What is Best in Life?

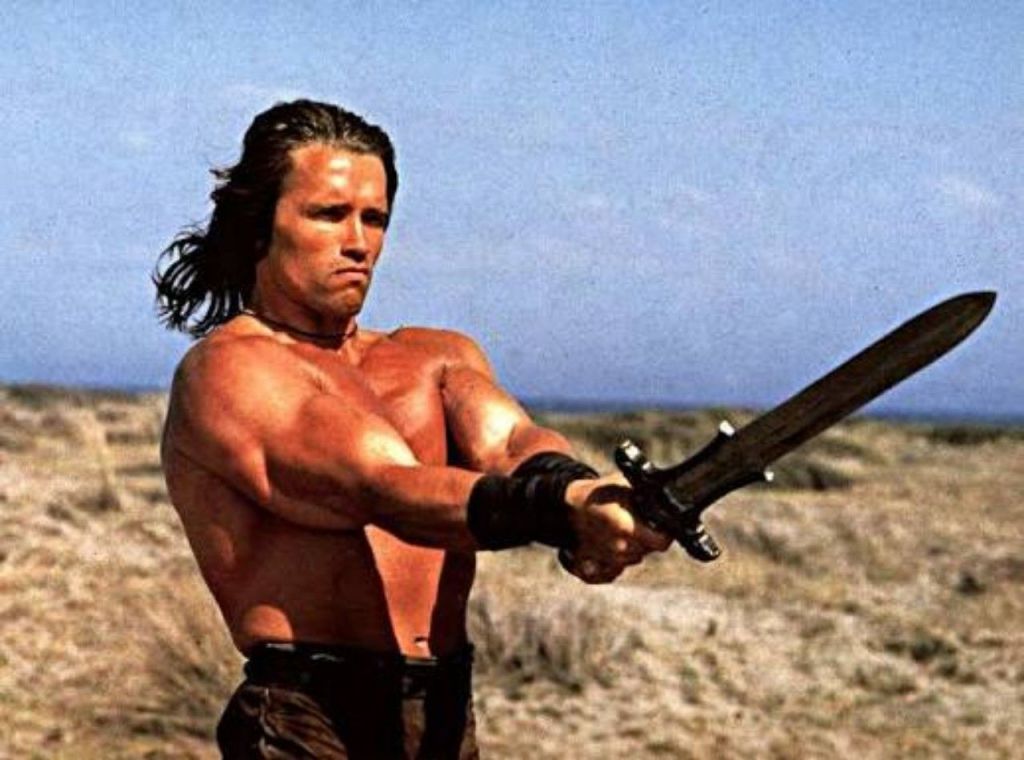

To crush your enemies, see them driven before you and to hear the lamentation of their women. That line was the heartbeat of the eighties. It was a decade absolutely obsessed with sword and sorcery movies headlined by glistening baby oiled bodybuilders. We grew up watching Arnold Schwarzenegger and the barbarian craze where heroism was defined by how big your sword was and how hard you could swing it. We desperately wanted to live out that fantasy. We wanted to be the savage warrior cleaving through hordes of monsters. The problem was that our video games were mostly cute little sprites backed by light hearted sound tracks. We needed something beefier, a game that let us feel the true weight of a battle-axe in our hands.

To get there we had to break free from the chains of king NES’ fiefdom. Nintendo had a total lock on the market by single handedly saving the video games industry after it crashed and burned in 1983. But by 1989 the old grey toaster was looking tired. The colors were muddy and if you had more than a few enemies on screen they would start flickering and the action would slow to a crawl. The arcade experience was light years ahead of what we had at home and we were all waiting for something to close that gap.

That is when a new challenger stepped into the ring to shake things up. NEC had unleashed the PC Engine in Japan and rebranded it as the TurboGrafx-16 for us in North America. This console was a total step up from the NES. It was an often misunderstood hybrid of a console that paired an 8-bit CPU with dual 16-bit graphics processors.

