The New Game in Town

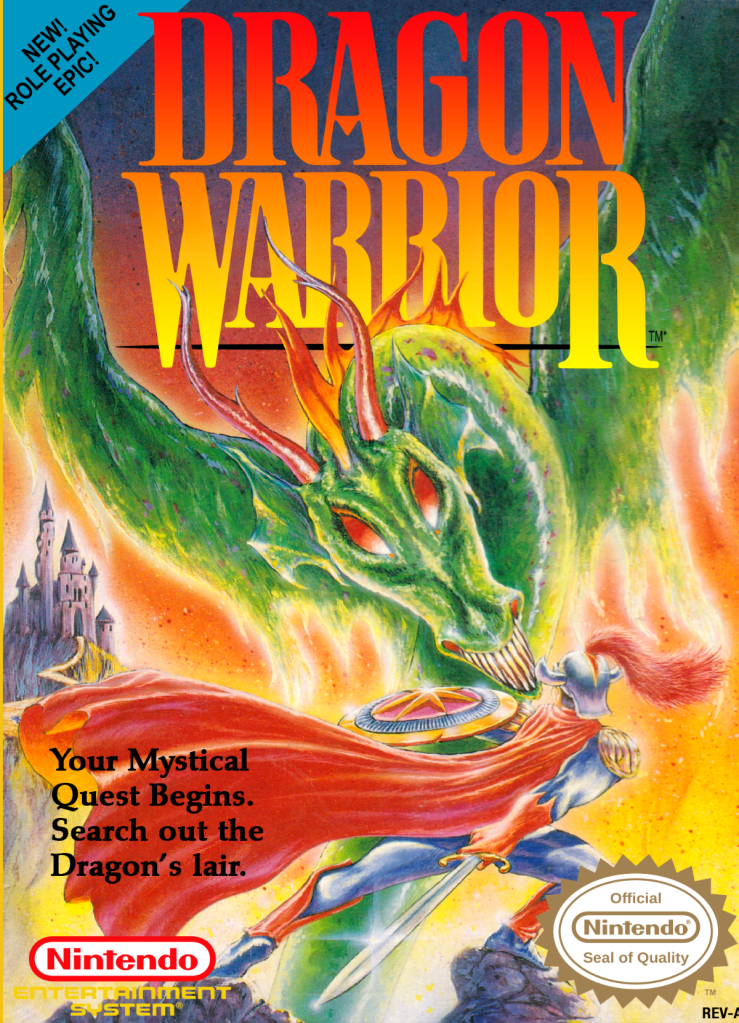

It arrived without warning. Not as a birthday gift or a hard-won prize for a good report card, but as a dense, heavy package in the mailbox one quiet afternoon. You might have forgotten you’d even sent in the subscription card, torn from the back of Nintendo Power magazine, along with fifteen bucks your parents reluctantly parted with. But there it was, an epic looking box titled Dragon Warrior. A knight with a flowing red cape facing down a monstrous dragon, a shadowy castle lay off in the distance. It promised an epic clash, like your favorite sword and sorcery movie from the video store.

