The World in Your Pocket

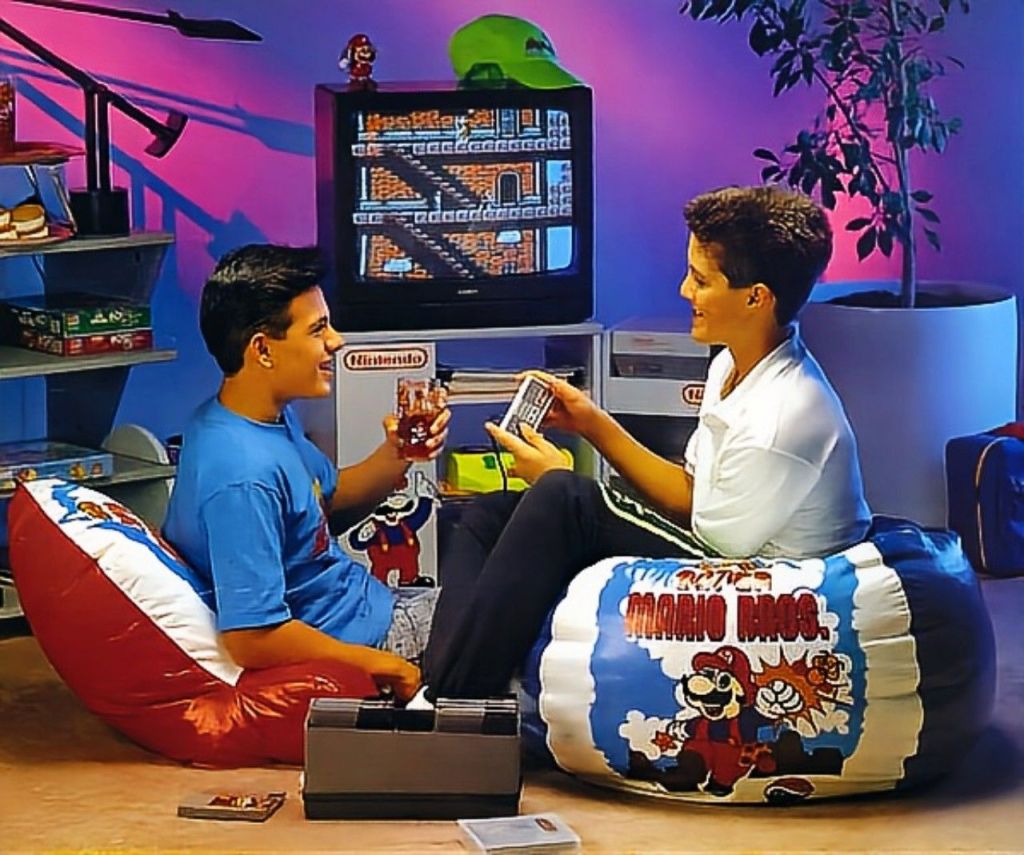

In 1989, entertainment was an appointment. You had to be on the couch at 8:00 PM to watch The Wonder Years or make sure the TV was free to play The Legend of Zelda. You couldn’t just watch it later or play in your room while your parents hogged the TV. Your world was anchored to the den. That glowing CRT was the center of your entertainment universe and you had to go to it. The NES, its gray plastic a familiar sight, was a permanent fixture of this one room. Our entire relationship with media was static. We were tethered and didn’t know that life could be different.

