A Fallen Hero

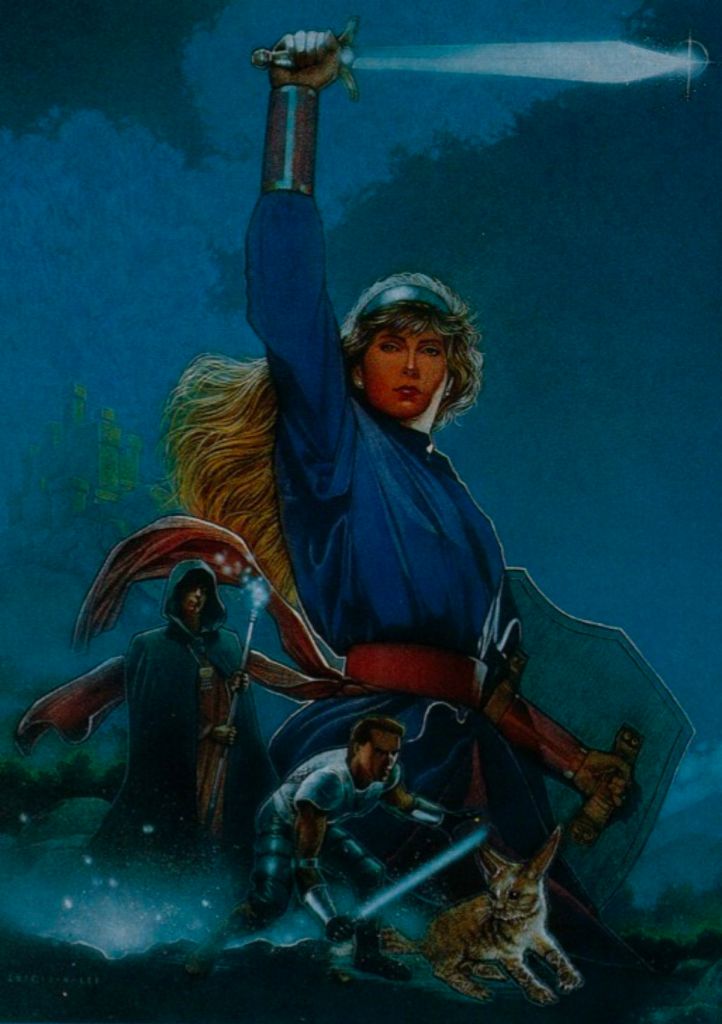

The year is 342 of the Space Century. The three planets of the Algol solar system, once a beacon of peace, choke under the iron-fisted rule of the tyrant King Lassic. His regime is absolute, his power unquestioned. On the streets of Camineet, a young woman named Alis watches as her brother, Nero, is cut down by Lassic’s monstrous foot soldiers. His death lights the rebellion as Alis vows to avenge her brother’s death. Armed with nothing more than her brother’s sword and a burning vengeance, she sets out to find allies to help her topple and empire.

