Corporate Conquest

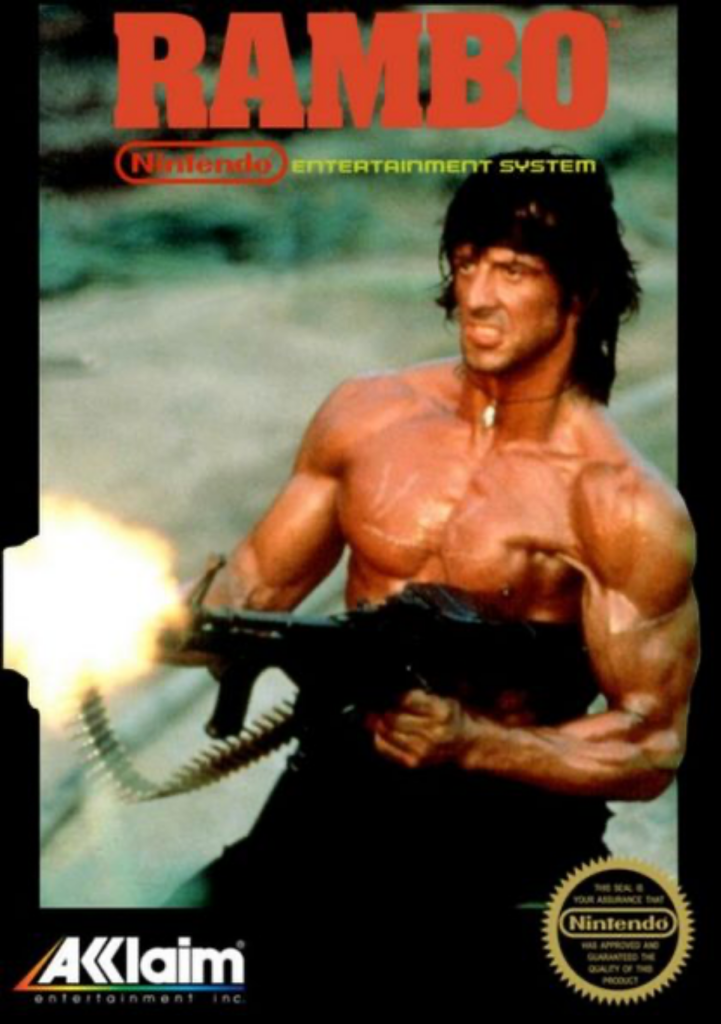

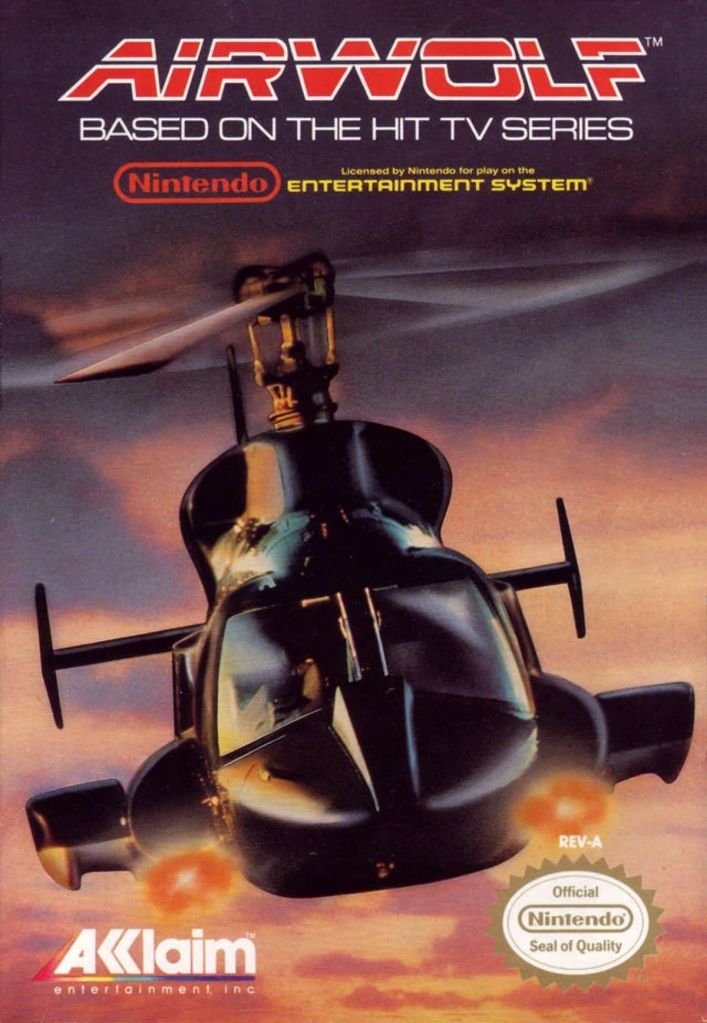

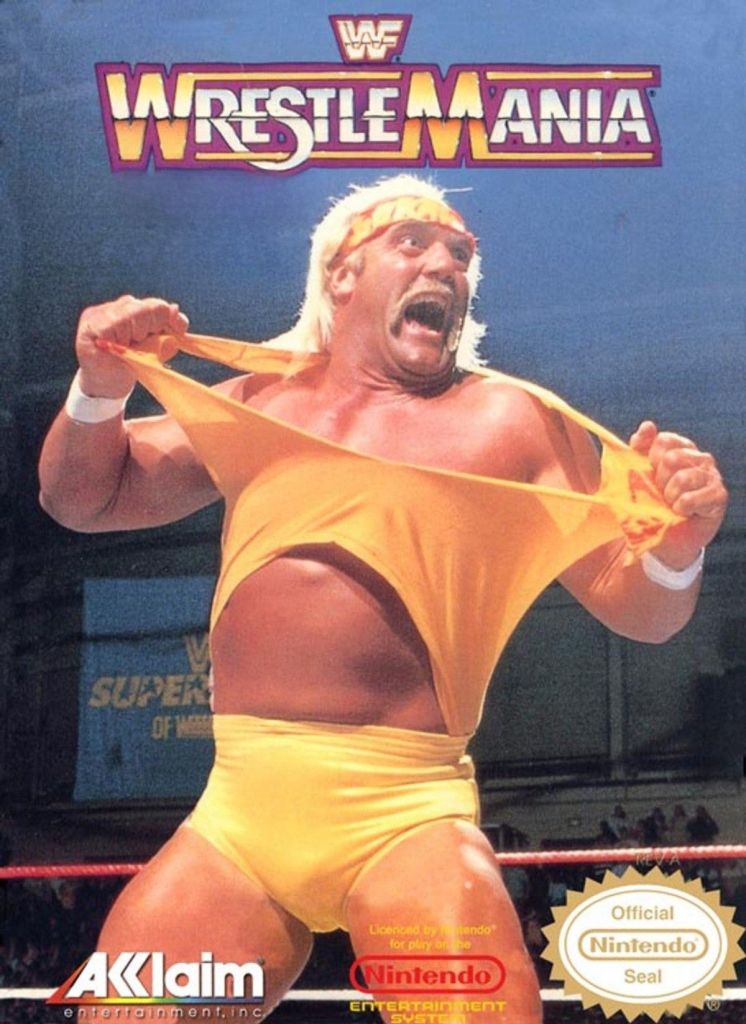

If you grew up blowing into cartridges and begging your parents for a rental on a Friday night you know the feeling well. You walked into the video store and scanned the rows of games. You were looking for that spark of recognition. Maybe it was a movie you loved or a cartoon you watched on Saturday mornings. More often than not you ended up holding a box with a distinct logo on it. It was a stylized arrow pointing the way to excitement or perhaps disappointment. That logo belonged to Acclaim Entertainment.