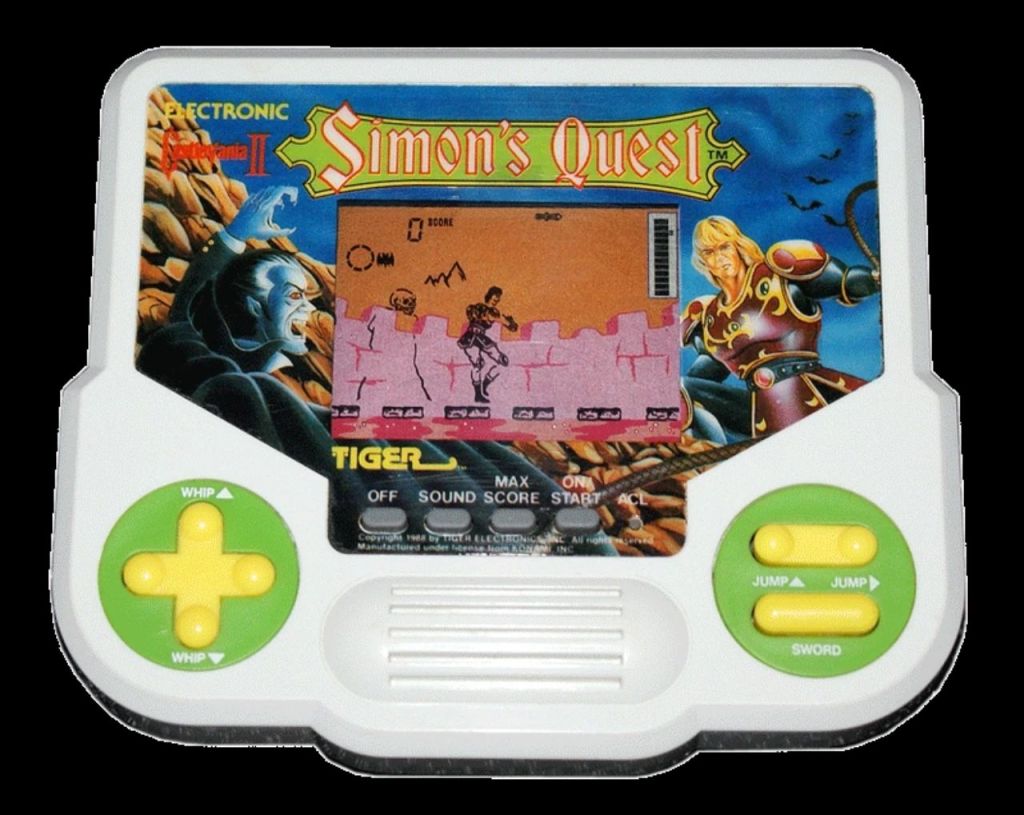

We had heard whispers all year that Nintendo was bringing gaming to our pockets. But we were skeptical, the idea of portable gaming up until now was a joke. It meant those flimsy, LCD-screened Tiger handhelds you got at RadioShack, chirping out pathetic beeps for Double Dragon or Castlevania. It meant a Nintendo Game & Watch, a fun five-minute diversion but not anywhere near as deep as the worlds you were getting lost in on your NES.

And then, in the fall of 1989, freedom arrived and gaming would never be trapped in our living rooms again. In the pages of Nintendo Power magazine we got a full feature on Nintendo’s new compact video game system called the Game Boy. It looked like a brick and its screen showed off some weird block game in four glorious shades of grey. But the words that came next made our hearts pound, “All the Power of the NES, Pocket-Size”. We stared at the page of cartridges and our minds imagined the impossible. Super Mario in our pocket, played wherever and whenever we wanted.

Lateral Thinking with Withered Technology

This entire design of the Game Boy was the masterpiece of Gunpei Yokoi and developed out of his philosophy of Lateral Thinking with Withered Technology. Withered didn’t mean bad, it meant mature. Yokoi’s genius was in taking components that were no longer cutting-edge but were, as a result, deeply understood, totally reliable, and, most importantly, dirt-cheap. He saw the surplus of Z80-based processors and monochrome LCD screens from the hyper-competitive calculator industry and had asked what if we used this cheap, proven tech to build a platform instead of just another toy?

