Japan’s Secret Champion

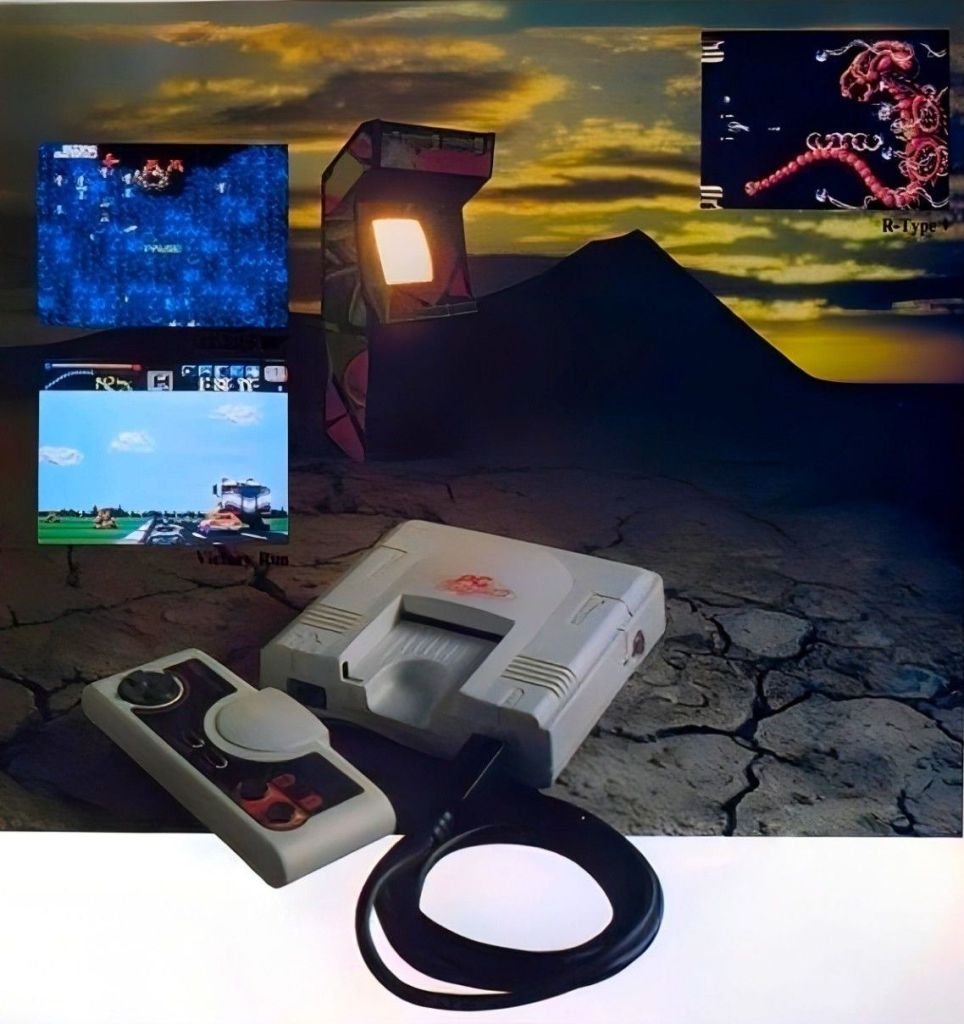

It was an enigma, a black plastic phantom lurking in the electronics aisle of Sears or Toys “R” Us. You’d wander past the shelves with your favorite transformers and T.M.N.T action figures, beyond the buzzing wall of CRT televisions and Nintendo products and there it would be tucked in the back. It sat on a hidden shelf, bulky and imposing, a stark contrast to the friendly grey box of the NES we all knew and loved. The name itself was a mouthful of pure 90s attitude, TurboGrafx-16, a promise of speed, power, and something fundamentally more. And the games, they weren’t the chunky plastic cartridges we’d blow on for good luck. They were tiny, impossibly thin, credit-card sized things called HuCards, futuristic and utterly strange.

You might have seen it running Keith Courage in Alpha Zones, a completely forgettable pack-in title with a generic hero and bland gameplay that did absolutely nothing to sell the “turbo” power promised on the box. It was a machine that felt both incredibly advanced and completely out of touch, a whisper on the playground that everyone heard of but nobody owned.