For a massive chunk of the 8-bit and 16-bit eras Acclaim was everywhere. They were the heavy hitters of the playground and the kings of the rental aisle. But while we were busy memorizing cheat codes and trying to beat Wizards and Warriors there was a fascinating corporate machine humming along in the background. The story of Acclaim is not really a story about game design at all. It is a story about lawyers and suits and a business model borrowed entirely from the rock and roll industry. It is a tale of how one man looked at a Nintendo cartridge and saw a vinyl record.

From the Courtroom to the Console

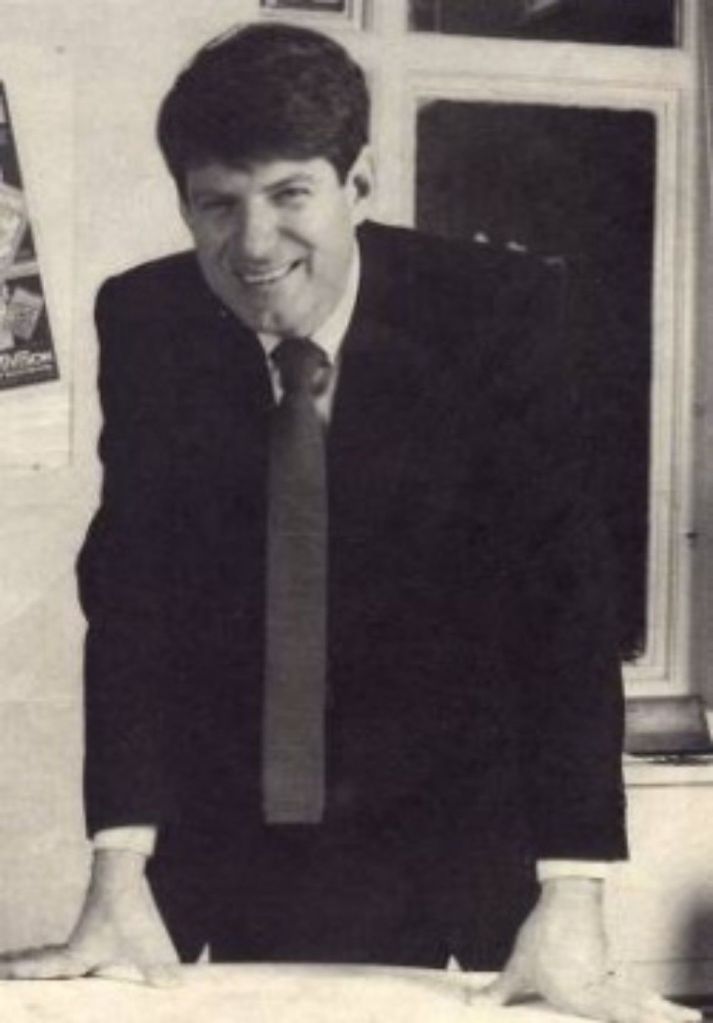

To understand why your copy of Turok or NBA Jam existed you have to look at the man sitting in the big chair. His name was Gregory Fischbach and he was about as far from a game designer as you could get. He was not staying up late hacking code or dreaming of plumbing adventures. He was a suit, working his way up the corporate ladder.

Fischbach started his career working for the Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Department of Justice. The guy who eventually brought us Mortal Kombat on home consoles started out navigating federal frameworks and litigating aggressively in courtrooms. This legal background gave him a weapon that most game devs lacked, the ability to find legal loop holes and profit from them.

But the real magic happened when he left the government life and dived headfirst into the music industry of the 1970s. This is where the DNA of Acclaim was truly formed. He represented legends like Crosby Stills and Nash and Thin Lizzy. He saw how the music business worked from the inside. He learned that the product was not the vinyl disc itself but the license and the intellectual property. He saw that record labels did not usually write the songs. They found the talent and packaged it and sold it. He carried this philosophy with him when he became President of RCA Records International in the mid-80s. He learned about global licensing and the power of a star system.