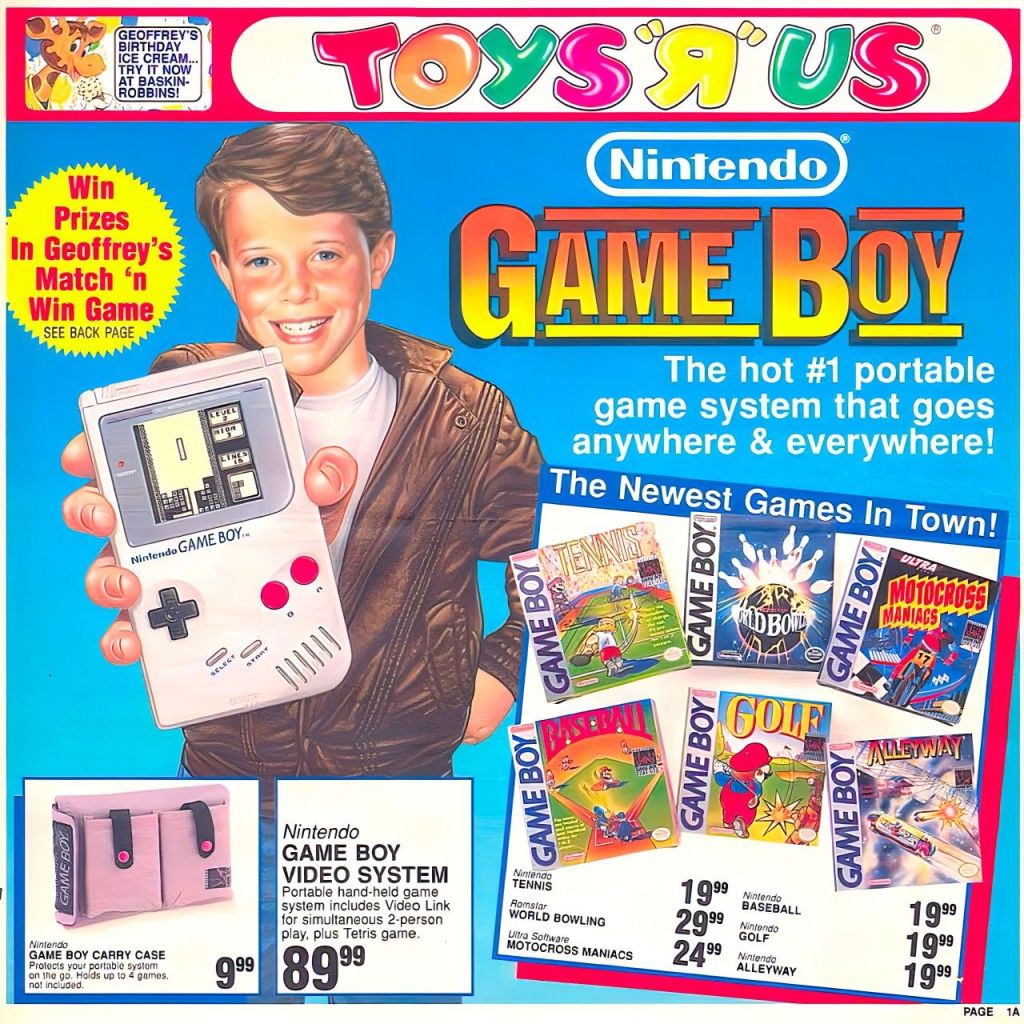

This philosophy was what gave the Game Boy its three unassailable features. First, the price. At $89.99, it was an ask, but it wasn’t an impossible one. It was a big birthday gift, not an unobtainable luxury. Second, durability, the system was indestructible and could survive a 10-year-old’s backpack or a fall from a bike. They were built to last. And the final, most important feature was battery life. The Game Boy ran for ten to twenty hours on just four AA batteries. The Game Boy’s marathon battery life meant it was a reliable companion. It was the first portable device you could trust on a long car ride. It was a revolution built on pragmatism.

