It’s a Secret to Everybody

In the chaotic fall of 1989, you had to squint real hard to see Sega’s fading Master System. The noise was deafening, a cacophony from new machines all screaming for your allowance. Sega’s own 16-bit Genesis was the new cool kid on the block, promising arcade-perfect conversions. The TurboGrafx-16 was dangling the futuristic carrot of CD-ROMs and Japanese imports. And in our backpacks, the handheld war had begun, a battle between the practical, pea-soup green of the Game Boy and the dazzling, battery-devouring, sprite-scaling, color of the Atari Lynx. If you were one of the few who owned a Master System, it hadn’t seen play in months as it was also quickly being outclassed by Nintendo’s third parties who had begun to master the NES.

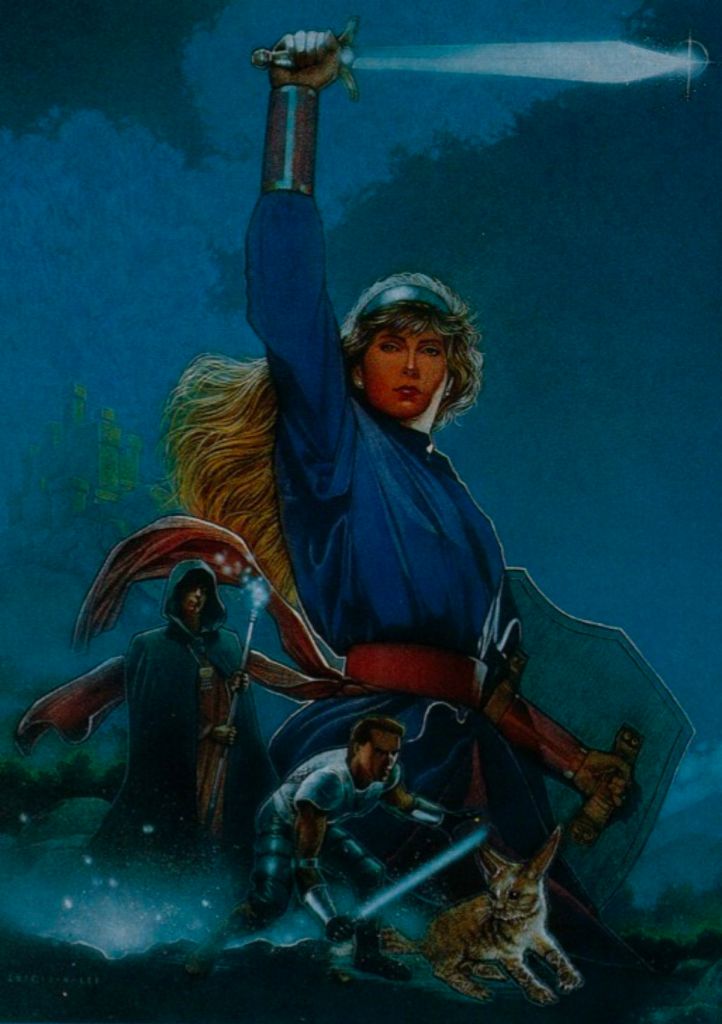

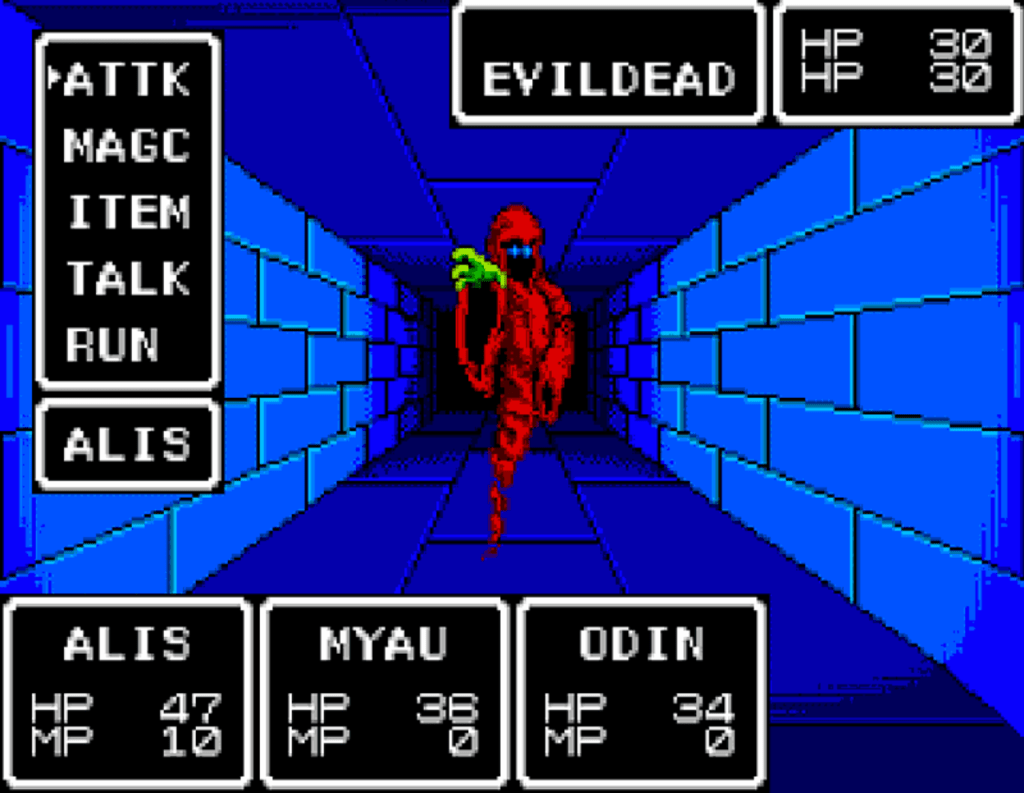

And then there it was, a beacon in the noise that immediately drew your attention as soon as you hit the ProViews section of the latest issue of GamePro. Phantasy Star, with its stunning, painterly, backdrop of a woman named Alis holding a sword aloft backed by her companions Noah, Odin and Myau. You had to have it! That first moment when you finally got to jam that huge 4-meg cartridge into your Master System the entire house went silent as you fell into the game’s deep and colourful adventure. First-person 3D dungeons, moving at a blistering speed, a three-planet solar system to explore and a female protagonist. This wasn’t just a Dragon Warrior knock-off, this was a next level RPG. How could this game, which felt like it could stand toe-to-toe with anything on the PC, exist on a console that everyone was telling you was already dead?

As if to prove Phantasy Star wasn’t a fluke, Sega also delivered Wonder Boy III: The Dragon’s Trap. A cartoonish adventure showcased in the very same GamePro back-to-back with Phantasy Star. But playing it revealed a work of genius. Starting as Wonder Boy, you are quickly cursed and transformed into the fire-breathing Lizard-Man. This wasn’t a punishment, it was the key. The game’s world was a massive, interconnected puzzle and each boss you defeated cursed you into a new animal form, each with their own special abilities. It was colorful, charming, and impossibly clever, a masterclass in adventure platforming that stood shoulder-to-shoulder with anything on the NES.