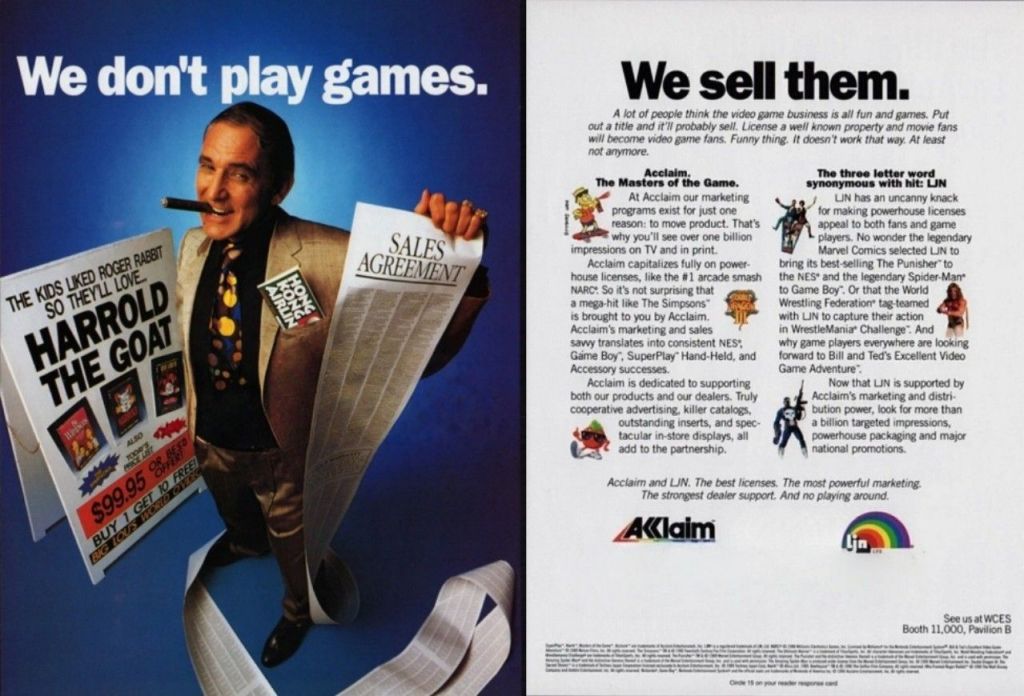

When he found himself out of a job after RCA was sold he did not go back to law. He met up with some old colleagues in an Oyster Bay storefront in 1987 and sketched out a business plan on a napkin. They decided to start a video game company. But they weren’t going to make games. They were going to sell them.

Guns for Hire

Fischbach treated the video game industry exactly like the music industry. In his mind Acclaim was the record label. The developers were just session musicians. You don’t usually know the name of the drummer on a pop hit and Fischbach didn’t think you needed to know who coded your game either. Acclaim was different from their competitors because they didn’t have a dependent development group that worked solely for them. He saw this as a privilege. It allowed him to search the world for good products and good developers rather than being stuck with an in-house team.