It was expensive, the marketing was confusing, and its mascot was a caveman with a giant head. For most of us in North America, the TurboGrafx-16 was a curiosity, a console that existed on the periphery of our vision while we were laser-focused on the escalating war between Nintendo and Sega. But across the ocean, this misunderstood machine had a secret identity. In Japan, where it was known as the PC Engine, it was a champion, a giant-slayer, and for a glorious time, the undisputed king of the next generation.

Looking Beyond the NES

To truly understand the TurboGrafx-16, you have to rewind the tape to the late 1980s, a time when the video game world was an empire of one. The NES had single-handedly resurrected the industry from the ashes of the great video game crash of 1983. Its dominance was absolute, holding nearly 95% of the market share. But after four years on top, the 8-bit hardware was starting to show its age. Games were frequently plagued by sprite flicker and frustrating slowdown when the action got too intense. Gamers, especially the hardcore arcade crowd, were hungry for something more, something faster, something that looked and felt like the future.

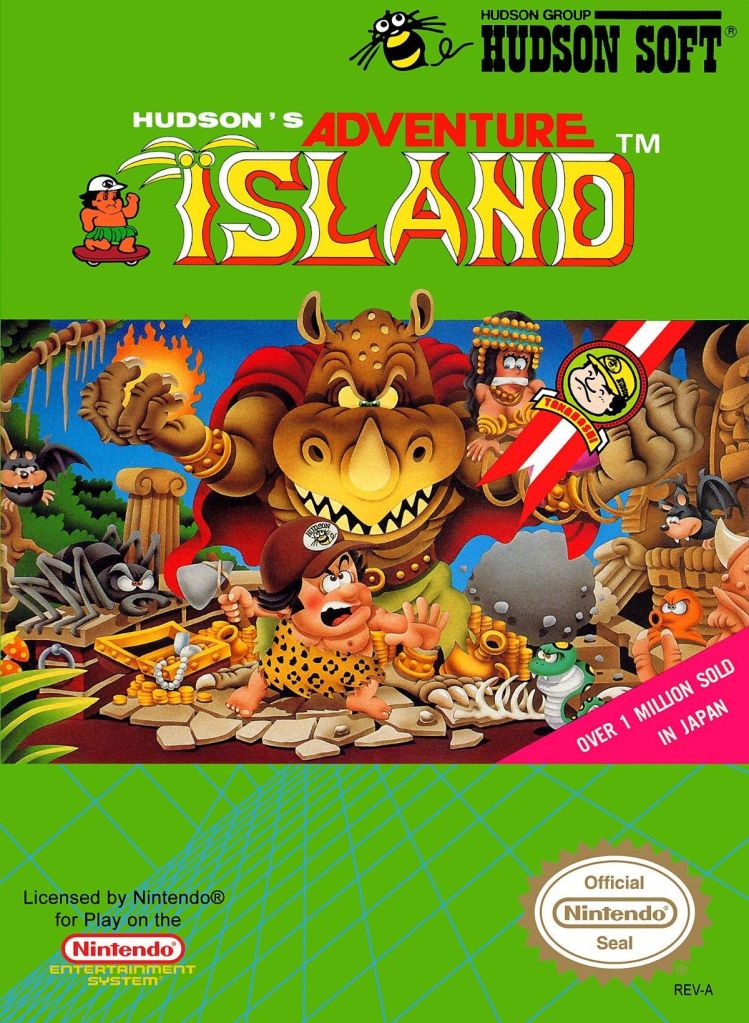

It was into this perfect window of opportunity that Hudson, the very first third-party developer for Nintendo, had become a master of the Famicom, creating immortal hits like Bomberman and the Adventure Island series. They knew the NES hardware inside and out and they were acutely aware of its limitations. This mastery and intimate knowledge of the existing technology naturally led them to envision what could come next: a new hardware collaboration with advanced graphics chips that could overcome the 8-bit system’s shortcomings.

Emboldened by their success and their deep technical skill, they designed their own advanced graphics chips that could push pixels like nothing else. They offered their creation to Nintendo, proposing a new hardware collaboration, but Nintendo, comfortable in its market dominance, passed on the offer.