Super Mario Hype

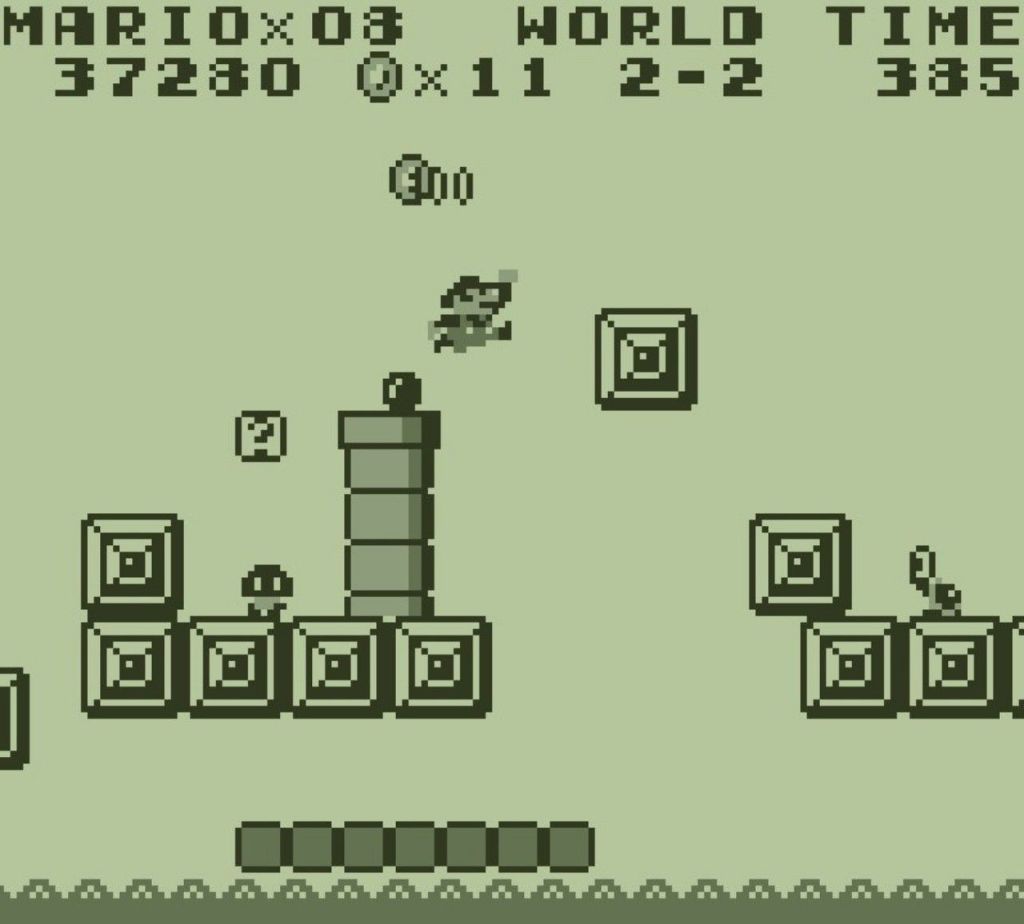

And while we were busy being excited for a pocket NES, little did we know it was a total and complete lie. The Game Boy was not a mini-NES, it couldn’t be. It was, in pure numbers, a far weaker machine. But we bought into the hype because of one game, Super Mario Land. This wasn’t a cheap, scaled-down, Tiger handheld simulation of Mario. This was a brand-new, full-featured, globe-trotting Super Mario adventure.

Developed by Gunpei Yokoi’s team, not Miyamoto’s, it had bizarre new enemies like the Sphinx-like Gira and exploding UFOs. It had shmup levels where Mario flew a plane or submarine. But it was still Mario, with its scrolling screens and exciting power-ups. The moment we stomped our first Goomba on that little screen, the marketing claim became a reality.

This oddball adventure was the proof. It was shorter than its NES counterparts, and the physics felt a little slippery. It took place in the strange new world of Sarasaland, where Mario fought aliens to save Princess Daisy, not Peach. Koopa shells didn’t just slide, they exploded into bombs. But the core magic was there. It proved the Mario formula was so airtight that it could survive being shrunk, simplified, and made a little weird and still be the pack-in game most NES owners would buy the system for.