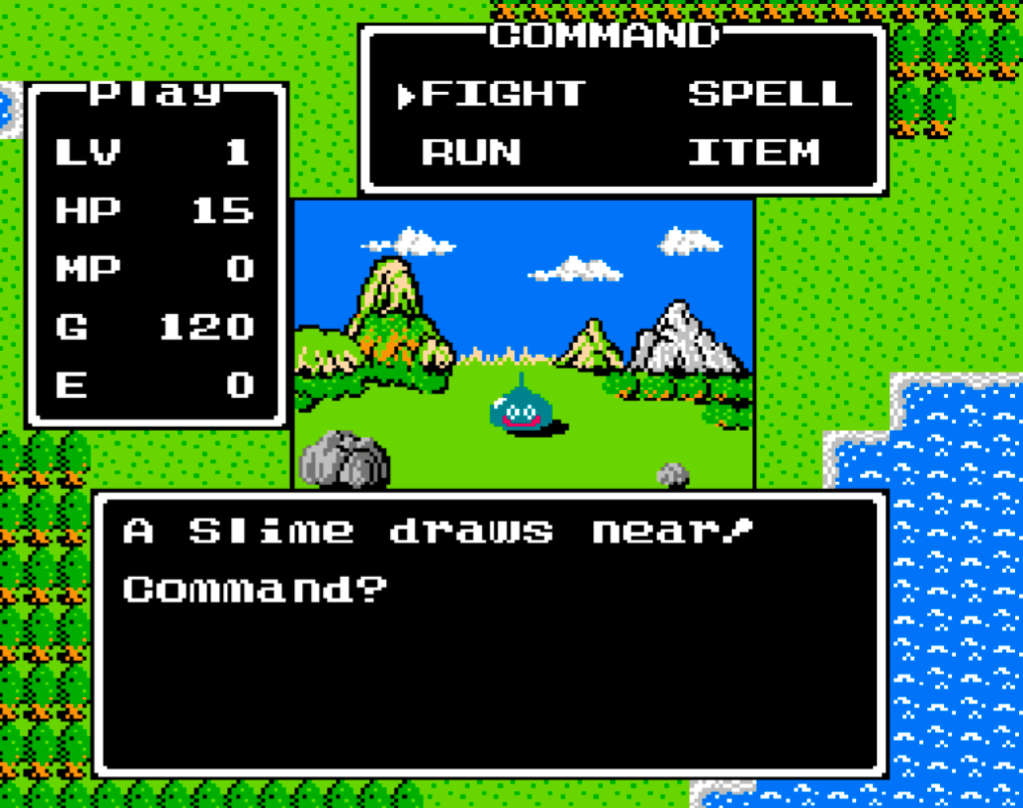

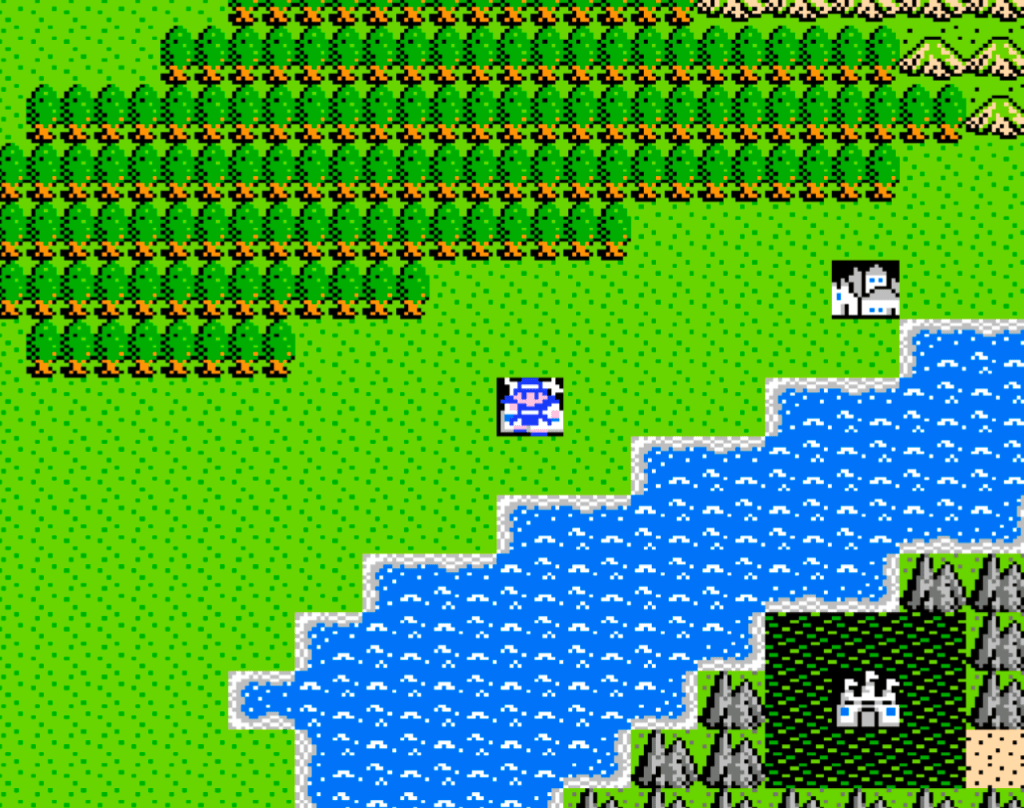

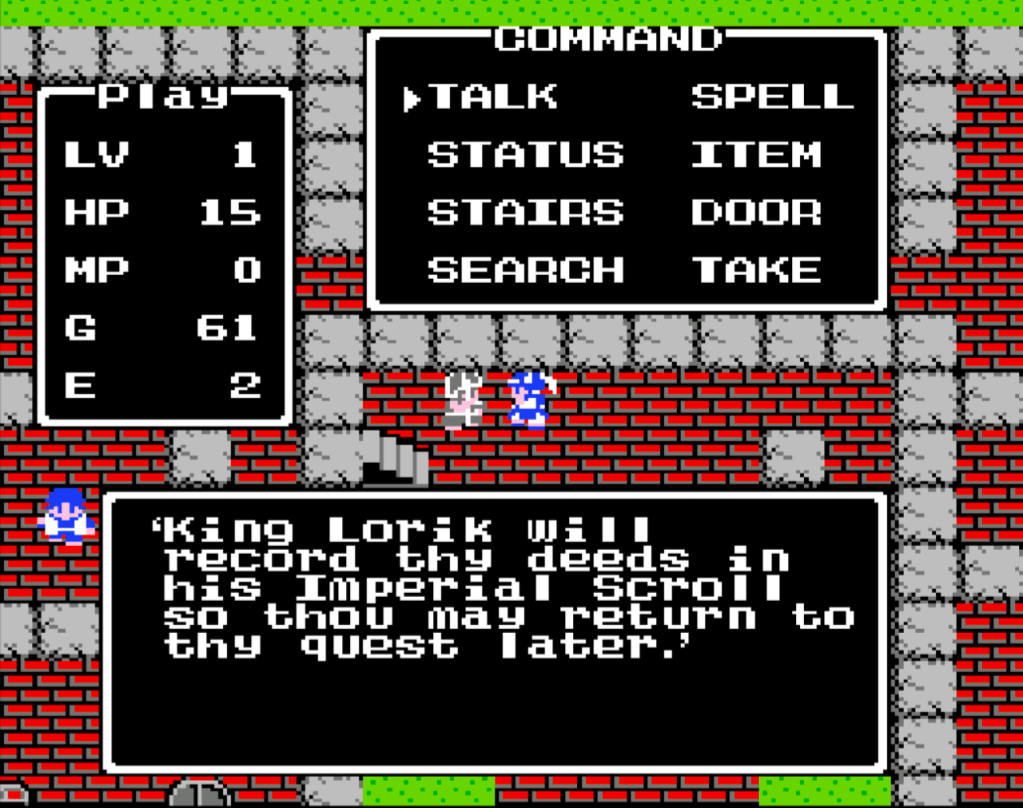

Then you slid the chunky grey cartridge into your NES, pushed it down with that satisfying clack and flicked on the power. There was no instant action, no jumping, no shooting. There was just a guard, standing still. You walked up to him. Nothing happened. You pushed buttons. Nothing. Then, a menu appeared. You selected talk and the guard responded “Save thy money for more expensive armor.” You were presented with a world of text and choices. Your adventure began as you set off by slowly walking across a map until, with a jarring flash, you were fighting a slime! A blue, smiling teardrop that looked like it was drawn for a Saturday morning cartoon.

For a kid raised on the immediate thrills of Contra and Mega Man, this was utterly alien. It was slow, confusing and felt like a bizarre mistake. Little did we know, this strange, free cartridge wasn’t a mistake at all. It was the aftermath of a failed attempt to bring RPGs to the North American console market, a last-ditch effort to offload a million unsold units and one of the most important, accidental, lessons in video game history. We were the unsuspecting students in a grand experiment, and our homework was to learn the strange new language of the RPG.