Perfect Strangers

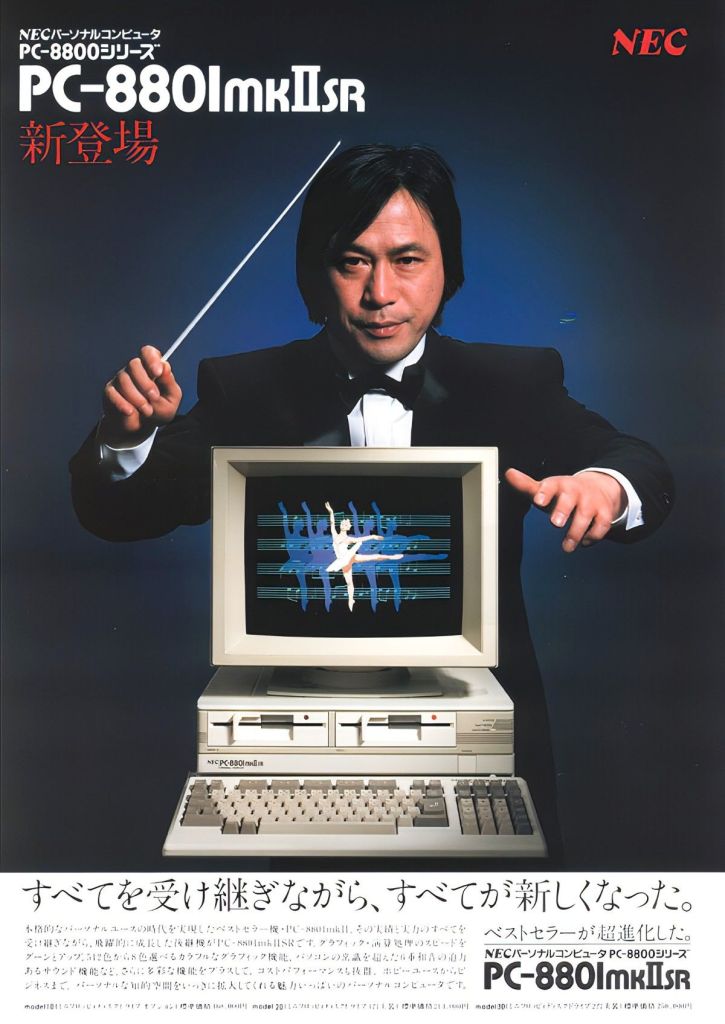

Undeterred, Hudson found their perfect match in NEC, a Japanese electronics titan that dominated the PC market with its PC-88 and PC-98 computer lines but had absolutely no experience in the console space.

It was a match made in heaven. Hudson brought the gaming genius and the revolutionary chip designs, NEC brought the manufacturing muscle and the distribution network, and together they created the PC Engine. The machine they built was a marvel of focused and elegant engineering. The PC Engine launched in Japan on October 30, 1987, a full year before Sega’s Mega Drive and a staggering three years before the Super Famicom would arrive to challenge it.

At its heart was a technical choice that would spark debate for years. It ran on an 8-bit CPU, a supercharged version of the same 6502 chip family found in the NES, but it was paired with a powerful, dedicated 16-bit graphics subsystem. This hybrid design was a stroke of genius. It kept manufacturing costs down while allowing the console to produce visuals that were lightyears ahead of the competition. The PC Engine could splash up to 482 colors on screen at once, a jaw-dropping number compared to the NES’s paltry 25 or even the later Sega Genesis’s 61. This made it an absolute powerhouse for the 2D, sprite-heavy shooters and action games that ruled the Japanese arcades.

The port of Irem’s legendary shooter R-Type was a technical masterpiece, a near-perfect arcade conversion that proved the little white box could bring the coin-op experience home with stunning fidelity. It became the definitive console for an entire genre, a sacred haven for hardcore shooter fans.