Master System Under Siege

These games felt like a miracle because the 8-bit Master System was being crushed from every conceivable angle.The most obvious pressure came from above: the 16-bit future. At the Summer Consumer Electronics Show, Sega was sizzling with its own successor, the Genesis. The system was coming in hot as the console was built around a powerful Motorola 68000 processor, the very same high-end CPU found in Sega’s arcade cabinets. EGM trumpeted the arrival of a staggering fifteen launch titles, led by the muscle-bound pack-in Altered Beast and the arcade-perfect port of Ghouls ‘n Ghosts. All of Sega’s marketing muscle, all of its hype, was being poured into this sleek black box. At the same time, NEC’s TurboGrafx-16 was wooing the hardcore tech-heads. Its CD-ROM add-on was the stuff of science fiction, a peripheral that promised over 2,000 times the storage of a cartridge! This wasn’t just a bigger game, it was a portal to a new dimension of real music, voice acting, and cinematic cutscenes.

While the 16-bit machines were squeezing from the top, the battle for our backpacks was squeezing the Master System from the sides. The handheld war exploded into the headlines and it was a perfect clash of philosophies. In one corner stood the Atari Lynx. Billed as a Pocket Arcade, this thing was a technological beast. It had a stunning, full-color backlit LCD screen capable of displaying over 4,000 colors. Its 16-bit hardware could scale and rotate sprites, a feat that even the new 16-bit home consoles couldn’t manage. It was, without exaggeration, an arcade in your pocket. In the other corner was the incumbent, Nintendo, with the Game Boy, a device that seemed almost primitive by comparison. This compact video system was a study in lateral thinking with withered technology. It was a chunky, heavy gray brick. Its dot-matrix screen was four shades of what we could generously call pea-soup green, a blurry mess that ghosted with any fast-moving sprites.