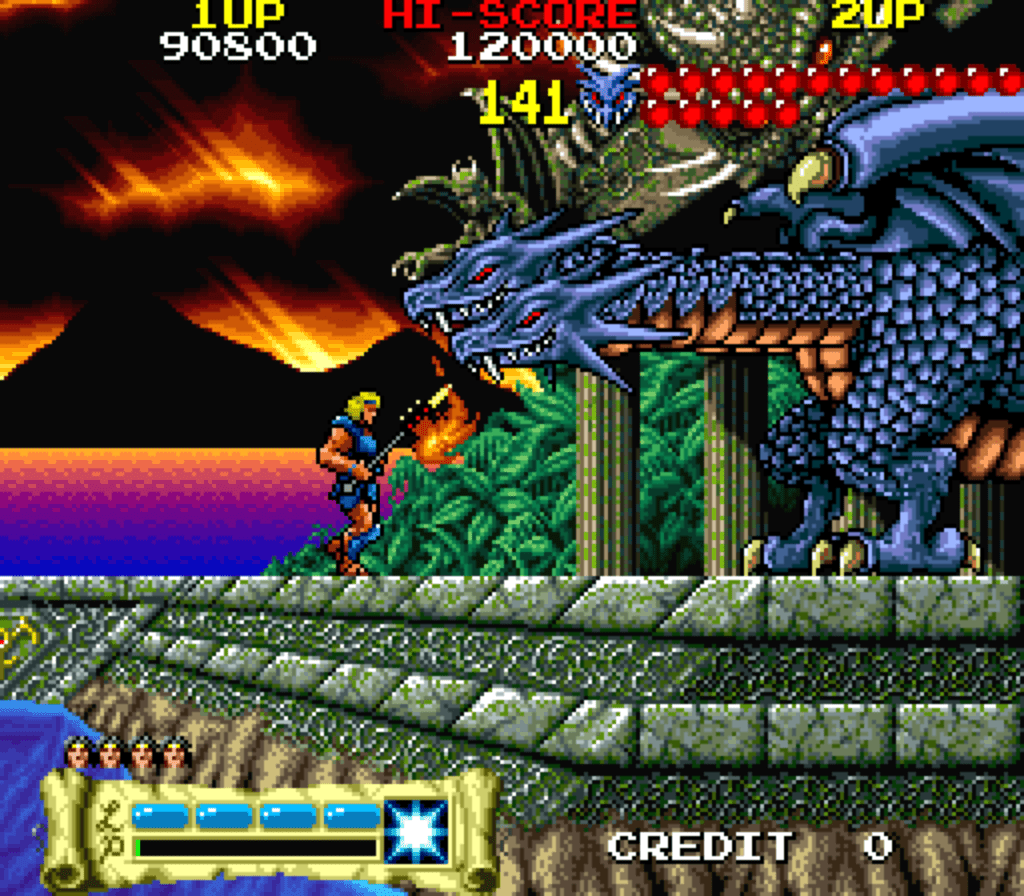

That weird architecture meant it could push massive colorful sprites that made the NES look like a pocket calculator. NEC was gunning for older gamers who were tired of cute platformers and wanted arcade perfect graphics. While there were plenty of games on the shelf, only one title truly let us live out our sword and sorcery fantasies and that game was The Legendary Axe.