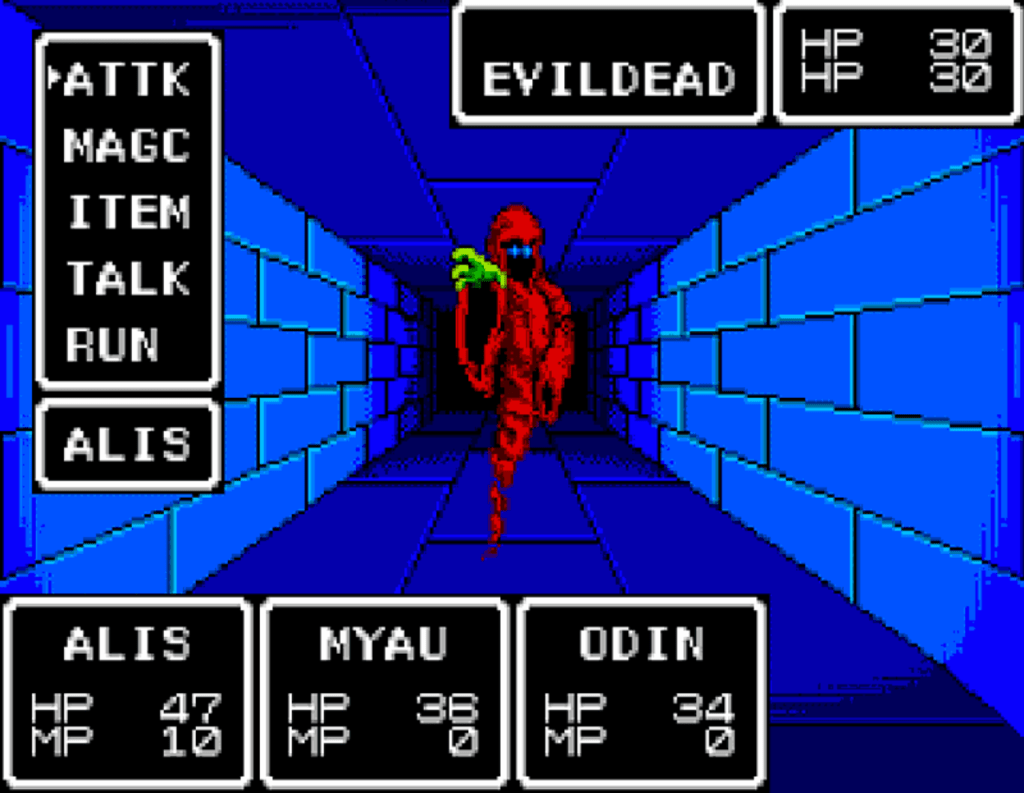

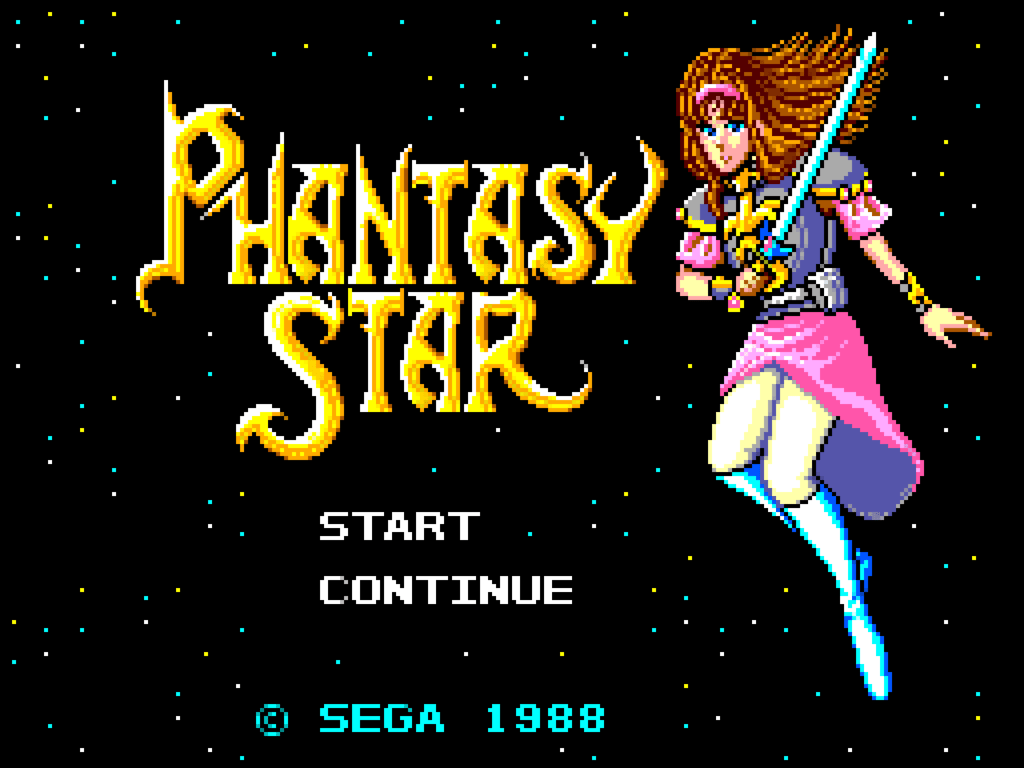

There are moments etched into our memories that we’ll never forget. Phantasy Star running on a Sega Master System for the first time in 1989 has to be one of the most shocking. In a world that had just woken up to Dragon Warrior, defined by the chirpy, top-down simplicity of its thees and thous, Phantasy Star was something of a revolution. When you found that first dungeon and the CRT TV dissolved, not into a flat map, but into a tunnel. A tunnel that moved. You stared, mesmerized as the walls streamed past in a smooth, hypnotic rush. This wasn’t just a game. It was a glimpse of the future, a technological flex that our little 8-bit minds could barely comprehend.

Engineering the Impossible

To understand Phantasy Star is to understand Japan’s 8-bit battlefield in 1987. Nintendo’s Famicom wasn’t just a market leader. It was a juggernaut that held near-total market saturation, its library dominated by the twitch-based immediacy of arcade platformers and shooters. Deep, narrative-driven experiences were largely confined to the niche PC market. But an RPG explosion was happening on the Famicom, led by the popularity of Dragon Quest. Sega, by contrast, was the eternal underdog.

Their Mark III console, struggling with a meager market share in Japan, was by nearly every technical metric the more powerful machine, but it was losing the war for hearts and minds. Sega’s management knew they couldn’t win by playing the same game. Witnessing the RPG phenomenon on their rival’s hardware, they knew they needed their own exclusive, high-quality title in the genre to prove the viability of their own console. This wasn’t just about releasing another game. It was a calculated strategic maneuver.

A directive was issued to their internal teams to create games that were demonstrably impossible on the Famicom. Phantasy Star was engineered from the ground up to be that impossible game. It was a technical salvo designed to highlight the superiority of Sega’s hardware. It was a strategy of pure technological one-upmanship, and it would come to define the Sega brand for years.

The Sorcery of Yuji Naka

