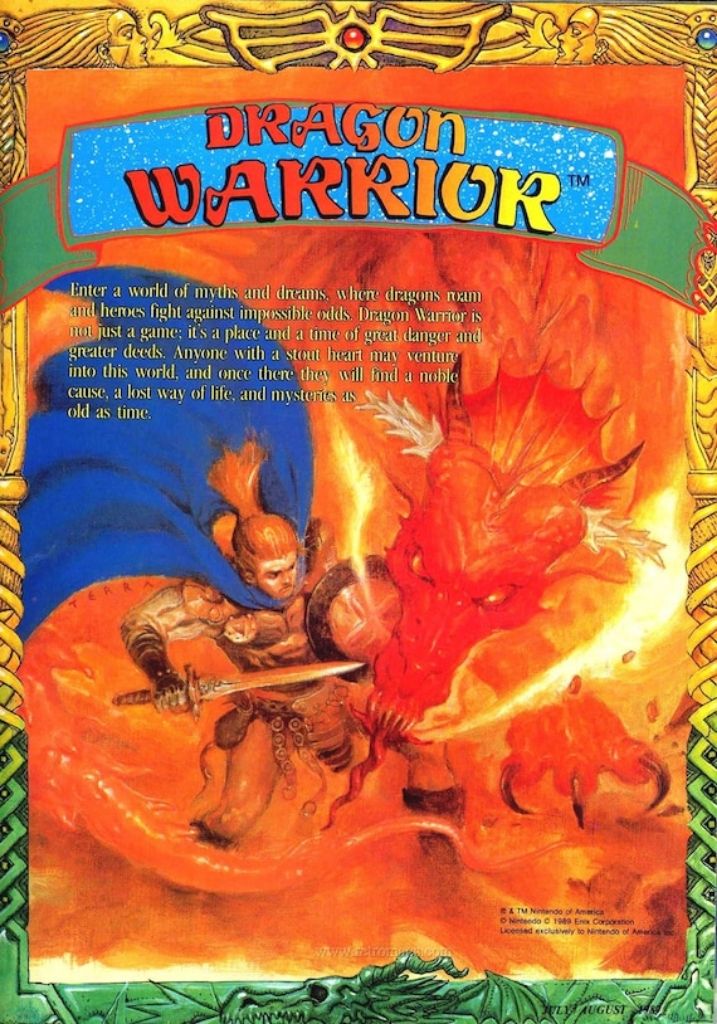

You didn’t need insider reports to know this, you could see it right in the pages of Nintendo Power’s “NES Journal”! Reporting on the February 1988 release of Dragon Quest III, the magazine declared it “the talk of Japan today!” Enix, the game’s creator, projected a mind-boggling five million copies sold. Think about that number in 1988 – it was astronomical! The article even noted a cultural shift: “Ninjas and Kung-Fu Masters are no longer heros to Japanese players since they are now being replaced by warriors and sorcerers who bravely confront dragons…” This wasn’t just a game, it was reshaping pop culture heroes in real-time. This unprecedented frenzy spawned the enduring legend of the “Dragon Quest Curfew” – the rumour that so many students were skipping school to play DQ that the government itself asked Enix to release future sequels only on weekends or holidays to maintain national productivity! True or not, the legend perfectly encapsulates the game’s societal impact.

Why such devotion? Dragon Quest, masterminded by Yuji Horii, hit a cultural sweet spot. It took inspiration from those complex Western CRPGs but brilliantly streamlined the mechanics for the Famicom controller, making the adventure accessible. Akira Toriyama’s instantly recognizable character and monster designs tapped directly into the nation’s love for manga and anime. The music was catchy and heroic, the stories epic yet easy to follow. It was a shared national experience, something friends discussed excitedly in schoolyards across the country.

Encountering these first localized JRPGs was certainly a unique experience for many of us. The sense of exploring a truly large world, the quiet satisfaction of watching your character get stronger, the thrill of discovering hidden secrets or finally beating a tough boss after careful preparation – it was a different kind of fun, deeper and arguably more rewarding in the long run than simply chasing a high score. These games, strange as they might have first appeared, were planting the seeds for a whole new generation of dedicated console RPG fans in North America.

Square’s Final Fantasy offered a slightly different, perhaps more dramatic flavour. Choosing your party classes from the start felt empowering, the side-view battles were more visually dynamic, and the storyline felt grander, more influenced by Western fantasy epics but retold with a distinctly Japanese narrative sensibility.

And, of course Sega wasn’t sleeping. On the Master System, Phantasy Star was a technical marvel and a creative triumph. Its blend of laser guns and dragons felt fresh, its determined female protagonist Alis was a welcome change, and its first-person 3D scrolling dungeons felt like stepping into the future, a clear nod to Wizardry.

The circuitous route makes sense in this context. Our NES and Master System just weren’t equipped to handle the data-heavy, keyboard-dependent behemoths from the US PC scene. But they could run the games coming out of Japan, which were already designed and optimized for very similar console hardware. It was infinitely easier, though still a significant undertaking, for companies like Nintendo, Sega, and eventually Square, to translate the text, navigate the cultural differences, and sometimes censor content for their Famicom or Master System hits to bring them to the NES or Sega Master System in America.

Crossing the Ocean: Explaining the Weird Detour

So, picture yourself as a North American kid in 1989. You love your NES. You hear about these “RPG” things. Maybe you see an ad for Dragon Warrior. It looks kind of slow. Lots of menus. You have to read? It feels worlds away from the instant action you’re used to. You had no idea that a whole genre of even more complex RPGs existed on computers, because that scene was largely invisible to the console market. And you had no idea that the game you were seeing, Dragon Warrior, was the simplified, console-friendly ambassador from a country utterly obsessed with its particular brand of RPG.

Encountering these first localized JRPGs was certainly a unique experience for many of us. The sense of exploring a truly large world, the quiet satisfaction of watching your character get stronger, the thrill of discovering hidden secrets or finally beating a tough boss after careful preparation – it was a different kind of fun, deeper and arguably more rewarding in the long run than simply chasing a high score. These games, strange as they might have first appeared, were planting the seeds for a whole new generation of dedicated console RPG fans in North America.

8-Bit RPG Memories: Worlds Collide

It was a time when graphics were simple enough that your imagination had to do heavy lifting, filling in the details suggested by those chunky pixels and beeping soundtracks. It was a time of discovery, realizing that the same grey box that let you shoot ducks or rescue princesses could also transport you to sprawling fantasy kingdoms demanding hours upon hours of exploration. The journey RPGs took to American living rooms was winding, shaped by technology gaps and different cultural appetites, but the arrival of those first few Japanese imports sparked a slow-burning fuse that would eventually ignite a massive love for the genre on consoles for years to come. It was the quiet beginning of something truly epic.

Leave a comment