A Tale of Two Pack In Games

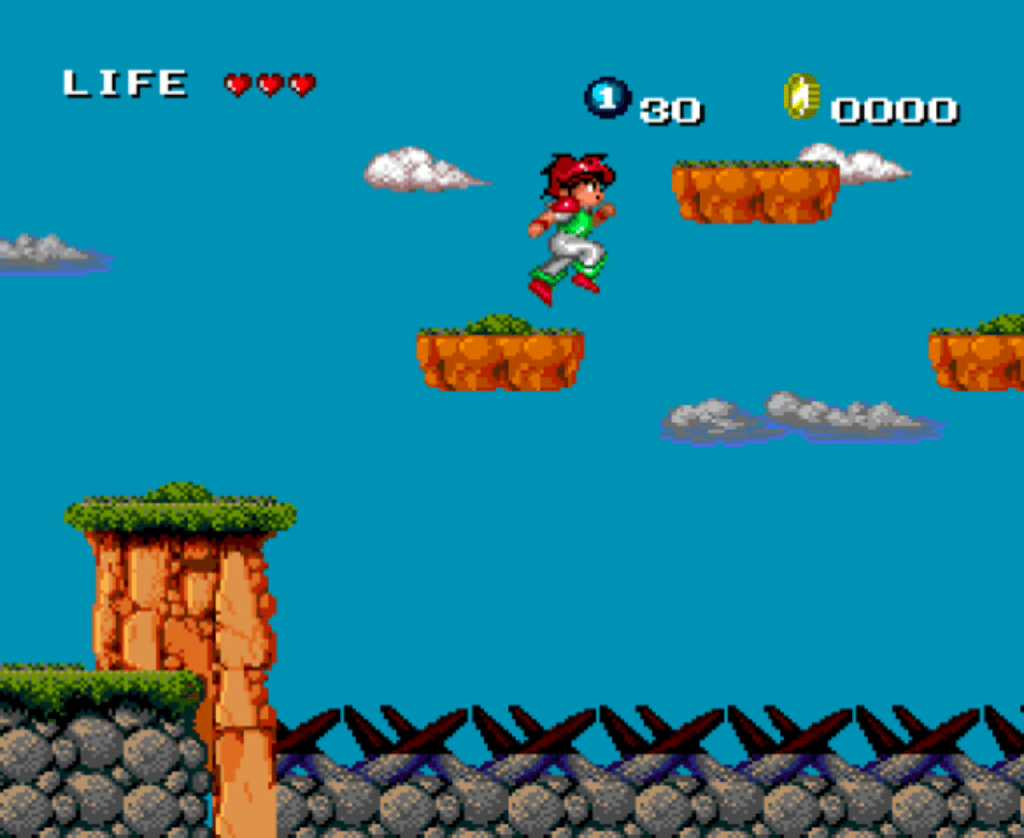

The success of failure of new consoles often hinge on a few key decisions and NEC made a controversial decision in 1989 regarding their launch bundle. When consumers purchased a TurboGrafx-16 it came with Keith Courage in Alpha Zones. This was a localized version of an anime based game called Mashin Hero Wataru. While it was colorful, it suffered from repetitive gameplay and a generic aesthetic that failed to communicate the generational leap to the Western market. This decision severely hampered the initial momentum of the console as it didn’t immediately grab the attention of the older demographic NEC was courting.

The Legendary Axe would have been the superior choice for the pack in title. The game was a visual powerhouse that immediately showcased the system strengths. It featured massive character sprites and detailed background textures along with a crunchy audio profile that sounded distinct from the NES. The exclusion of The Legendary Axe from the bundle was a huge mistake that punished early adopters by forcing them to make an additional purchase to truly see the power of their new console. While Keith Courage languished in mediocrity, The Legendary Axe became the de facto demonstration disc for the system and proved that the TurboGrafx-16 was a legitimate contender in the 16-bit wars.