At the very core of Phantasy Star’s identity were those groundbreaking first-person dungeons. This was the work of a young programming genius named Yuji Naka. He had seen Western RPGs like Wizardry with their tiny, windowed 3D, and he wasn’t impressed. Naka’s ambition was to shatter that limitation. He wanted a full-screen, smoothly animated 3D effect that would immerse the player completely and feel technologically superlative.

His first attempt was a technical marvel but a design disaster. It ran so fast that playtesters compared it to a high-speed shooter, inducing severe motion sickness. The team was also faced with a second, equally critical problem. The hand-drawn animation frames required for the dungeons were too massive. They would have consumed the entire 4-Megabit cartridge, leaving no room for the rest of the game. The team had two distinct, seemingly unrelated, problems. An engine that was too fast and art data that was too large.

The solution to both emerged from a single, elegant piece of programming. Naka implemented a real-time compression algorithm, storing the dungeon graphics in a compressed format. As the player moved, the Master System’s processor had to decompress this data on the fly before rendering it. This constant processing load acted as a natural brake, slowing the engine down to that smooth, deliberate, and perfectly paced forward momentum we all remember. That iconic dungeon-crawling feel was a happy accident, born from solving a critical memory problem.

Pixelated Planets

With the technical foundation secured, the team’s lead artist, Rieko Kodama, was free to pursue an artistic vision that was as revolutionary as the code. As the main graphic designer, she was responsible for the game’s entire visual identity. Kodama’s primary goal was to create an experience that felt utterly distinct from the traditional high-fantasy castles and dragons of other RPGs of the time. The result was a deliberate and iconic fusion of medieval fantasy and science fiction. We explored ancient castles, then boarded spaceships to travel to other planets. We saw knights in armor wielding laser guns. It was a science-fantasy blend that immediately set the game apart.

