Dial it Back 100 Years

You’ll never forget that feeling. Quietly heading down to the living room on an early Saturday morning while the rest of the house was still asleep. For one glorious hour it was just you and your magical grey box, the NES. You knew nothing of the 16-bit competitors that had just begun their invasion of your local rental stores, to you video games were Nintendo and Nintendo was video games. You’d jam on your favourite games until your house woke and dragged you into the deluge of weekend errands, family visits and little league sporting events. For the rest of that day, you’d just be trying to survive till you could get back home and sneak in a few more plays before bedtime.

But if you could turn back exactly one hundred years from where you were that morning, you wouldn’t have found flashing screens or digital heroes. You would have found a small wood workshop in Kyoto and a craftsman methodically painting brightly colored flowers onto small stiff cards. The story of how that small card shop grew to become an entertainment giant is not an easy one of triumph. It’s a hundred-year epic of daring gambles, heroic failures, and relentless reinvention that not only created a company, but resurrected an entire industry.

Leave Luck to Heaven

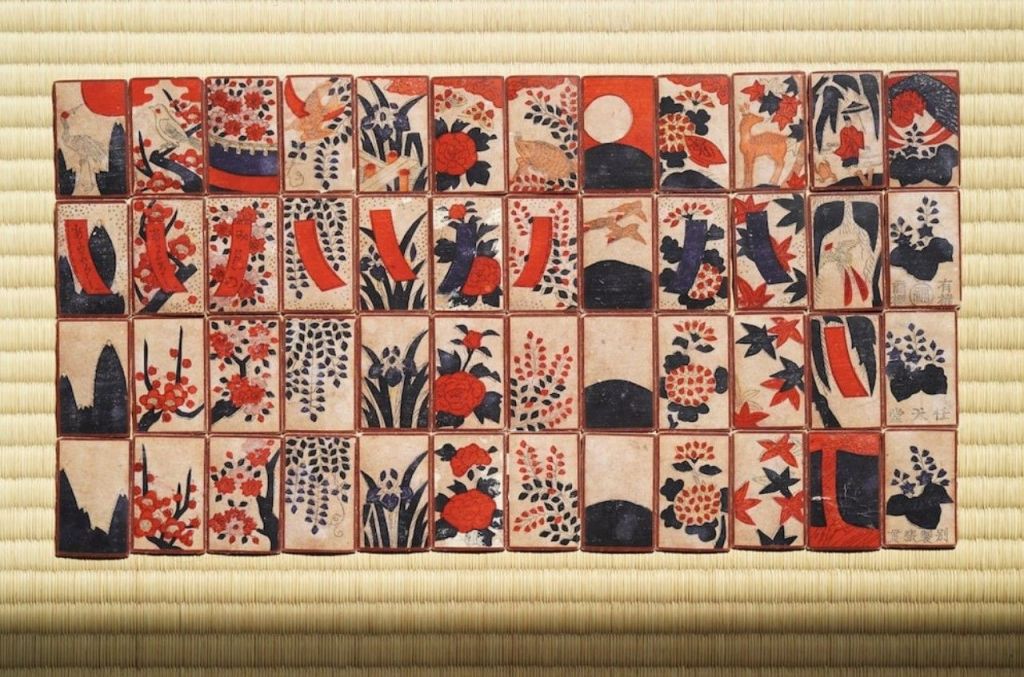

Nintendo’s story begins in 1889, artisan Fusajiro Yamauchi began Nintendo Koppai to make Hanafuda, or “flower cards” by hand. They were not ordinary playing cards. They were works of art constructed from mulberry bark, each of the 48 cards divided into twelve sets representing the months of the year, marked with culturally appropriate flora and fauna. Even the name Nintendo has been taken to mean “leave luck to heaven,” a very fitting motto for a company whose earliest products had been instruments of chance.

Yamauchi was a shrewd businessman. He realized his high-end cards were a niche product, so he did two things. He made a lower-cost line to capture greater market share. Most importantly, he doubled down on the association that made others uneasy. He targeted the yakuza-run gambling houses, which needed a continuous stream of new decks. This pragmatic, if risky, decision initiated a fundamental philosophy of cut throat business acumen that would resound for a hundred years at Nintendo.

This formula worked profitably for decades. During World War II, when Nintendo came close to bankruptcy, they entered into an agreement with the Japanese government to produce playing cards with nationalist slogans on them. Surviving the upheaval of World War II was no small feat and in 1948 the then president of Nintendo, Sekiryo Kaneda, suffered a stroke. Realizing how little time he had left, Sekiryo quickly recruited his grandson, Hiroshi Yamauchi.