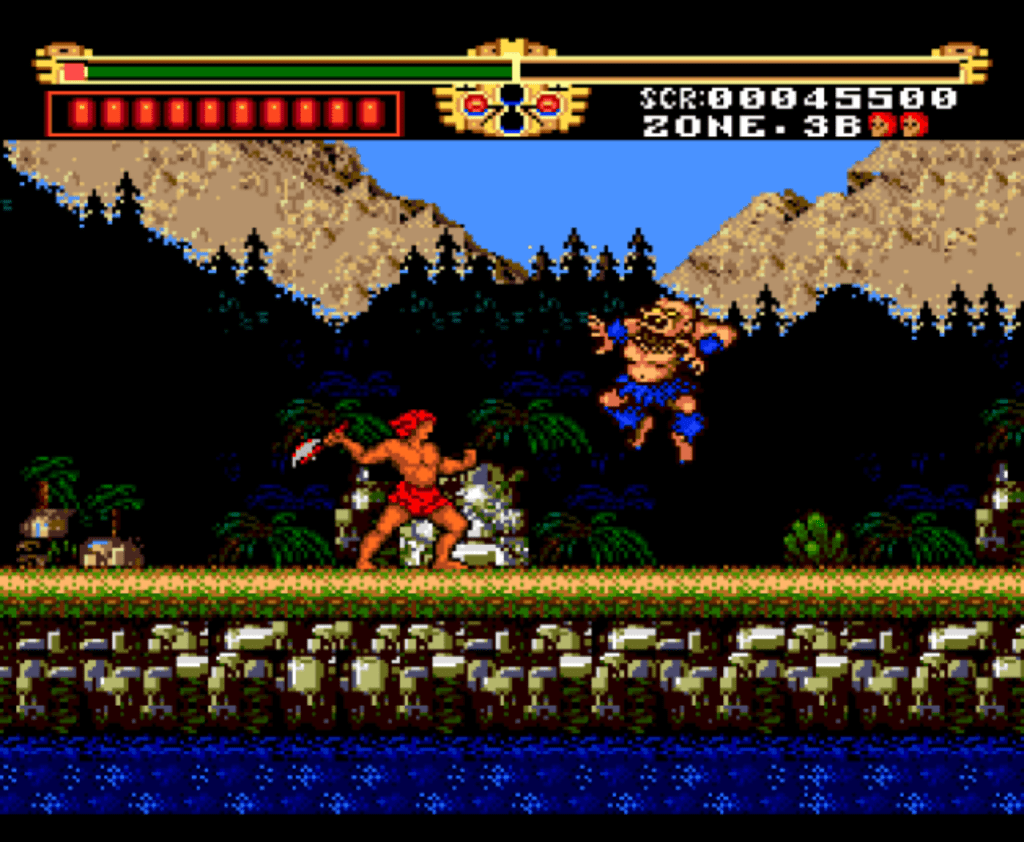

Instead of leading the TurboGrafx-16 launch with an anime hero no one had heard of, NEC could have slammed into the North America market at the height of Barbarian mania with a protagonist that looked like he was ripped straight out of the Conan films. His name was Gogan, wearing a simple fur loincloth and wielding a massive weapon that wrought destruction upon his enemies. The character design leveraged the hardware’s ability to render large multi-colored sprites which gave Gogan a muscular definition and weight that 8-bit characters lacked. This physicality was central to the experience as the character performance is defined not by acrobatic finesse but by raw power and endurance.

Gogan is a force of nature who destroys his enemies through sheer strength and his movement in the game is deliberate. He does not sprint with kinetic energy but rather he strides. His jumps are heavy and governed by a momentum based physics engine that commits the player to their trajectory once airborne. This heavy physics model simulates the sensation of controlling a densely muscled warrior rather than a springy avatar.

Rhythm is a Slasher

The central question of the genre regarding whether the flesh or the steel is stronger is gamified through the central mechanic known as the charge meter, separating the game from all the mindless button mashers of the time. The axe, Sting, is not merely a tool but a legendary artifact with a presence of its own.

Located at the top of the HUD the bar fills automatically when the player is idle or moving without attacking. A fully charged meter allows Gogan to unleash a strike that deals massive damage which often kills standard enemies in a single hit. However swinging the axe depletes the meter instantly. If the player simply mashes the attack button the meter never has a chance to recharge resulting in a flurry of weak low damage attacks.

This system imposes a rhythm upon the player. It transforms combat from a test of reflex speed to a test of pacing and timing. You have to evaluate each enemy and ask if you can kill it with one charged hit or if you need to whittle it down. You must decide if you have the time to let your axe charge before the enemy reaches you. This creates constant tension in every encounter and elevates the combat to a tactical engagement.