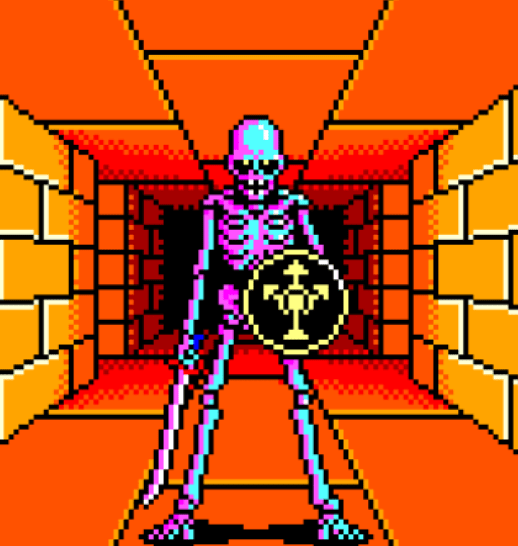

Nowhere was this visual superiority more apparent than in the battle scenes. Remember Dragon Quest or Final Fantasy on the NES? They gave us small, static monster sprites against stark black backgrounds. Phantasy Star delivered enormous, vibrantly colored, and fully animated enemies. These creatures lunged, bit, and clawed. They felt dangerous. And they did it all against detailed, scenic backdrops that reflected your location, from lush plains to beaches with animated waves.

This sense of scale was woven directly into the gameplay. The ability to travel between the three distinct planets of the Algol star system gave the game a scope that was simply unprecedented. It wasn’t just a palette swap as each world felt distinct. You started on the green, Earth-like Palma, the seat of Lassic’s power. You then had to find a spaceship to blast off to Motavia, a scorching desert planet baking under the Algol system’s sun, populated by Jawa-like scavengers and giant ant lions. Finally, you reached the frozen, desolate ice planet of Dezoris, a world of deep caves and hostile climates. This planetary travel wasn’t a gimmick. It was a core part of the epic’s pacing and made the universe feel vast and lived in.

A Heroine’s Vengence

For all its technical and artistic flair, Phantasy Star’s most enduring innovation might be its narrative. In 1987, the JRPG landscape was defined by stoic male heroes. The creation of a strong, plot-driving female lead, Alis Landale, was a truly revolutionary act. This was a deliberate choice championed by Rieko Kodama herself. She wanted a character who would challenge stereotypes and with whom female players could empathize. Alis wasn’t a blank slate. She wasn’t a princess waiting for rescue. She was the driving force behind the story.

Unlike the generic save-the-world quests of its competitors, Phantasy Star’s story is anchored by that deeply personal motivation. The game opens with one of the most shocking scenes in 8-bit history up to that point, with Alis witnessing the brutal murder of her brother. Her journey begins not as a quest to fulfill a prophecy, but as a personal and relatable quest for revenge. She takes the initiative, she recruits her companions, and she drives the plot forward with her own will. This focus on character extended to the entire party.