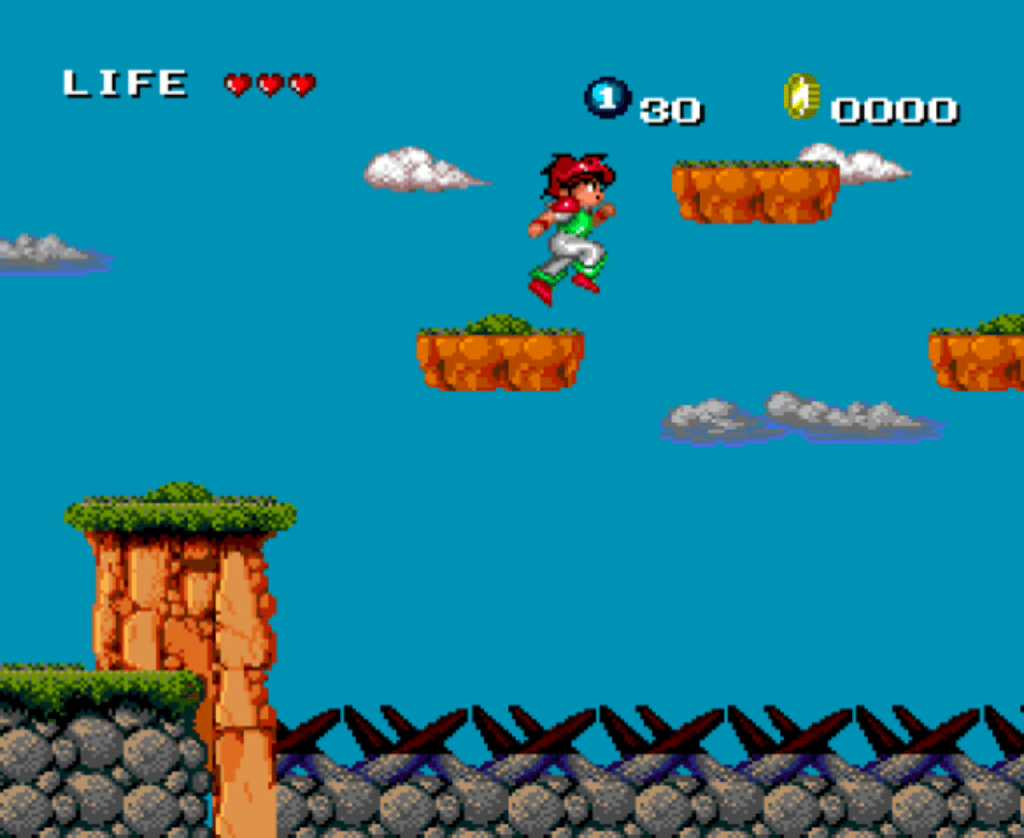

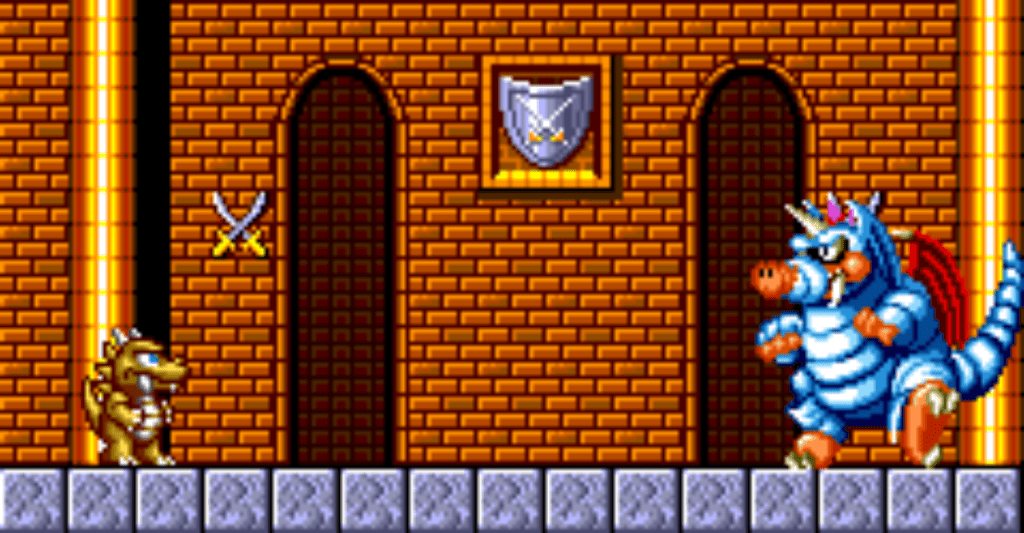

But it wasn’t just a one-trick pony. The system was also home to some of the era’s best platformers, like Hudson’s masterful port of Wonder Boy III: The Dragon’s Trap (known as Dragon’s Curse on the TurboGrafx-16). This was a sprawling action-adventure with gorgeous, vibrant art and a shapeshifting mechanic that allowed you to transform into different creatures, each with unique abilities needed to traverse its massive, interconnected world. It still feels brilliant today.