A Journey to the Evil Place

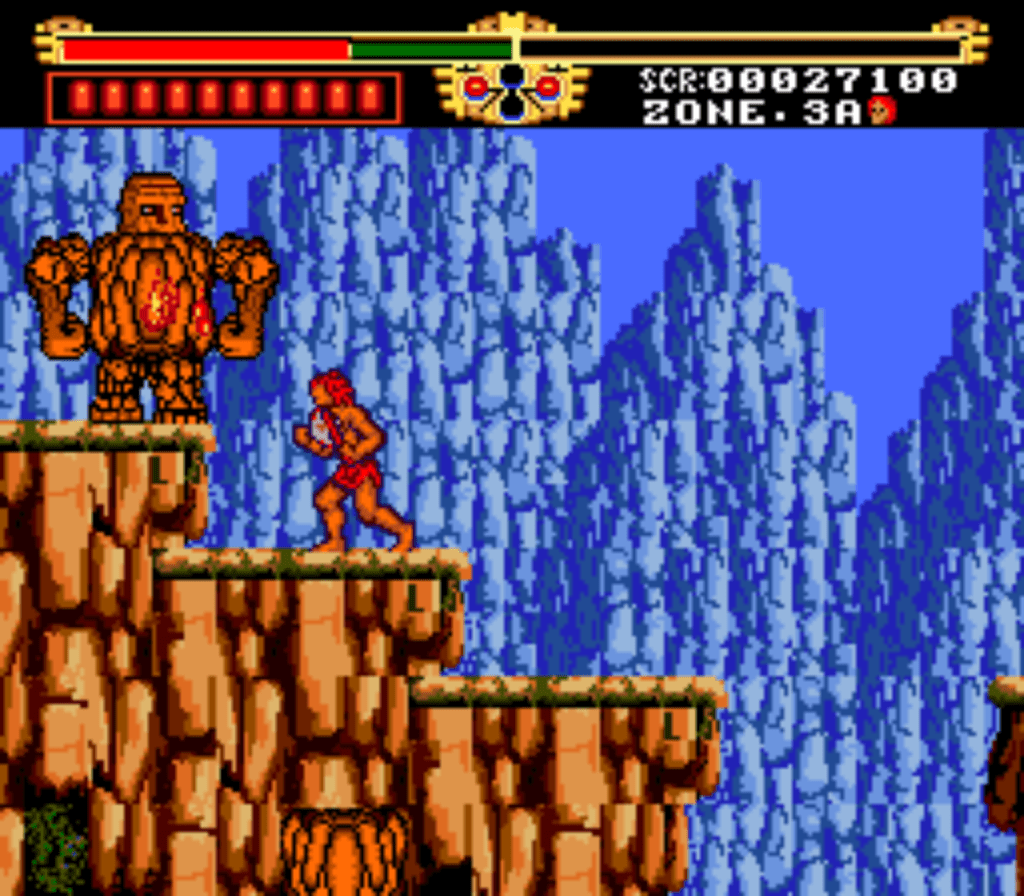

The game progression is structured to teach and then test the mastery of its mechanics through a journey of escalating complexity. The adventure begins in a lush forest environment, establishing the system’s visual fidelity and introducing the player to weak enemies that allow for easy experimentation with the central charge meter mechanic. This initial stage is an upbeat introduction to the core gameplay.

The path quickly shifts, transitioning to subterranean and mountainous zones. These stages change the color palette to darker tones and dramatically increase the environmental hazards. Tight corridors and the heavy physics model make platforming treacherous, emphasizing close-quarters combat and introducing projectile threats that demand precise timing and movement.

Next, the player delves into ancient, man-made architecture like dungeons and fortresses. Here, the challenge focuses on movement precision, with the landscape dominated by spikes and crushing blocks, and the player is harassed by small, erratic enemies. The journey culminates in the stronghold of the Jagu cult, a menacing environment that introduces large, highly durable enemies. These encounters demand advanced combat strategy, forcing the player to master the rhythmic dance of striking, retreating, and charging the axe.

Finally, the player must navigate a sprawling, non-linear labyrinth that subverts the expectations of previous areas. This final test requires exploration and backtracking to find keys and progress. The journey concludes with the multi-stage final boss, a grotesque monstrosity that requires the player to demonstrate every ounce of learned mastery over the charge meter mechanic.

The Philosophy of Heft

The design success of The Legendary Axe was the culmination of a clear philosophy from its developer, Aicom Corporation, who sought to distinguish themselves from other developers by focusing on heft rather than speed. This ethos was first attempted on the NES with Amagon, which served as a rough proof of concept. That title featured a marine transforming into a hulking giant, signaling Aicom’s desire for characters that physically dominated the screen. However, the 8-bit hardware struggled to fully support this ambition, resulting in a game where the concepts of weight and power were hampered by technical limitations and slippery controls.

It was only on the TurboGrafx-16, freed from the restrictions of the NES, that the studio could fully realize its vision. Aicom replaced the clumsy transformation mechanic with the more elegant charge meter, forcing players into a deliberate, rhythmic combat style rather than simple button mashing. The superior hardware allowed for the large, detailed sprites they had always aimed for, with fluid animation and responsive controls that successfully married their heavy visual style with tight, rewarding gameplay. This evolutionary step proved that the feeling of weight could be a central feature of a compelling action game.

This evolution culminated shortly after with the arcade release of Astyanax, the unbound expression of Aicom’s design ethos. With the superior processing power of an arcade cabinet, the developers amplified the blueprint of The Legendary Axe to epic proportions, featuring massive characters that took up huge portions of the screen. If Amagon was the experimental struggle and The Legendary Axe was the refined solution, Astyanax was the victory lap, showcasing a developer that had finally mastered the technology required to make players feel the true weight of digital power.

The Barbarian in Our Living Room

The Legendary Axe stands as a monument to the 16 bit transition. It captured a fleeting moment where the technological leap of the PC Engine allowed developers to realize the aesthetic ambitions of the eighties fantasy boom. It was Gogan who allowed gamers to wield the heavy steel and feel the weight of the axe in their living rooms. Its gameplay loop governed by the discipline of the charge meter remains a masterclass in game design proving that limitations can birth strategic depth.

While the franchise was short lived, the influence remains. Every time a modern game utilizes a charged attack mechanic or employs environmental storytelling to build a dark fantasy world it walks the path cleared by Gogan. The Legendary Axe remains sharp and stands as a testament to the era when gaming finally grew the muscles to match our imaginations.

Leave a comment