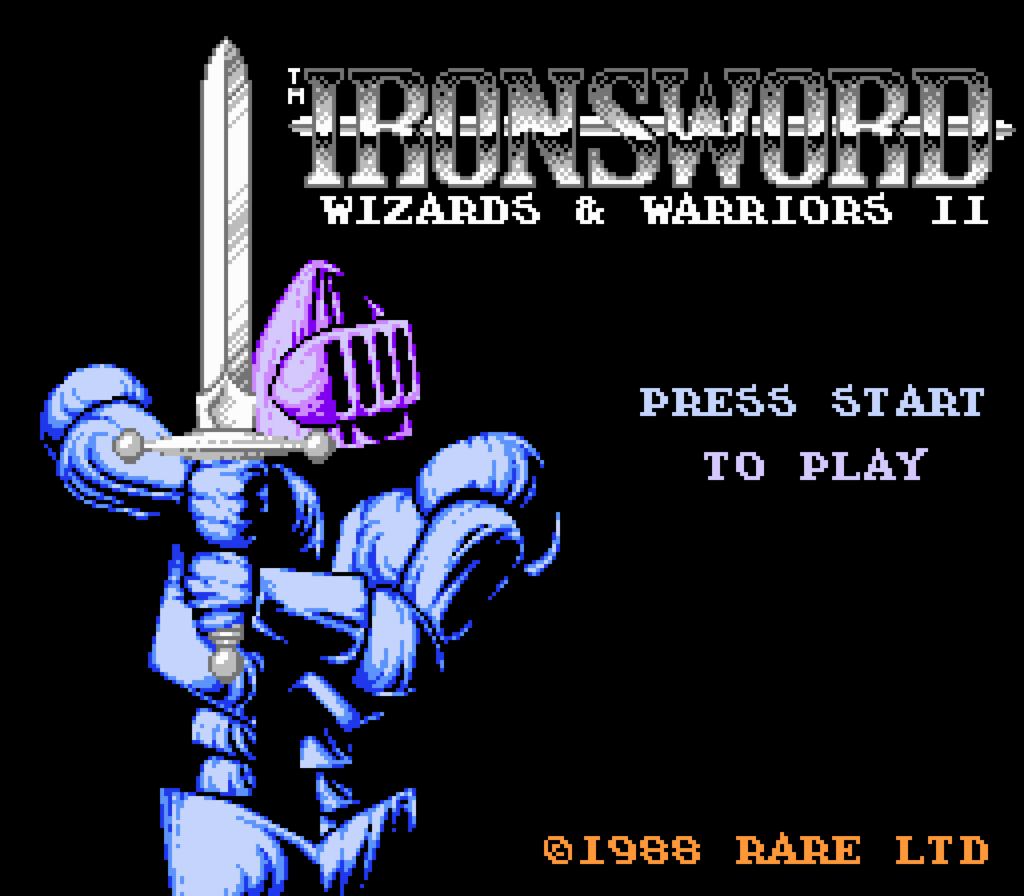

This is where studios like Rare came in. We all know Rare now as the legends behind GoldenEye and Banjo-Kazooie. But back in the late 80s they were the ultimate session musicians for the Acclaim label. Rare was a technical powerhouse that could pump out games faster than Nintendo allowed them to release. Acclaim became their outlet. Acclaim acted as the label holding the purse strings and distribution rights while Rare provided the raw product. It was a symbiotic relationship that flooded our living rooms with content.

The Garbage at the End of the Rainbow

If you were a kid in the 90s you remember the rainbow. You would see that colorful rainbow logo on a cartridge label and you would feel a mix of curiosity and dread. That was the logo of LJN. Acclaim bought LJN in 1990 and it was one of the slickest moves in gaming history. Nintendo had a strict rule to prevent a market crash. They limited third-party publishers to releasing only five titles a year. This was supposed to ensure quality. But for a guy like Fischbach who wanted volume and market saturation this was a disaster.

So he bought a loophole. By acquiring LJN he effectively bought a second publishing slot. This allowed Acclaim to double their output. They created a two-tier system that defined many of our childhoods. The main Acclaim label was reserved for the A-side hits and arcade ports like Double Dragon II and eventually NBA Jam.