The Soviet Secret Weapon

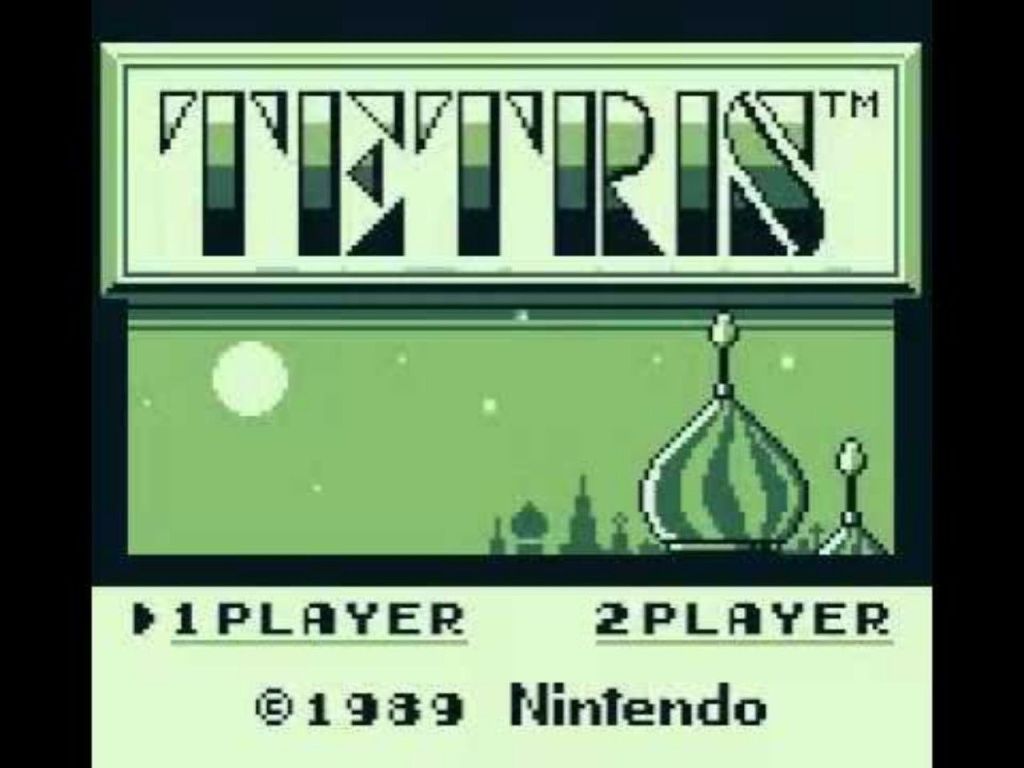

But while Mario would have been the perfect pack-in, Nintendo was about to receive a heaping dose of luck from heaven. Through the sheer determination and salesmanship of one man, Nintendo was handed the one single, undeniable, system-selling killer app. They found it not in the labs of Kyoto, but in the computing centers of the Soviet Union. Its name was Tetris.

The game, created by Alexey Pajitnov in 1984, was technically the property of the Soviet state, managed by an opaque entity called ELORG. By 1988, the rights were a tangled mess of sub-licensing deals, with multiple companies believing they had the console rights based on legally dubious contracts.