A CRPG Visionary

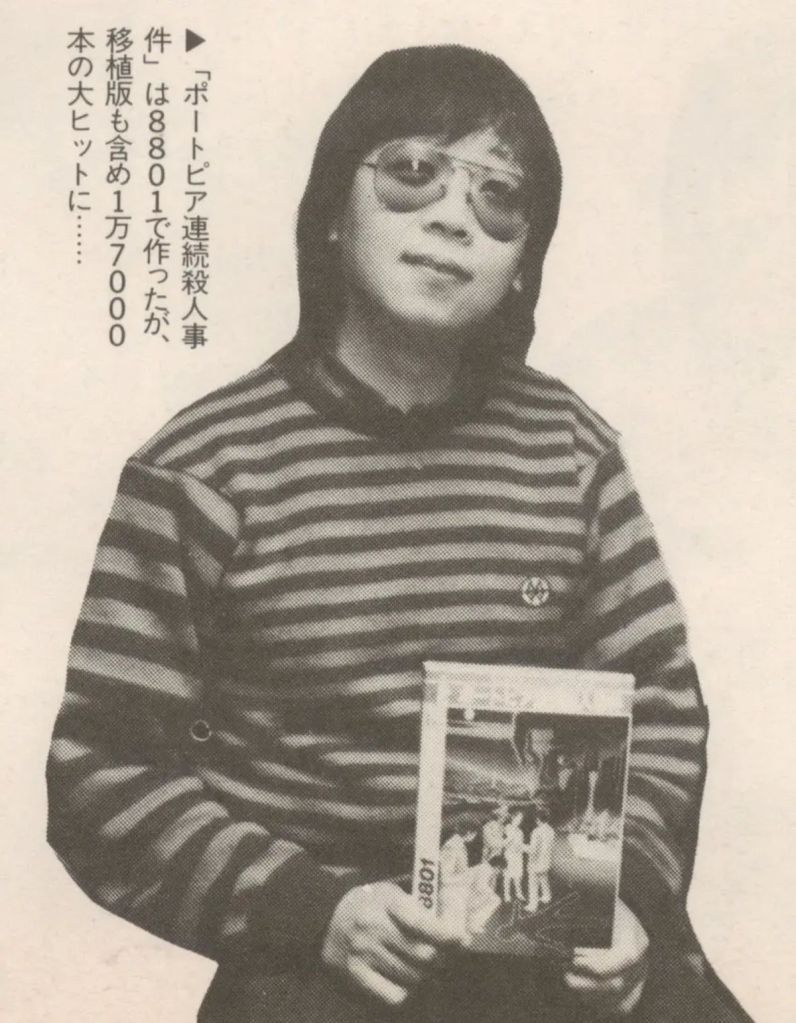

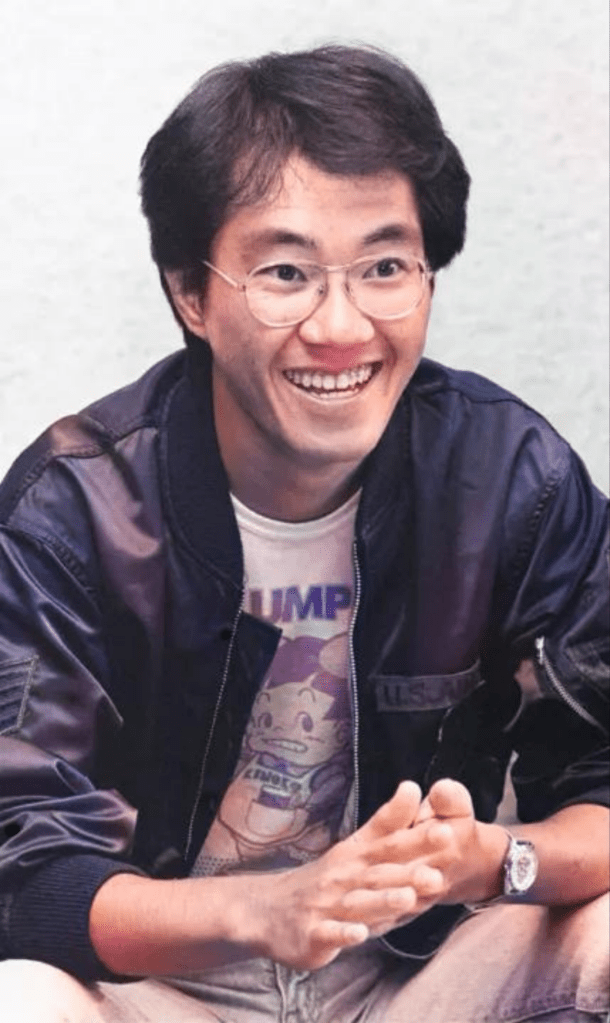

To understand the game that baffled a million North American kids, you have to travel across the ocean and back in time to meet a young man torn between two worlds. Yuji Horii, born on Awaji Island, spent his youth wrestling with a fundamental conflict: he had the soul of a storyteller and the mind of a systems analyst. He dreamt of becoming a manga artist but also possessed a powerful aptitude for mathematics that seemed at odds with his artistic ambition. The internal duality of art versus logic, story versus system, would become the blueprint for an entire genre.

A motorcycle accident after college nudged Yuji away from a traditional career and into freelance writing, landing him with the manga anthology Weekly Shonen Jump. This twist of fate put him on a collision course with the burgeoning microcomputer revolution. Fascinated, he bought his own NEC PC-6001 and taught himself to program, seeing the machine not as a calculator, but as a new medium for storytelling.