The console’s success in Japan was meteoric. It sold half a million units in its first week and by 1988 was consistently outselling the mighty Famicom, shattering Nintendo’s monopoly and proving that a new generation of gaming had truly begun. The PC Engine crushed the Sega Mega Drive, selling over two million more units and cementing itself as the true number two console of the generation.

A Console First: The CD-ROM Lands in Japan

The TurboGrafx-16’s greatest innovation arrived in December 1988 when NEC released the CD-ROM² add-on. This made the PC Engine the first console in history to use CDs for its games, a move that would change everything.

The massive storage capacity of a CD, around 650MB compared to the tiny size of a HuCard, allowed for things never before possible on a home console. Developers could now include full Red Book audio soundtracks, replacing the charming but repetitive chiptunes of the past with rich, orchestrated scores and rock anthems. They could add extensive voice acting and, most impressively, stunning, feature-length anime cutscenes.

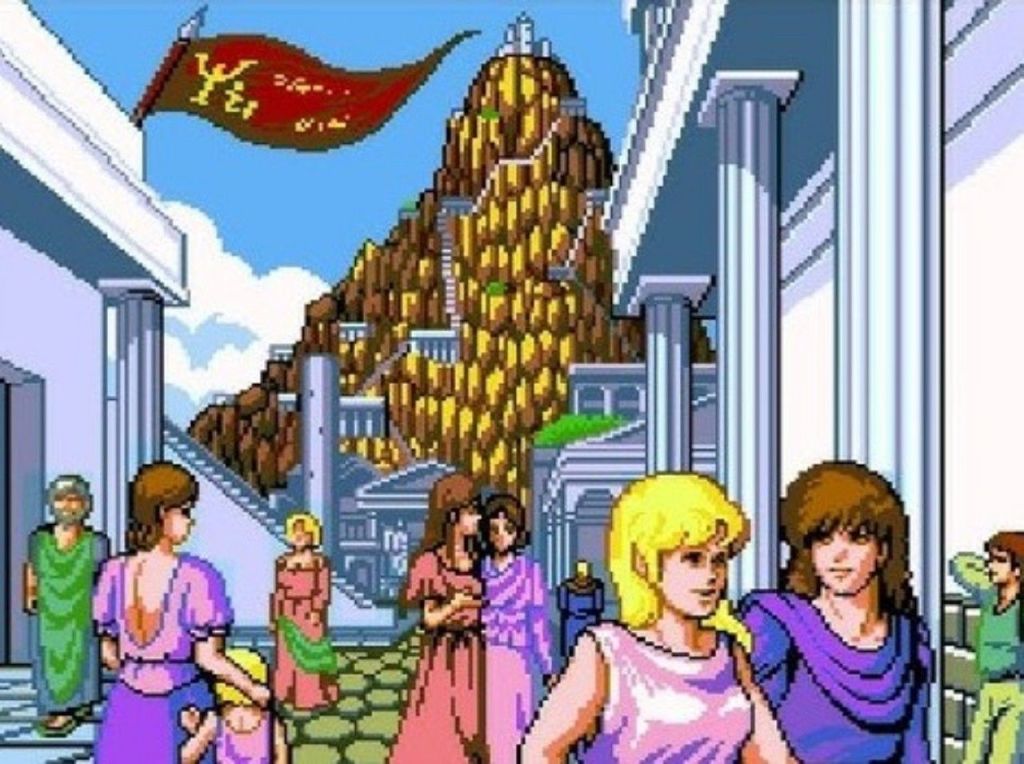

This new format gave birth to legendary titles that defined a new era of cinematic gaming. The action-RPG series Ys, particularly the combined release of Ys Book I & II, became a cinematic epic. Its sweeping story was now told through animated sequences and voiceovers, its world brought to life by a soaring, unforgettable soundtrack. It set a new standard for storytelling in the genre.

The CD format turned shooters into multimedia spectacles. The incredible Gate of Thunder used the disc to deliver a pulse-pounding, hard-rocking soundtrack that turned the intense on-screen action into a full-blown rock opera. And then there was Konami’s Castlevania: Rondo of Blood, a masterpiece of 2D action that many consider the absolute pinnacle of the entire series. Released exclusively on the PC Engine CD in Japan, it was a showcase for everything the format could do. Its gorgeous, fluid animation, branching level paths, and unforgettable CD soundtrack created an atmospheric, gothic horror experience that was simply impossible on any cartridge-based system of the time. It was the system’s ultimate killer app, the game that made the CD add-on a truly essential purchase.