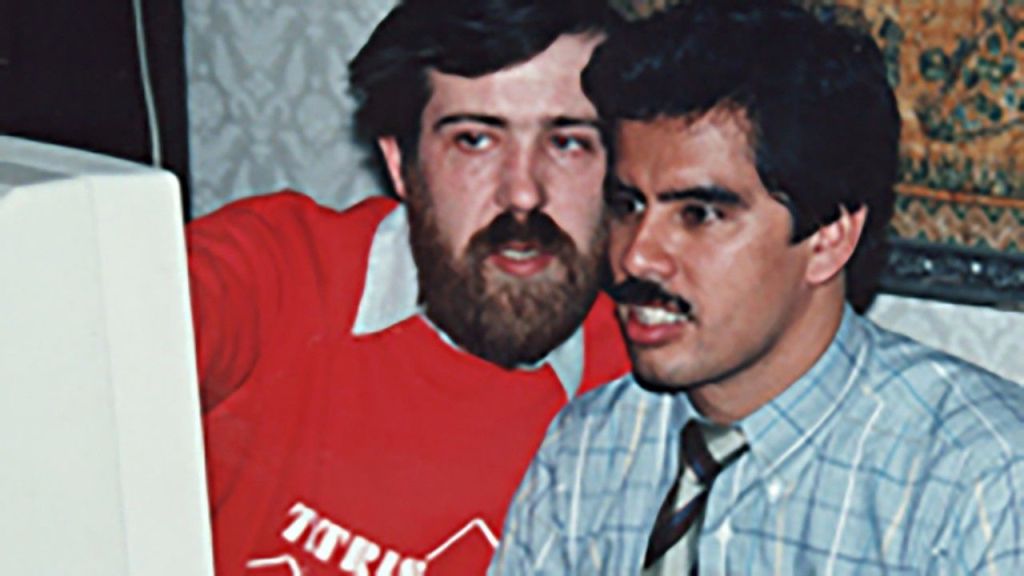

Into this chaos flew a Dutch game designer named Henk Rogers, the man who developed Japan’s first commercially successful RPG, Black Onyx. He had seen Tetris at a trade show and become obsessed. Enlisted by Nintendo to secure the handheld rights, Rogers made an incredibly bold move. He flew to Moscow in February 1989 on a tourist visa, navigated the intimidating Soviet bureaucracy, and marched right into the offices of ELORG, uninvited.

The Soviet officials were shocked. They had no idea console versions of Tetris were already being sold, as they believed they had only licensed PC rights. Rogers, a fellow game designer, succeeded where suits had failed. He built trust. He formed a genuine friendship with the game’s creator, Pajitnov. And, alongside Nintendo’s Howard Lincoln, he secured the exclusive, iron-clad worldwide handheld rights for Tetris.

But Rogers’ true masterstroke was his recommendation when he returned. He argued passionately to Nintendo of America to not sell Tetris separately. Pack it in with every single Game Boy in North America. His reasoning was pure, unadulterated genius. As he famously argued, Super Mario Land would sell the Game Boy to Nintendo fans. But Tetris? Tetris would sell the Game Boy to everyone else as well. It would sell it to parents, to college students, to business travelers, to grandparents. It was a universal puzzle game, with a perfect addictive loop that transcended age, language, and culture and he was right. This single decision transformed the North American launch in 1989, into a cultural event. Tetris was the key that unlocked the adult market, something no other game could have done. It made the Game Boy a Walkman, an essential personal accessory for the 90s.