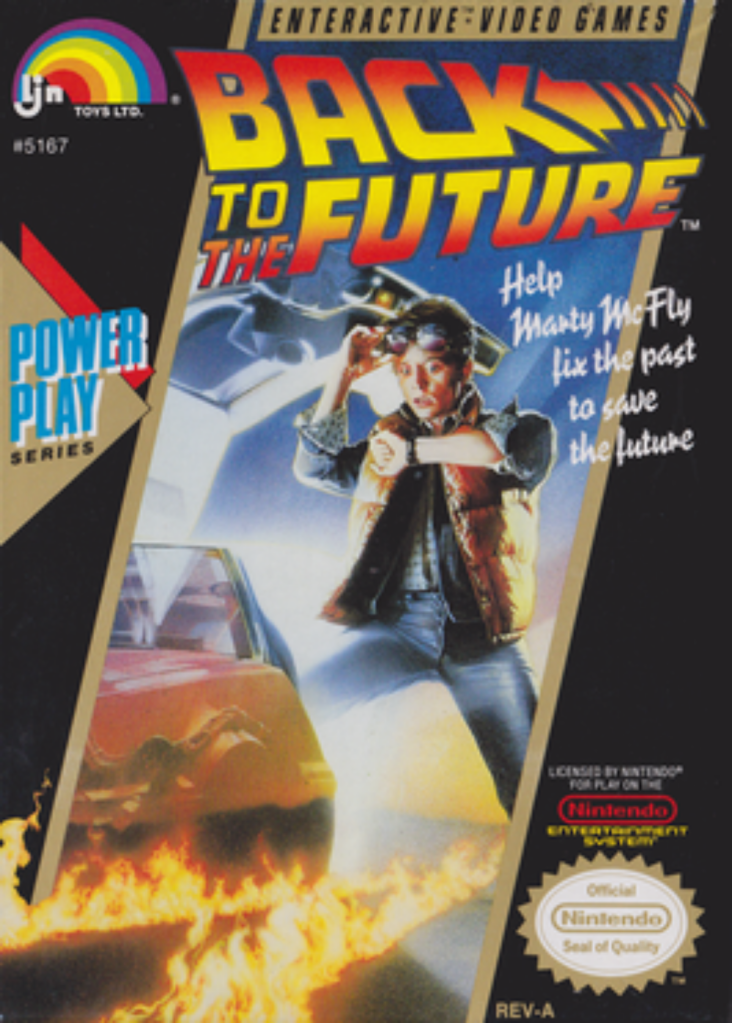

Then there was LJN. This became the burner label for B-tier licensed properties and movie tie-ins. It was the home of games based on Back to the Future, Terminator 2 and Who Framed Roger Rabbit. These games were often rushed and critically panned but they sold millions because they had famous names on the box. Acclaim crowded out the competitors by simply taking up more physical space on the store shelf. It didn’t matter if the game was bad if it was the only thing you saw.

The Man, The Myth, The Legend: Fabio!