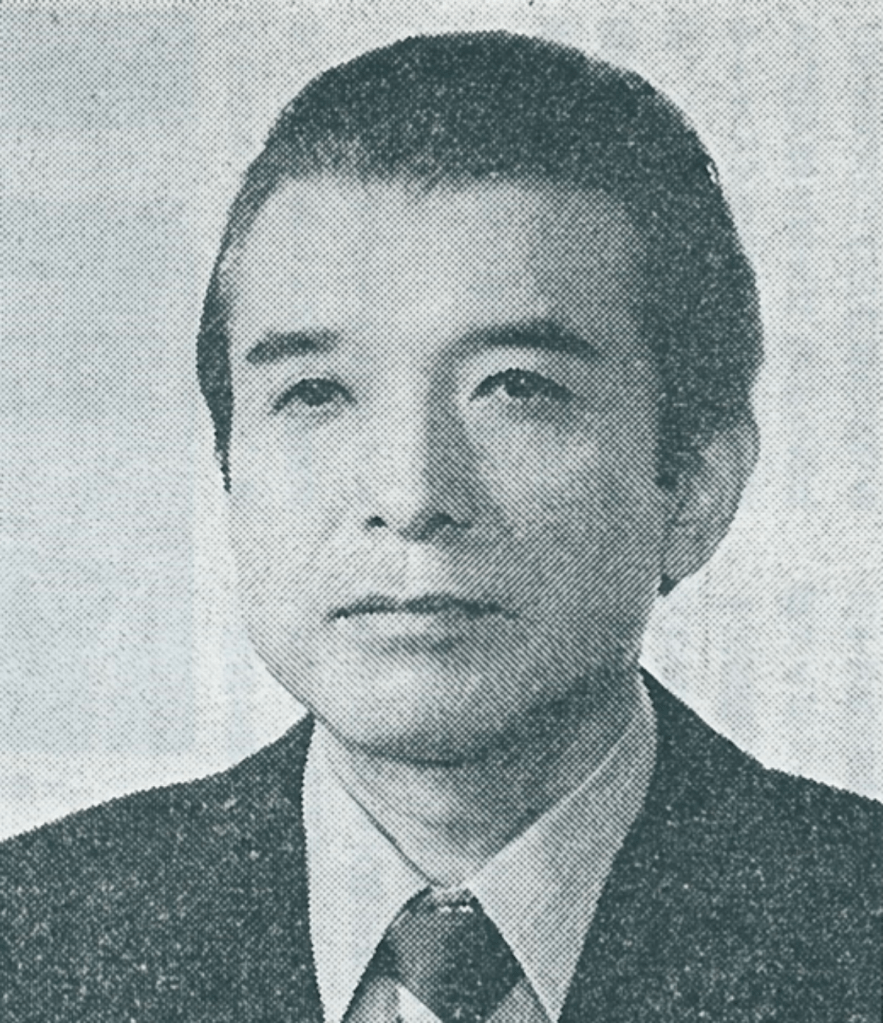

At 21 years old, Yamauchi was forced to drop out of university to take over the family business. Yamauchi agreed but only on the condition that he be the only family member employed at Nintendo, leading to the immediate firing of his cousin. Young, inexperienced, and utterly autocratic, he was greeted with immediate hostility. His response was absolute. When veteran workers struck, he fired every last one of them. He became the final authority on every new product, a notoriously imperialistic boss who made decisions on nothing more than his own intuition.

Yamauchi’s ambitions stretched far beyond cards. After a trailblazing 1959 deal with Walt Disney to put characters like Mickey Mouse on playing cards, Yamauchi realized there was a low ceiling for the playing card industry. Between 1963 and 1968, he launched a series of losing ventures: a taxi company involved in union turmoil, a brand of instant rice that was disgusting, and even a chain of love hotels for married couples. These losses depleted the company’s capital and left it on the brink of insolvency.

Nintendo’s salvation would not come from the boardroom, but from the factory shopfloor. In 1966, Yamauchi had observed a maintenance engineer named Gunpei Yokoi playing with an extendable claw arm that he had built himself at home. Yamauchi was interested, and invited him to turn it into a Christmas toy. The Ultra Hand was a phenomenal success, selling over 1.2 million units and saving the company from the verge of bankruptcy all by itself.

Lateral Thinking with Withered Technology

Yokoi was promoted to oversee a new R&D department, where he developed a design philosophy that would be Nintendo’s secret ace: Lateral Thinking with Withered Technology. The idea was cleverly straightforward but a game-changer. Instead of using expensive, bleeding-edge technology, Nintendo would use low-cost, mature, and highly developed technology in new, creative uses. Fun, in his opinion, was more important than raw power. This philosophy drove a string of hit electronic games in the 1970s, including the Beam Gun line, and ultimately brought Nintendo into the then-thriving market for arcade video games.