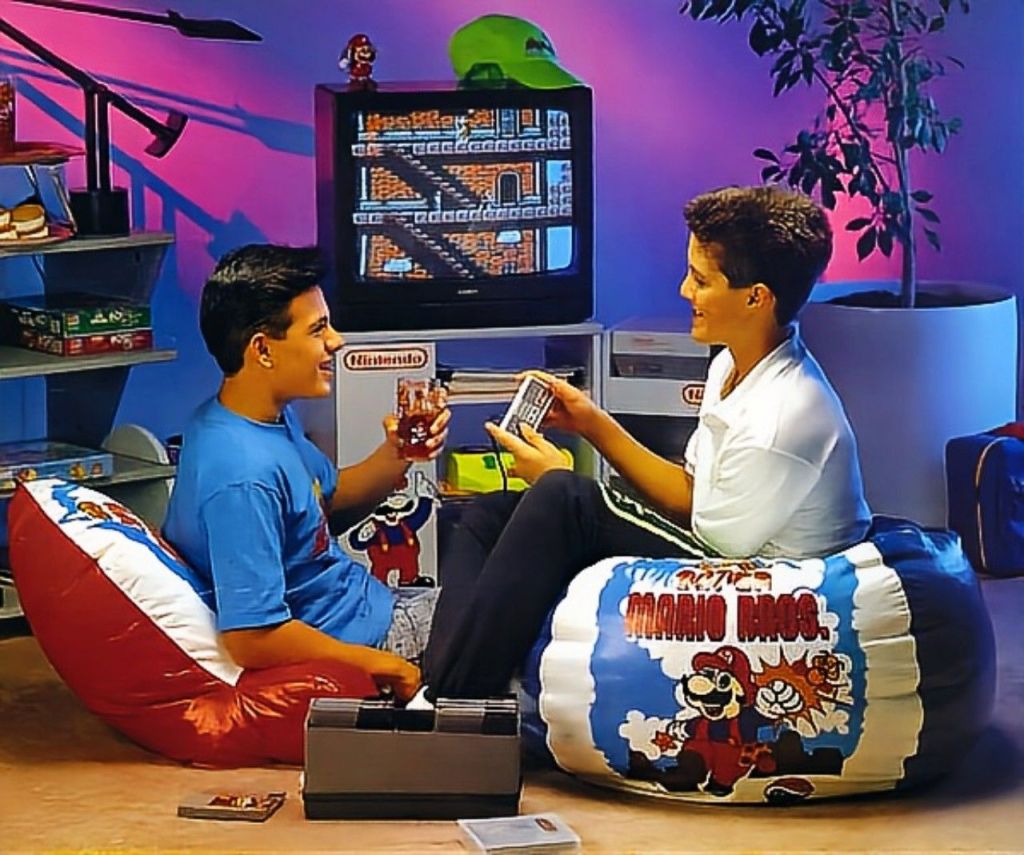

Finally, the Master System was being squeezed by the 800-pound gorilla that had been sitting on its chest for years. Nintendo’s dominance with the NES was absolute. It wasn’t just a console, it was a cultural landmark, a fixture in one of every three American homes. But Nintendo wasn’t planning on just sitting around releasing games in the face of the 16-bit competition coming down the pipeline. The company was planning to expand its horizons, partnering with AT&T to turn the NES into a home communications terminal for buying stocks and airline tickets. They would release the NES Satellite, a wireless four-player adapter, because of course all your friends had an NES too. While Sega was fighting for its life, Nintendo was planning for total world domination.

The Master System was faltering as third-party support for Sega’s Master System was quickly drying up. Tonka, handling US distribution, was struggling to get anyone on board. The console was commercially adrift, ignored by the future, overshadowed by the handhelds, and thoroughly crushed by its rival. While we might have looked towards Ultima IV for the next Master System hit, the writing was on the wall as the system would fade out of our consciousness as we moved into the blistering hot Christmas season of 1989.

The Battle for Our Backpacks

While the 8-bit home console market saw the Master System struggling, a new battle was brewing in the burgeoning handheld arena, where the Atari Lynx and Nintendo Game Boy were about to clash in a contest of power versus practicality. On paper, the Lynx was a public execution of the Game Boy. But this technological prowess came at a steep cost. The Lynx debuted at a wallet-crushing $149.95. Worse, it was a six AA battery-devouring beast that offered glorious, fleeting moments of color for a mere four to five hours. While Game Boy owners were still on their first set of batteries, a Lynx owner was already raiding every remote control in the house for fresh power. The Game Boy, at $89.95, was the antithesis. It was built like a tank, it felt perfect in your hands and most importantly, it could run for over 20 hours on just four AA batteries.

The industry itself saw the outcome from a mile away. The experts all predicted the Game Boy would be the winner of the portable console war. But the masterstroke no one could have predicted was Nintendo’s incredible luck to secure Tetris as the Game Boy pack-in after it had been smuggled out of the Soviet Union by Henk Rogers. This block-maneuvering puzzle solver was the single most addictive piece of software ever created. It needed no complex sprites, no scrolling backgrounds. It was pure, uncut addiction, a perfect match for the hardware. Hooked up with the Video Link cable, Tetris became the ultimate two-player showdown, a social phenomenon played on school buses, in backseats, and under desks across the world. The war for our pockets was over before it began.

