The Blue Bomber

That opening screen is burned into our collective memory. As a slow melodic track begins, the story fades in, setting the stage in the year 200X. We learn of the super robot named Mega Man, a creation of Dr. Light built to stop the evil desires of Dr. Wily. But peace was short-lived. The text reveals that after his initial defeat, Dr. Wily has returned, creating eight of his own robots to counter Mega Man.

Just as this new threat is established, the screen changes. The camera begins its steady, relentless climb up a skyscraper, revealing the purple hues of a futuristic metropolis stretching into the distance. The ascent finally rests on that solitary figure, his blue silhouette stark against the night. It’s Mega Man, his hair flowing in the wind, a lone hero now faced with an even greater challenge.

Then, that high energy 8-bit banger kicks in, a driving, heroic melody that promised pure adrenaline. This was Mega Man 2. It wasn’t just another cartridge you plugged into your NES. It felt like an event, a bolt of blue lightning that redefined what a video game could be. But the true story of the Blue Bomber’s greatest adventure begins not with a bang, but with the ghosts of past failure.

An Anime Passion Project

To understand why this title screen felt like a revolution, you have to remember the baffling, almost nightmarish image that came before it. You have to go back to the video rental store, the air thick with the smell of plastic VHS cases. Your eyes scan the rows of Nintendo games, past the familiar faces of plumbers and princesses, and then you see it. The cover of the first Mega Man. A strange, middle-aged man in a baggy yellow and blue suit, holding a pistol, stands awkwardly against a backdrop of palm trees. Artwork that was reportedly created in just six hours by an artist who had never even seen the game.

That bizarre cover was the first sign of a profound misunderstanding. In 1987, Capcom was the king of the arcade, but Mega Man, or Rockman as he was known in Japan, was a gamble. It was a game built from the ground up for the home console by a tiny, passionate team of just six people. The game’s director, Akira Kitamura, dreamed up the core idea of a hero who could absorb the powers of his enemies. A junior artist named Keiji Inafune was tasked with refining Kitamura’s pixel art into the polished, anime-style illustrations for promotion.

Their inspiration was clear. The game’s DNA owes a massive debt to Osamu Tezuka’s classic anime, Astro Boy. The heroic boy robot, the benevolent scientist creator, and the jealous rival all echo the classic anime’s narrative. This little blue robot wasn’t just another game, it was a way for kids to live the story that Astro Boy only let them watch. Megaman’s deep resonance with the quintessential anime power fantasy led to its immense popularity, shaping the future of gaming from that point onwards.

But in North America, that future was dead on arrival. The game was an absolute commercial flop. The now-legendary bad box art was the first wound and for the few who braved the awful cover, the game itself was a monument to “Nintendo Hard” design. It had no password system and a Game Over sent you right back to the stage select screen to start the level all over again. There were no E-Tanks to refill your health, and the Yellow Devil made it nearly impossible to reach the ending. This difficult structure, combined with weak marketing from a still-nascent Capcom USA, doomed the game to the bargain bin. The franchise was a failure in North America.

The After-Hours Rebellion

By all rights, the story should have ended there. Capcom’s management saw the dismal sales figures and decided to shelve the series. But the story of Mega Man 2 is not a story of corporate strategy, it is the story of a clandestine operation. The game was willed into existence through the sheer defiant passion of its creators. Convinced of the game’s potential, director Akira Kitamura bypassed his own superiors and appealed directly to Capcom’s vice president for one more shot. He was granted reluctant approval under one critical condition: the project could not interfere with the team’s official duties.

And so, Mega Man 2 became an after-hours rebellion. In a stunningly brief window of nearly four months, a small, dedicated team built a masterpiece in their spare time. They worked nights and weekends, fueled by a belief that they were correcting every single flaw of the first game. This corporate indifference became their greatest weapon. With no executive oversight, the team was blessed with total creative freedom. They weren’t trying to meet a sales projection, they were trying to perfect their vision.