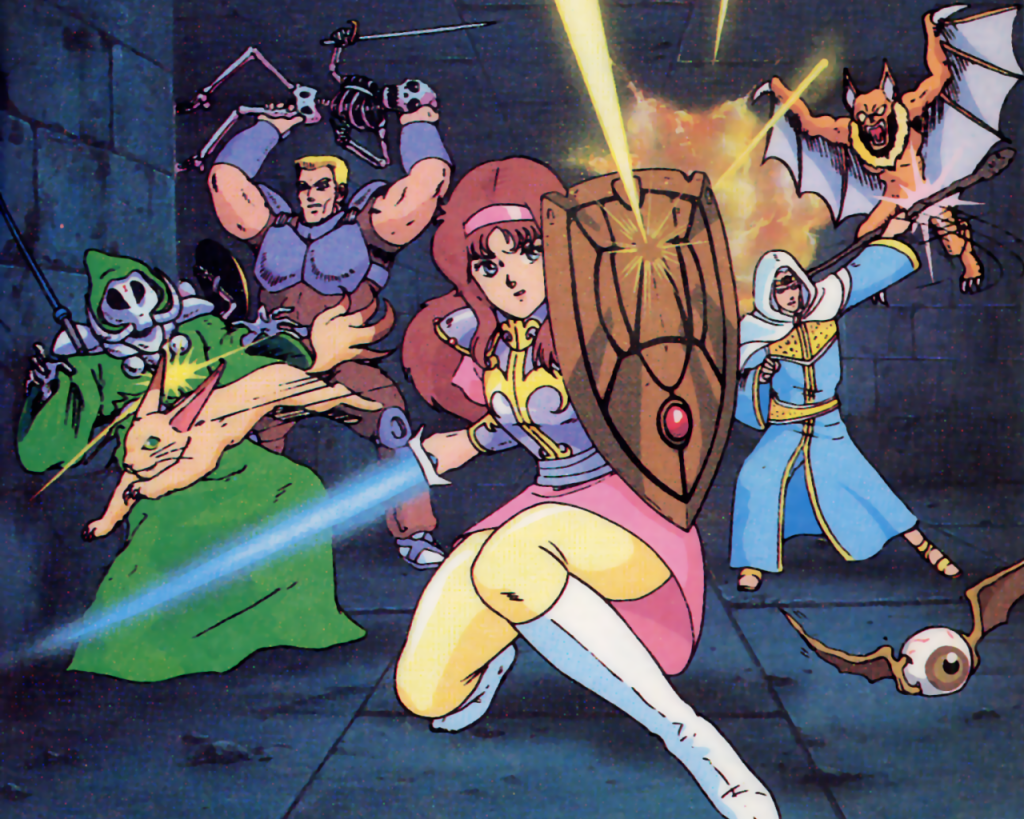

While Final Fantasy offered a customizable party of nameless warriors and the original Dragon Quest was a solo affair, Phantasy Star gave us a cast of pre-defined characters. They weren’t just classes. They had names, motivations, and a stake in the story. There was the hulking warrior Odin, a classic strong-man trope but one who joins Alis out of his own sense of duty. There was the timid but powerful esper Noah, whose magic was essential for survival.

And then, there was Myau. Myau was a talking, winged cat who was also a critical party member, a mascot, and your key to finding the all-important ship. This talking animal wasn’t just a cute sidekick. He was a refugee from another world, a victim of Lassic’s regime, and his personal quest intertwined with Alis’s. They felt like a real team, a band of rebels united against a common foe, not just four avatars you moved around a map. This character-driven party dynamic would not become the JRPG standard for years, yet Phantasy Star had it in 1987.

The Algol Declaration

Phantasy Star was the total package. It was a holistic product where Naka’s code, Kodama’s art, and Alis’s quest, served a larger, strategic goal. The 3D dungeons showcased the Master System’s superior CPU. The large, animated battles and rich color palette were a testament to its more capable video hardware. The epic, multi-planetary story and its defined, mature protagonist created a narrative depth that felt a generation ahead of its time. It was, feature for feature, a direct refutation of the established JRPG formula which relied on heavy stats and fantasy tropes to lure gamers into their worlds.

Its commercial success was solid enough on its home turf to guarantee a sequel, and that sequel would become one of the foundational titles of the 16-bit era. Phantasy Star II on the Sega Genesis took every idea from its 8-bit progenitor and exploded it onto a grander scale. The defined party, the science-fantasy setting, the personal, tragedy-fueled plot, and the sprawling multi-planetary adventure all started here. It set the template for one of Sega’s most beloved and enduring franchises.

This was so much more than just a game. It was a declaration. It was Sega planting a flag and showing the world what its hardware could do when pushed to the absolute limit. It set new standards for presentation and storytelling that would become staples of the 16-bit era. It didn’t just build a world. It built a universe, and its revolutionary echo can still be felt today.

Leave a comment