8-bit innovation

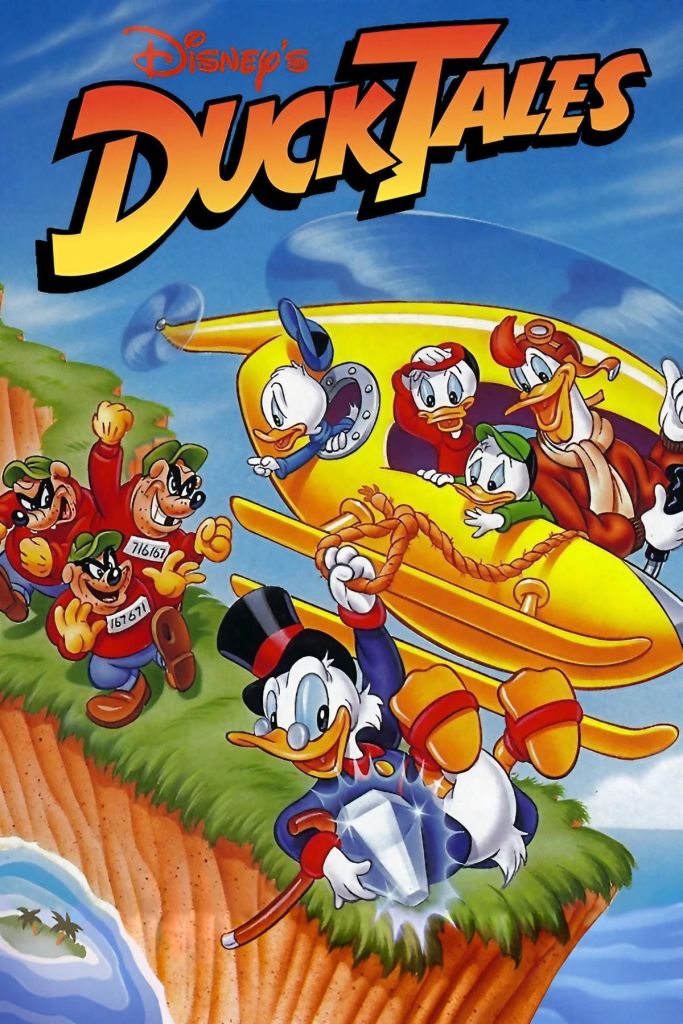

And yet, after all this talk of 16-bit processors, CD-ROMs, and color handhelds, where was the real, undisputed king of 1989? Nintendo was still sitting firmly on its 8-bit throne. The great twist of this next-gen invasion was that the NES was in the middle of its golden age. Its third-party masters, chief among them Capcom, were putting on an 8-bit clinic and their poster child was DuckTales.

Based on the stellar afternoon cartoon, this was not a cheap licensed cash-in. This was a top tier platformer that represented the absolute pinnacle of 8-bit design. Playing as Scrooge McDuck, we were given the pogo-cane, one of the greatest mechanics in gaming history. You could use it to smash blocks, attack enemies, and bounce across hazardous gaps. It added an incredible layer of skill to the game’s platforming. We weren’t just moving left to right. We were bouncing through Transylvania, the Amazon, the Himalayas, and in a moment of pure magic, The Moon. The game was tight, the graphics were vibrant, and the music was a chiptune score that is still stuck in our heads over three decades later. DuckTales was Nintendo and Capcom’s thundering answer to the 16-bit threat. It was a masterpiece that made you feel good about taking a pass on the new consoles when you were in the middle of the most innovative deluge you’d ever seen.

Surfing the Chaos

That was the beautiful, chaotic truth of 1989. It wasn’t the beginning of the end of our 8-bit adventures, but was the first time we truly had a buffet of video game entertainment to choose from. The future was dazzling, with the Genesis and TurboGrafx-16 offering power we’d only dreamed of and, at the other end of the spectrum, our handheld games were on the road with us. In the middle, 8-bit was still here, as the Sega Master System was still producing ambitious masterpieces that rivaled anything on the market.

But the king was still the king. The NES, powered by its unassailable library of classics and upcoming hits like DuckTales, was still the center of the video game universe. We stood at a crossroads, with 16-bit power waiting to be picked up from the store aisles, 8-bit perfection still on our TVs, and the endless, addictive drop of Tetris in our backpacks. It was, quite simply, the best time to be a gamer.

Leave a comment