Domo Arigato, Mr. Roboto

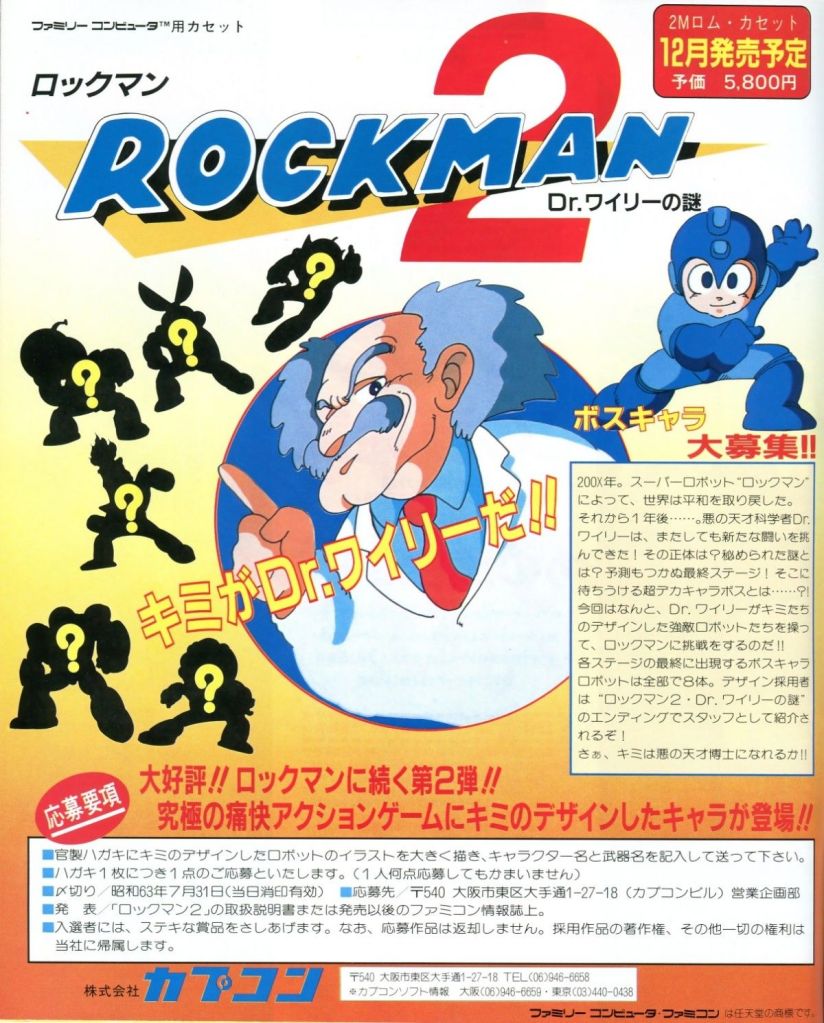

This newfound freedom led to an explosion of creativity, and nowhere was this more apparent than in the game’s iconic lineup of villains. The roster was expanded from six to eight Robot Masters, and their creation was a pioneering act of community engagement. The team solicited boss designs directly from fans in Japan, receiving over 8,000 submissions. This masterstroke forged an immediate bond between the developers and their audience. Keiji Inafune took on the role of refining these raw, imaginative fan drawings, polishing them into the legendary pixel art sprites that would become household names.

More importantly, the team perfected the rock-paper-scissors formula that the first game had introduced. Mega Man 2 was an elegant puzzle box of weaknesses and strengths. Defeating the perpetually grinding Metal Man granted you the Metal Blade, a ridiculously overpowered weapon that could be fired in eight directions and shredded through Wood Man’s leafy defenses. Conquering Wood Man in his forest fortress yielded the Leaf Shield, the perfect counter to the relentless tornadoes spewed by Air Man.