The firm’s initial foray into the US arcade business was nearly another disaster. A title, Radar Scope, bombed spectacularly, leaving the new Nintendo of America subsidiary with 2,000 unsold cabinets and near bankruptcy. At a final push, the NoA head requested Yamauchi for a new game to be installed in the older hardware. Since his top engineers were busy, Yamauchi asked a young artist he had hired in 1977, Shigeru Miyamoto.

With his very first chance at creating a game, Miyamoto, guided by Yokoi, made something of a masterpiece out of constraints. He couldn’t count on showy hardware, so he counted on personality, storytelling, and innovative gameplay. That game was Donkey Kong. It was a company-shaking success that saved the American branch and put Nintendo on the global map.

The Trojan Robot

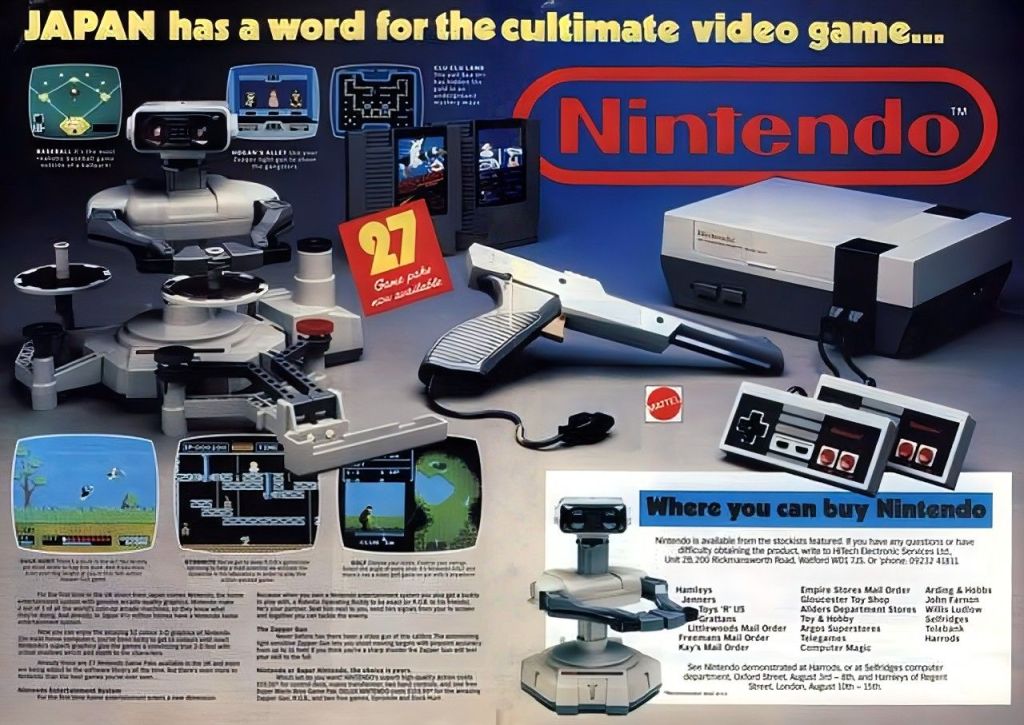

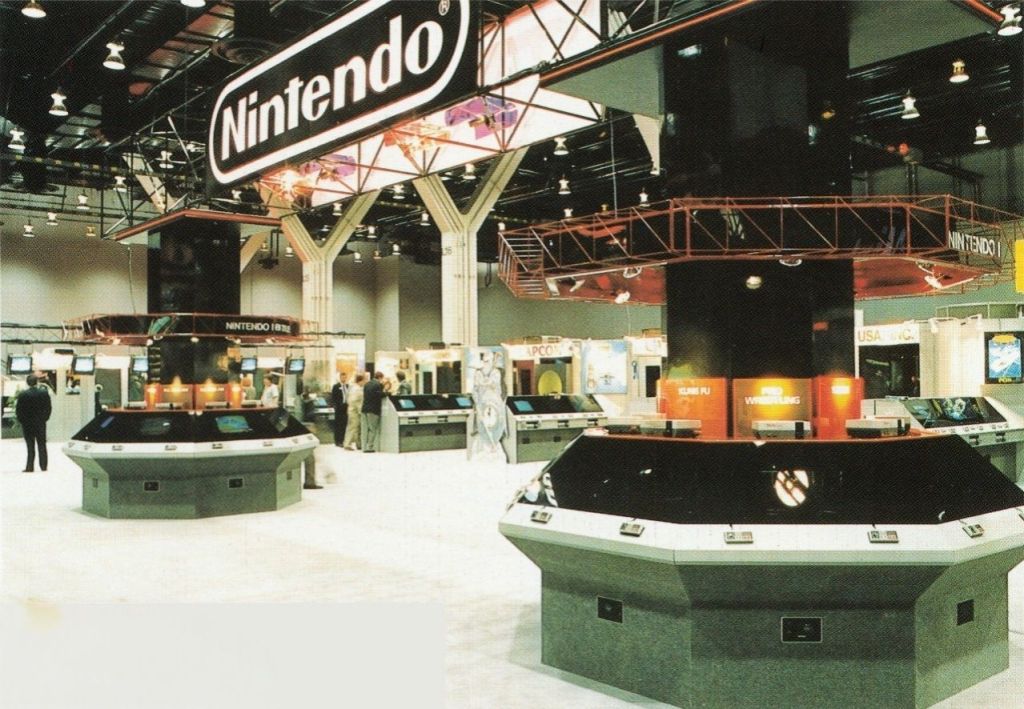

This fusion of Yamauchi’s idealism, Yokoi’s practicality, and Miyamoto’s imagination was the magic sauce that would rocket Nintendo to the top of the arcade world. When Nintendo decided to enter the stagnant American home console market, they didn’t just ride in on some half baked console strategy, they initiated a full out assault on the American toy industry by completely reengineering the Famicom. The toy-like red-and-white color scheme gave way to a sleek, grey, VCR-shaped body, rebranded as the Nintendo Entertainment System.

The NES was meant to look like a serious piece of home electronics, not a toy. But the stroke of brilliance was R.O.B. (Robotic Operating Buddy). This absurd plastic robot, included in the box with the console, was a Trojan Horse that we all fell in love with. By marketing the NES as a new toy system with an interactive robot, Nintendo sidestepped the video game stigma entirely, gaining shelf space in the still-thriving toy sections instead of being relegated to the dying video game aisles stocked with the Atari 2600s and ColecoVisions that nobody wanted.

The gambit paid off, and the NES revived an industry everyone had given up on. Yamauchi refused to make the same mistakes that killed Atari. He took a policy of complete control. Every console and cartridge contained a 10NES lockout chip, a security device which would not allow unlicensed games to play. To get the chip, developers had to agree to Nintendo’s draconian terms. Nintendo manufactured all cartridges, publishers advanced funds, and titles were exclusive for two years. To introduce this new era of quality control to dubious consumers, every licensed game box carried the Official Nintendo Seal of Quality.