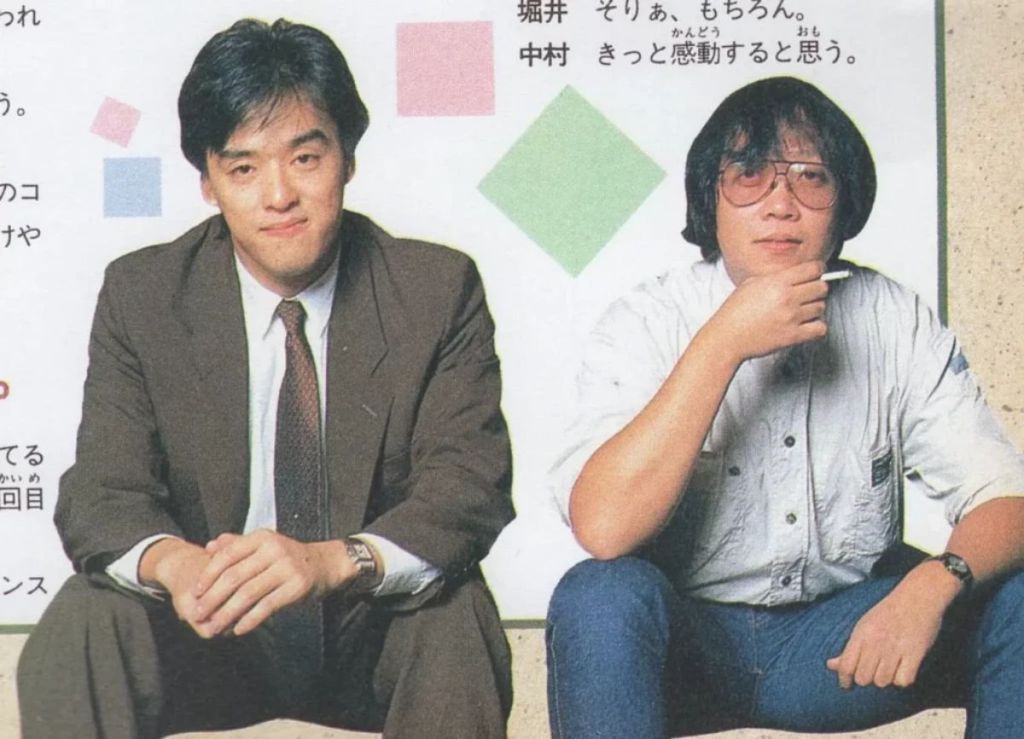

In 1982, a new publisher called Enix, looking to pivot from real estate to the hot new world of video games, held a programming contest to find fresh talent. Yuji, now writing a column for the massive manga magazine Weekly Shonen Jump, was assigned by his editor to cover the awards ceremony. In a move of incredible audacity, he anonymously entered his own homemade game, Love Match Tennis, into the very contest he was supposed to report on. Imagine his shock when he arrived at the Enix office, reporter’s notebook in hand, only to discover his own game had won a top prize. This fateful event not only launched his career but introduced him to Koichi Nakamura, a prodigious high school student who also placed in the finals.

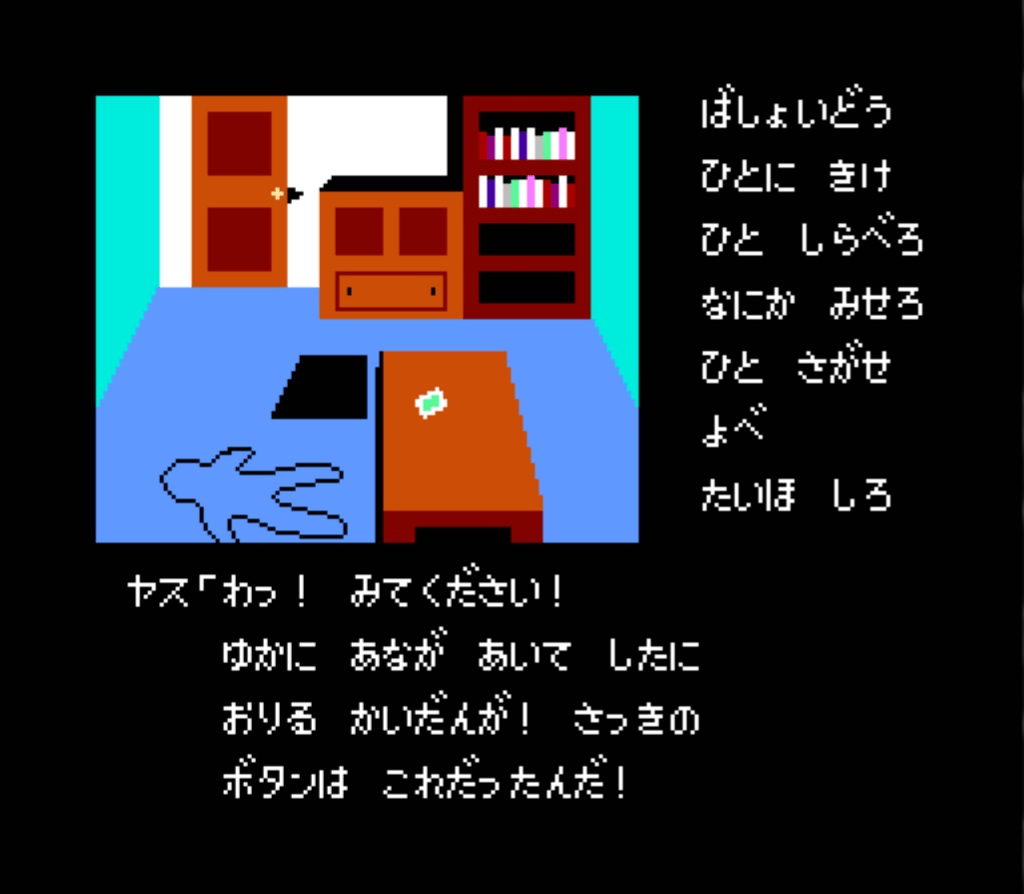

Horii then went on to make his mark with a suspenseful murder mystery game for PC, The Portopia Serial Murder Case. When it came time to port the game to the Famicom, Horii teamed up with Nakamura and immediately the two faced a critical challenge: trying to squeeze the full functionality of a keyboard into the famicom’s simple gamepad. Their solution was revolutionary: they replaced the PC’s text parser with a simple, elegant menu-based command system. Players could now “TALK,” “LOOK,” and “TAKE” using just a D-pad. They had, out of necessity, invented the very interface that would define the console RPG.

In October of 1983, Enix sent the two programmers to Applefest where they discovered the foundational American PC RPGs Wizardry and Ultima on an Apple II. Captivated by the sense of growth and adventure but knowing their brutal difficulty and complex keyboard commands were a non-starter for the Famicom’s massive, mainstream audience, their goal became clear. The two would use the simple, intuitive command system they’d built for Portopia to translate the feeling of a Western RPG into a language everyone in Japan could understand.