The Playground Connection

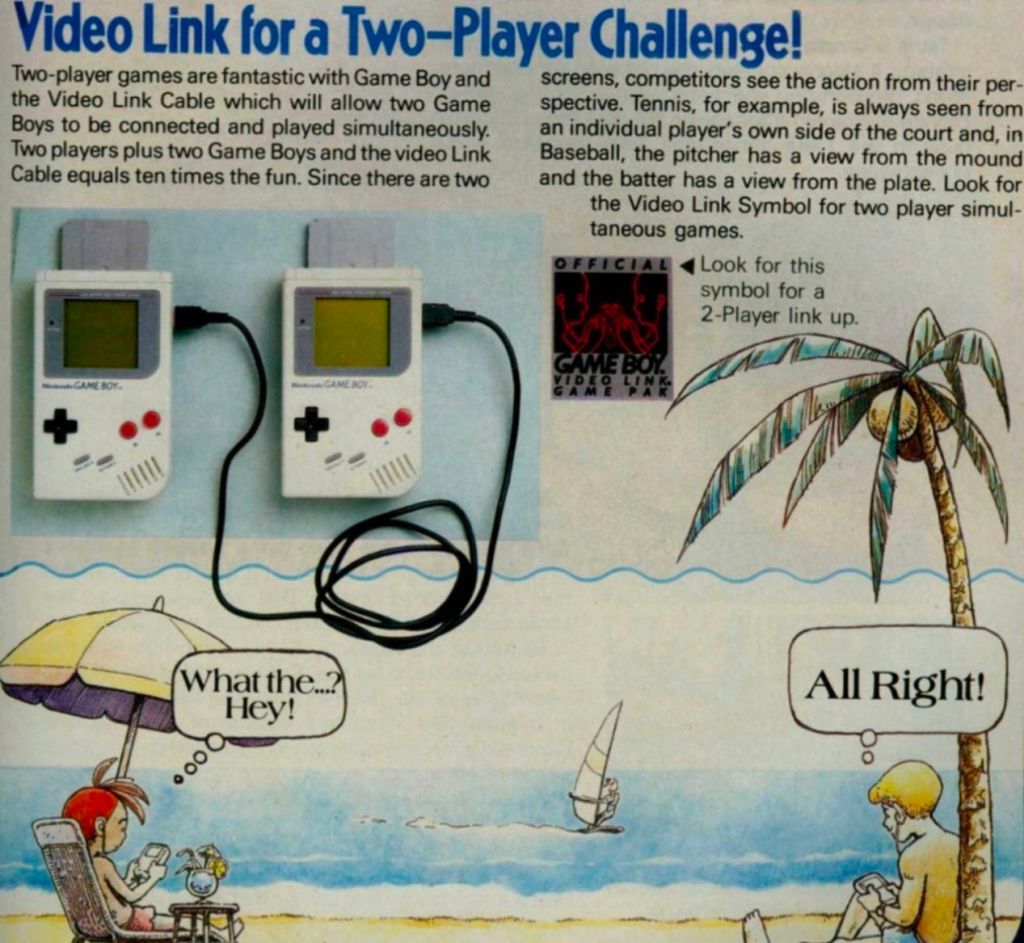

But there was one more piece of Gunpei Yokoi’s puzzle. He knew that the old handhelds were fundamentally solitary, isolating experiences. The Game Boy would be different. From day one, every unit had a port on the side for the Video Link Cable, a peripheral Nintendo pushed hard in its launch ads. Years before Pokémon made it a global phenomenon, this cable was our first taste of connected handheld gaming.

In 1989, this was all about head-to-head competition. The launch lineup of Baseball and Tennis both supported it. The Nintendo Power preview for Baseball highlighted its coolest feature: the pitcher had a view from the mound and the batter had a view from the plate. No split-screen. Just two players linked by a wire, each in their own world, locked in digital combat.

This was revolutionary. It transformed the Game Boy from a personal device into a social one. It was the fuse that lit the fire of playground competition. And Tetris, once again, was the showcase. Linking two Game Boys for a head-to-head Tetris match, sending garbage lines to your friend and watching them panic, was an experience you’d gloat about for weeks after. It was the killer app, the feature that made you grab your friend by the shirt and tell them they had to get a Game Boy too.

The Walkman of a Generation

The Game Boy wasn’t just a successful product, it ended up defining an entirely new market. Nintendo did this not by having the flashiest tech, but by having the smartest. The Game Boy was born from a deep, profound understanding of the user. It correctly identified the non-negotiable pillars of portability. It had to be affordable enough for a parent to say yes. It had to be durable enough to survive a childhood’s worth of drops and tumbles. And most critically, it had to have a battery that lasted. That monochrome screen wasn’t a flaw, it was a deliberate, masterful sacrifice made in service of that greater, more important goal.

When that user-centric design was combined with the strategic masterstroke of the Tetris bundle, the result was more than a successful product. It was a cultural atom bomb. It defined portable gaming for an entire generation. The Game Boy wasn’t just a toy. It was a companion. It was the gray brick that went with us everywhere, its familiar bling on startup a comforting sound. It was the revolution we were promised, a revolution that laid the foundation for the next thirty years of gaming. And in 1989, it truly, finally, put the whole world in our hands.

Mag Coverage

Nintendo Power #8, Sep/Oct 1989

Leave a comment