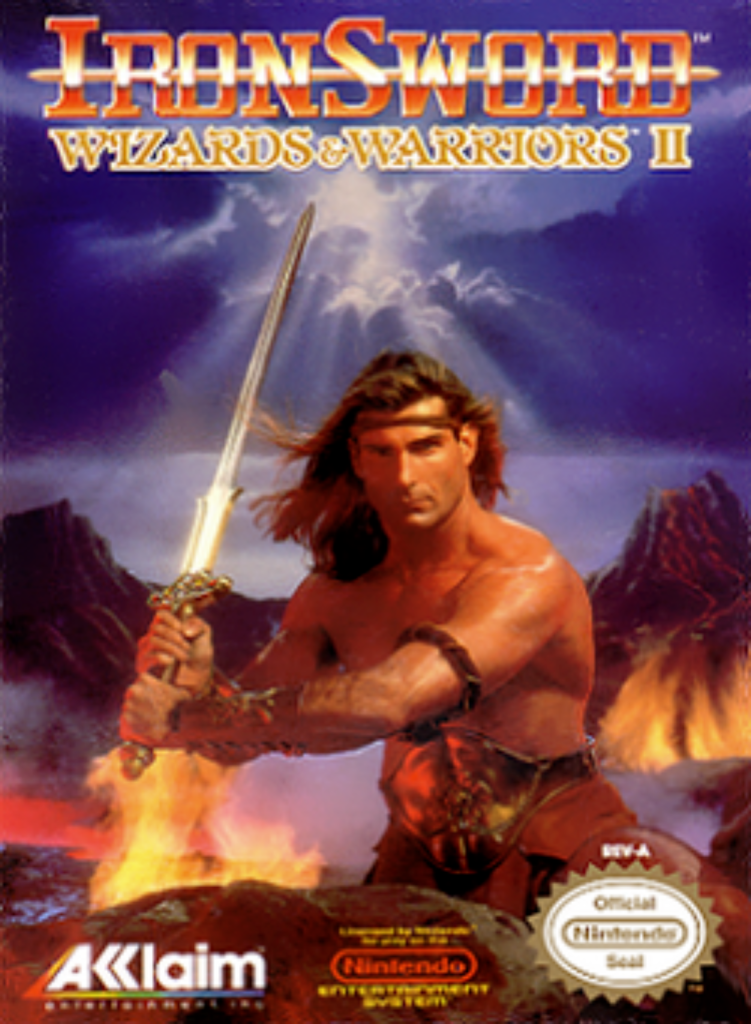

For Christmas 1989 Iron Sword was to be the crown jewel for Acclaim’s holiday offerings. The sequel to the hit game Wizards and Warriors, it was developed by a studio called Zippo Games which was another group of hired guns working under Rare. The game itself was actually quite good and featured some impressive technical tricks for the NES. But nobody talks about the code when they talk about Iron Sword. They talk about the cover.

Acclaim decided that the best way to sell this fantasy game was to hire the Italian model Fabio Lanzoni to portray the protagonist Kuros on the box art. At the time Fabio was the king of romance novel covers. He was a shirtless hunk with flowing hair and muscles that looked like they were carved out of marble. But Fabio had absolutely nothing to do with the game. He was not a digital sprite inside the cartridge. If you put the game in your NES you controlled a knight in full armor who looked nothing like the shirtless adonis on the box. But it didn’t matter. The image provided instant and visceral shelf appeal.

It was a tactic ripped straight from heavy metal album art. It grabbed your eye in a crowded store. Acclaim even ran a commercial that featured a Conan the Barbarian lookalike crashing into a kid’s bedroom. They were selling an aesthetic and a feeling. They were selling cologne and paperbacks to gamers. And it worked. IronSword sold over half a million copies in North America. It proved that you could decouple the marketing image from the actual software content and we would still eat it up.

The Wizards Behind the Curtain

While Fabio was flexing on the cover the real heroes were the developers at Zippo Games. These were the session musicians in the truest sense. The Pickford brothers who founded Zippo were talented artisans hired to execute a job for a flat fee. They worked in a grueling environment but somehow figured out how to create massive screen-filling bosses by combining multiple sprites and using the background layer for non-moving parts, something that had only been seen in a few titles before Iron Sword.

Because of their hard work Acclaim was able to market the game as a graphical powerhouse. But just like a session guitarist does not own the master recording Zippo did not own Iron Sword. They were paid to do a job and Acclaim reaped the rewards. Acclaim even rejected the logo Ste Pickford designed and replaced it with their own blocky corporate font. It was a reminder that while the creatives controlled the code the executives controlled the package. And in the Acclaim model the package was the product.

End of the Hype Train

As the industry moved into the 32-bit and 64-bit eras the old tricks started to fail. Gamers got smarter. Magazines got more critical. The session musicians started demanding more credit and autonomy. The shovelware model began to collapse.

Acclaim tried to adapt with even crazier marketing stunts. They offered money to parents who would name their baby Turok. They once considered paying for funerals if they could put an ad for Shadowman 2 on the tombstone. It was desperate and tasteless and a sign that the magic was gone. The cost of maintaining those expensive sports and movie licenses eventually became too much to bear. In 2004 the music stopped. Acclaim filed for bankruptcy and the label was shuttered.

Looking back at Acclaim is a tale of two publishers because on one hand they were responsible for a lot of frustration. We all rented a game because of a cool cover only to find a broken mess inside. We all learned the hard way that a movie license did not guarantee a good time. But on the other hand they defined the era. They gave us NBA Jam and Mortal Kombat II at home. They gave us the over-the-top marketing and the feeling that video games were a massive event.

Greg Fischbach and his team proved that a lawyer could orchestrate an industry. They showed that the business of games was just as creative and cutthroat as the design of games. They treated cartridges like vinyl records and developers like session musicians. And for a glorious decade or so they were the masters of the game. So the next time you spot a Fabio romance novel at a thrift store tip your hat to Acclaim. They might not have always made the best games but they knew how to build hype for a license.

Mag Coverage

Greg Fischbach: GamePro #3, Sep/Oct 1989

Leave a comment