Assembling a Dream Team

A great quest requires legendary heroes, and Horii knew he couldn’t do it alone. His unique position as a writer for Shonen Jump gave him the ultimate advantage. His editor also happened to be the editor for a manga artist who was rapidly becoming a cultural icon: Akira Toriyama. By this time, Toriyama was a superstar. His comedy series Dr. Slump had sold over 35 million copies, and his new adventure series, Dragon Ball, was already a phenomenon. Toriyama’s distinctive art was a perfect blend of heroic fantasy and whimsical charm and gave the project immediate, massive brand recognition. Suddenly, this new game looked like the manga and anime every kid in Japan already loved.

The final piece of the trinity fell into place through sheer luck. Koichi Sugiyama, a veteran and highly respected composer for film and television, was also an avid gamer. He happened to send a feedback postcard he found in a different Enix game. When an employee saw the famous name, they reached out, and Sugiyama was brought on to compose the score. His classically trained background produced a grand, orchestral soundtrack that elevated the game far beyond the typical 8-bit chiptunes of the day. The dream team was assembled: Horii the storyteller, Toriyama the artist, and Sugiyama the composer.

The hype in Japan, fanned by extensive coverage in Shonen Jump, was immense. The release of Dragon Quest was a national event. The first game sold 1.5 million copies, the second 2.4 million. The launch of Dragon Quest III in 1988 was so anticipated that it caused thousands of kids and adults to skip school and work, leading to news reports of truancy and arrests. This was the colossus Nintendo of America thought it was bringing to the West.

From Hero to Zero

At its core, Dragon Quest was a brilliant fusion of familiar elements, distilled for a wider audience. Horii fused the tense, first-person battle perspective of Wizardry with the grand, top-down overworld exploration of Ultima. But where those games were punishing, Horii’s design was forgiving. If you died in Wizardry, your character could be gone forever. When you fell in battle in Dragon Quest, the King simply revived you at the castle, letting you keep all your precious experience points while only taking half your gold. This single choice transformed the experience, removing soul-crushing frustration and encouraging persistence.

The entire game was built on the elegant menu system perfected in Portopia, making it immediately playable with a simple controller. Horii saw the game as a manga you could play, using a clear narrative with a visible end-goal to act as rails guiding the player through the adventure.

But this carefully crafted, accessible masterpiece was not what arrived in our mailboxes. The journey to North America was a brutal act of cultural translation. First, a legal hurdle: the name Dragon Quest was already trademarked by TSR, the publisher of Dungeons & Dragons, for a tabletop RPG. Thus, Dragon Warrior was born, a name that immediately set a more aggressive, action-oriented tone.

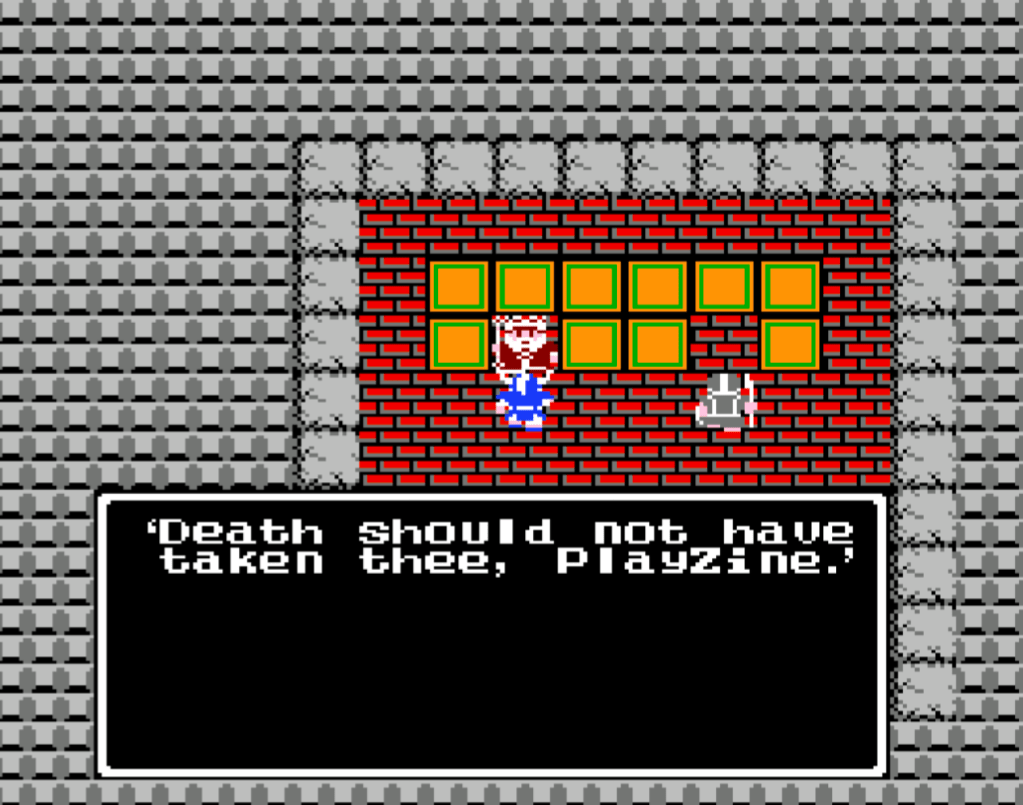

The localization team at Nintendo then made a bizarre and fateful decision. They threw out Horii’s contemporary, often humorous Japanese script and rewrote the entire game in a stuffy, pseudo-Elizabethan English full of “thees” and “thous”. The goal was to align the game with the Western high-fantasy tradition of Tolkien, a language they thought American kids would understand better than Toriyama’s whimsical manga adventures Yuji was drawing inspiration from. The game that arrived was watered down for western audiences with a more serious tone.