Hardware and business plans, of course, are for naught without the games themselves. Shigeru Miyamoto created two that would be cultural touchstones. Super Mario Bros., typically bundled with the console, perfected the side-scrolling platformer and schooled its players in the ways of its controls through brilliant, instinctive design. Then came The Legend of Zelda the following year. A sprawling fantasy based on Miyamoto’s childhood wanderings in the Kyoto countryside. It shifted the emphasis away from achieving high scores and, with the help of a groundbreaking battery-backed save function, enabled enormous game worlds for the very first time on a console.

By 1989, Nintendo had not only survived a whole century of ups and downs, it was the uncontested king in the home console market. The same year, it launched the Game Boy, a perfect embodiment of Yokoi’s withered technology idea, that used a cheap monochrome screen to cut costs and offer prolonged battery life while obliterating its technologically sophisticated color-screen rivals. Yet, at the company’s very peak, a challenger arrived. Sega launched its 16-bit Genesis console, backed by an in your face advertising campaign that roared, Genesis does what Nintendon’t. The first great console war had begun, and the stage was set for Nintendo’s second century.

Forging an Empire

Nintendo’s first hundred years were a vicious cycle of boom, bust, and creative reinvention. Nintendo’s DNA was forged in the hard-nosed risk-taking of a founder who wasn’t shy about negotiating with gamblers to acquire a market. It was tempered in the crucible of defeat by an autocratic leader whose disastrous search for a new identity forced the company to find its authentic calling in entertainment. It built its empire on a different creed that prioritized imagination over brute strength, combining Gunpei Yokoi’s genius reassignment of obsolete technology with Shigeru Miyamoto’s innovative focus on character and game design.

From a Kyoto workshop to a global sensation, Nintendo had outlived not only that but established the rules of a new world. Facing down its first true console war as the company entered its second century of business, leaving luck to heaven looked like as good a bet as any for Nintendo.

Leave a comment