Lost in Translation

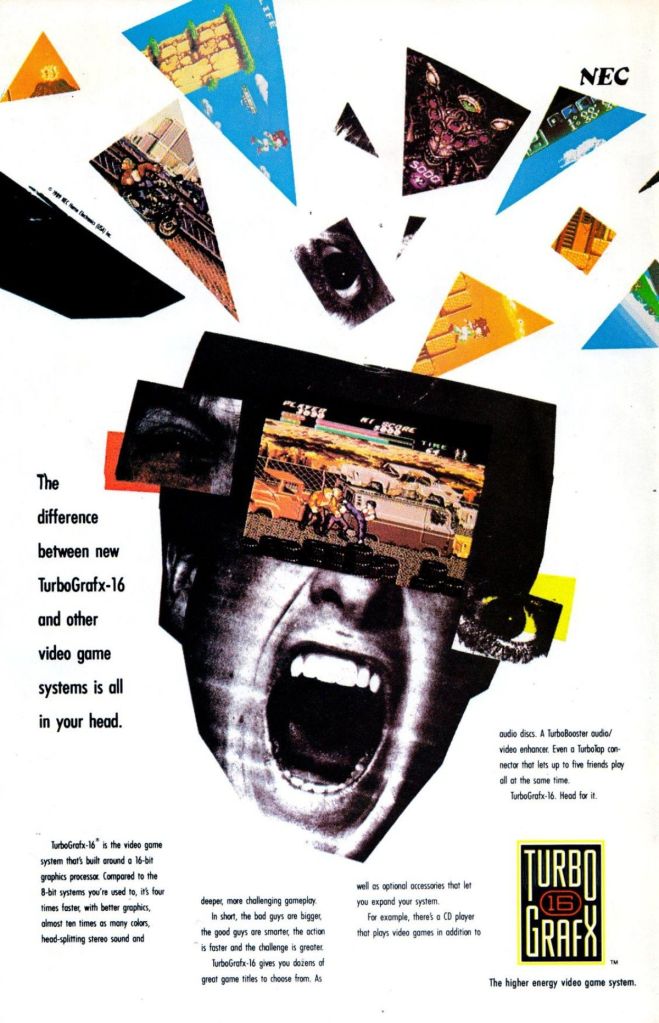

But this incredible Japanese success story makes its North American failure all the more baffling. The machine, rebranded as the TurboGrafx-16, didn’t arrive in North America until August 1989. This fatal two-year delay erased its crucial head start. Instead of launching into a world dominated by the 8-bit NES, it went head-to-head with the brand new, more powerful, and brilliantly marketed Sega Genesis.

From the very beginning, NEC’s American division made a series of disastrous strategic choices. They scrapped the PC Engine’s sleek, compact, and frankly beautiful white design for a bulky, generic black box, fearing the original was too small and toy-like for US consumers. The “16” in the name was technically true for the graphics processor but deeply misleading for the 8-bit CPU, giving Sega an easy and effective marketing win with its 16-bit Genesis.

The blunders piled up. The terrible pack-in game, Keith Courage, was an immediate turn-off. The console inexplicably launched with only a single controller port, requiring a pricey TurboTap accessory for multiplayer gaming, a baffling decision when even the old NES came with two. The marketing campaign was out of touch and failed to build any real hype or brand recognition.

The very things that made the PC Engine a success in Japan, its focused library of amazing shooters and its deep well of Japanese-centric RPGs, were lost in translation and failed to connect with a mainstream American audience that Sega was successfully courting with sports titles and arcade hits.

Gaming’s Greatest What-If

To own a TurboGrafx-16 in North America was to be part of a secret club. You knew you had something special, a machine that felt like a direct line to the heart of the Japanese arcade scene. You were playing the definitive versions of classics, experiencing the birth of CD gaming years before anyone else, and enjoying a library of quirky, colorful, and unapologetically hardcore games that your Nintendo-loving friends had never even heard of.

The console remains one of gaming’s most fascinating what-if stories. It’s a testament to brilliant, focused design and a timeless cautionary tale about the critical importance of marketing, timing, and understanding your audience. For those of us who found it in that department store aisle, it was a gateway to a different world of gaming, a technological marvel that may have lost the war in America but stands as a testament to innovation and a beloved, if niche, chapter in gaming history.

Leave a comment