The Million Cartridge Gambit

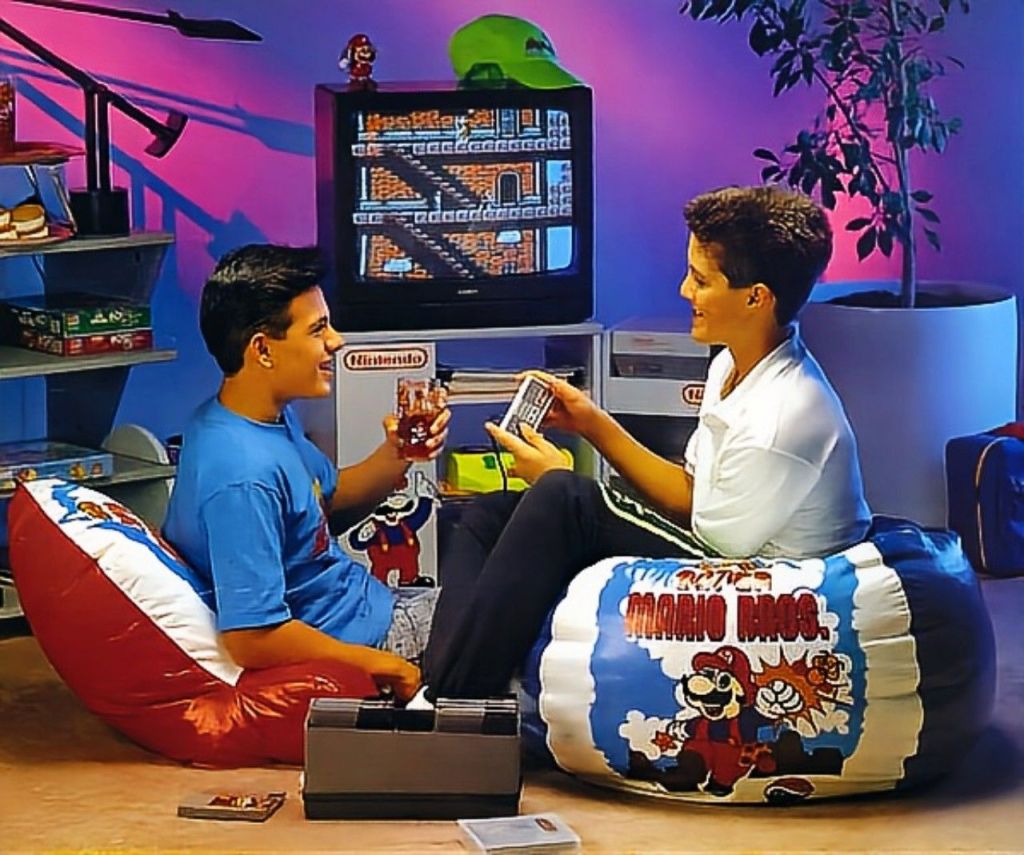

In 1989, the North American console market was a hostile environment for a slow-paced, text-heavy game. We were a nation of action gamers, our thumbs conditioned by the reflex-based twitch of Sega’s Arcade Thrills and Nintendo’s precision point platforming. An RPG was something you played on a bulky PC in the den, not on the living room TV. The marketing only made things worse. The epic box art created an expectation for a gritty action game, a promise the simple, sprite-based reality could never fulfill. The result was a commercial disaster. Initial sales were dismal, and Nintendo was left with a financial liability in the form of a million unsold cartridges.

What happened next was an act of pure desperation. To solve their massive inventory problem, Nintendo launched one of the most consequential promotions in gaming history. In 1990, they offered a free copy of Dragon Warrior to every new Nintendo Power subscriber. For the low price of $15, a $40 game showed up at your door. But this was more than just a fire sale to clear dead stock, it was also a calculated, if reluctant, investment in the future.

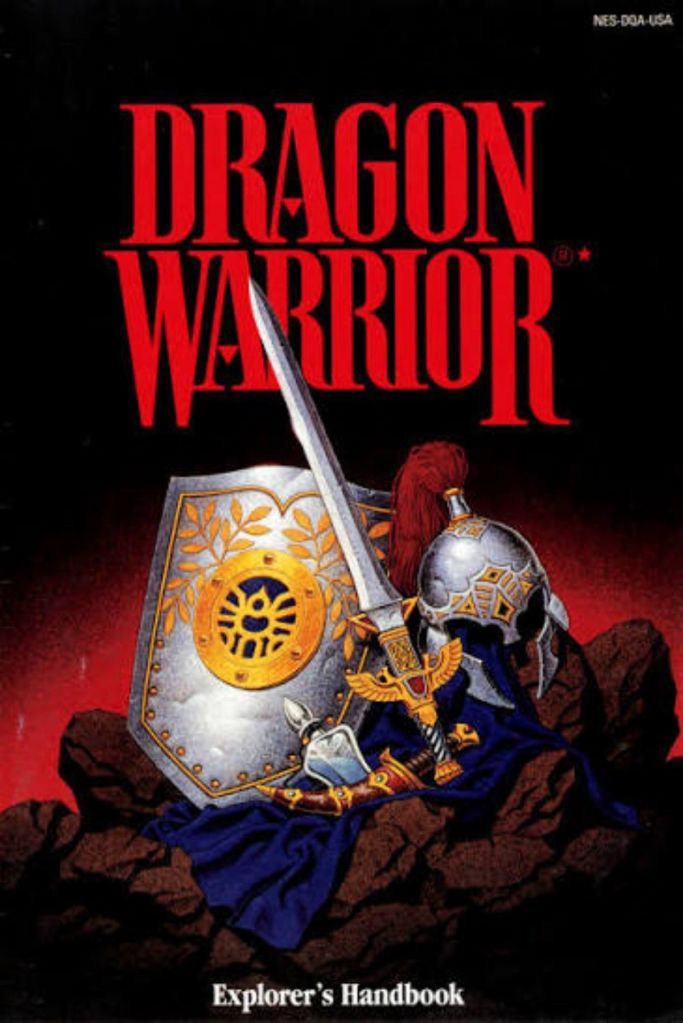

Crucially, the package included not just the game, but a 64-page, full-color Explorer’s Handbook. This guide was a tacit admission by Nintendo that its audience had no idea how to play this game. It provided maps, a bestiary, and a walkthrough, effectively holding our hands and teaching us the new vocabulary of grinding, of talking to every NPC and of saving up gold for a better sword.

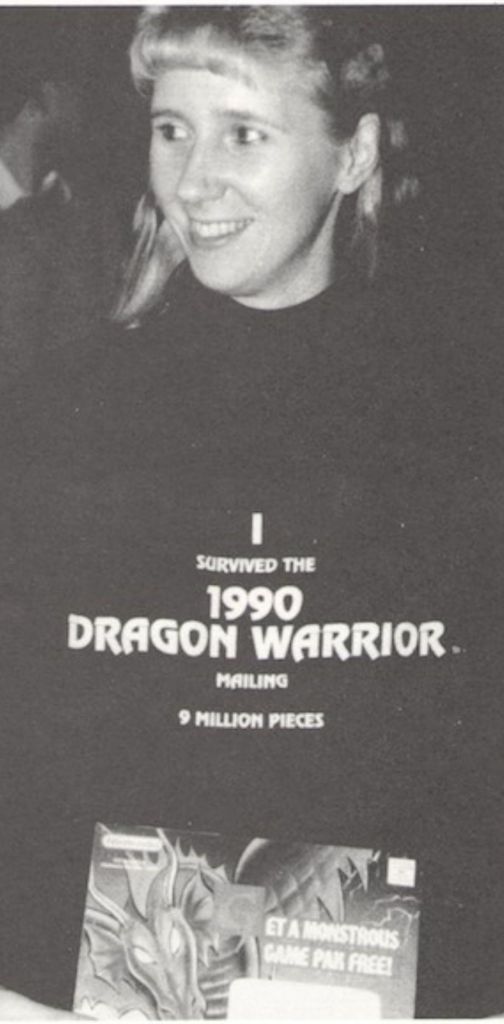

The giveaway was a logistical nightmare, Nintendo employees who survived the ordeal of mailing over a million cartridges reportedly got commemorative T-shirts, but it was also a smashing success for the magazine.

For the Dragon Warrior brand, however, the damage was done. By making the game free, Nintendo had unintentionally positioned it as a budget title, a perception that would haunt the series in the West for years. It allowed its chief rival, Final Fantasy, which arrived in 1990 as a full-priced retail game, to quickly overtake it as the premiere JRPG brand in North America.

Gateway to a Genre

The legacy of Dragon Warrior in North America is a beautiful paradox. The strategy designed to salvage the brand’s failure ended up devaluing it, ceding a generation of dominance to its rival. Yet, its true success wasn’t in sales figures, but in its role as an accidental, brute-force educational program. The giveaway put the foundational text of the JRPG genre into a million homes and, with its bundled handbook, taught an entire generation of players how to read it.

The players who patiently grinded Slimes outside Tantegel Castle were the same ones who were perfectly prepared for the more complex stories and systems of Final Fantasy. Dragon Warrior was a commercial failure and a cultural triumph, the free game that cost us nothing and brought the RPG full circle from the PC to the NES via the JRPG.

Mag Coverage

Nintendo Power #7, Jul/Aug 1989

Nintendo Power #8, Sep/Oct 1989

Leave a comment