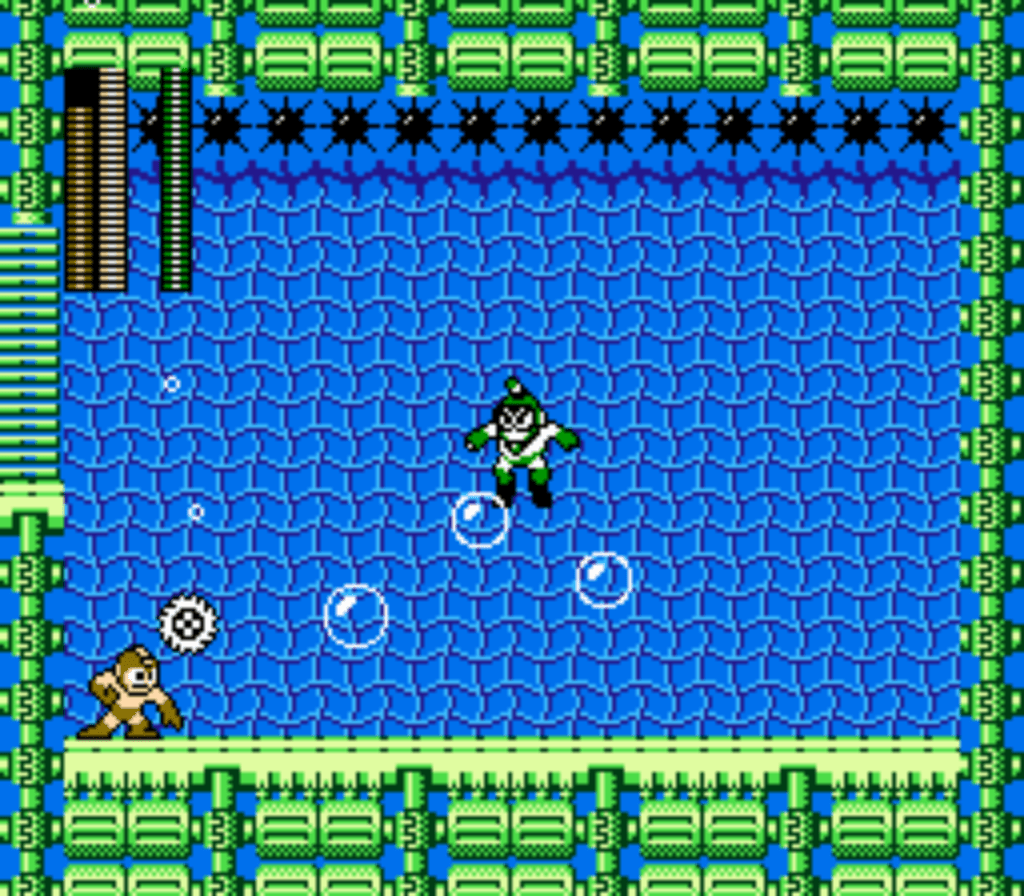

Cracking this sequence, discovering the ideal path through the eight masters, was a revelation. It transformed the game from a simple action platformer into a strategic quest for knowledge, a core part of the shared experience passed around in whispers on the schoolyard. From the anxiety-inducing laser corridors of Quick Man’s stage to the charming, gurgling depths of Bubble Man’s underwater lair, each master presented a distinct and unforgettable challenge.

And then there was the music. The soundtrack for Mega Man 2, composed primarily by Takashi Tateishi, is not just one of the greatest of the 8-bit era, it is one of the greatest video game soundtracks of all time. Tateishi wrestled with the NES’s primitive sound chip, meticulously programming every note to craft driving, complex melodies that pushed the hardware to its absolute limit.

From the electrifying synth of Metal Man’s stage to the aquatic grooves of Bubble Man’s theme, and the frantic pace of Quick Man’s music, each boss stage had a memorable tune. And who can forget the iconic, pulse-pounding theme for the first Dr. Wily stage, calling back to the intro screen and hyping up the player for the final confrontation. In a time before the internet, this music was the game’s secret weapon. The tunes were so incredibly catchy they became playground anthems, hummed by kids across the country.

Storming the Skull Fortress

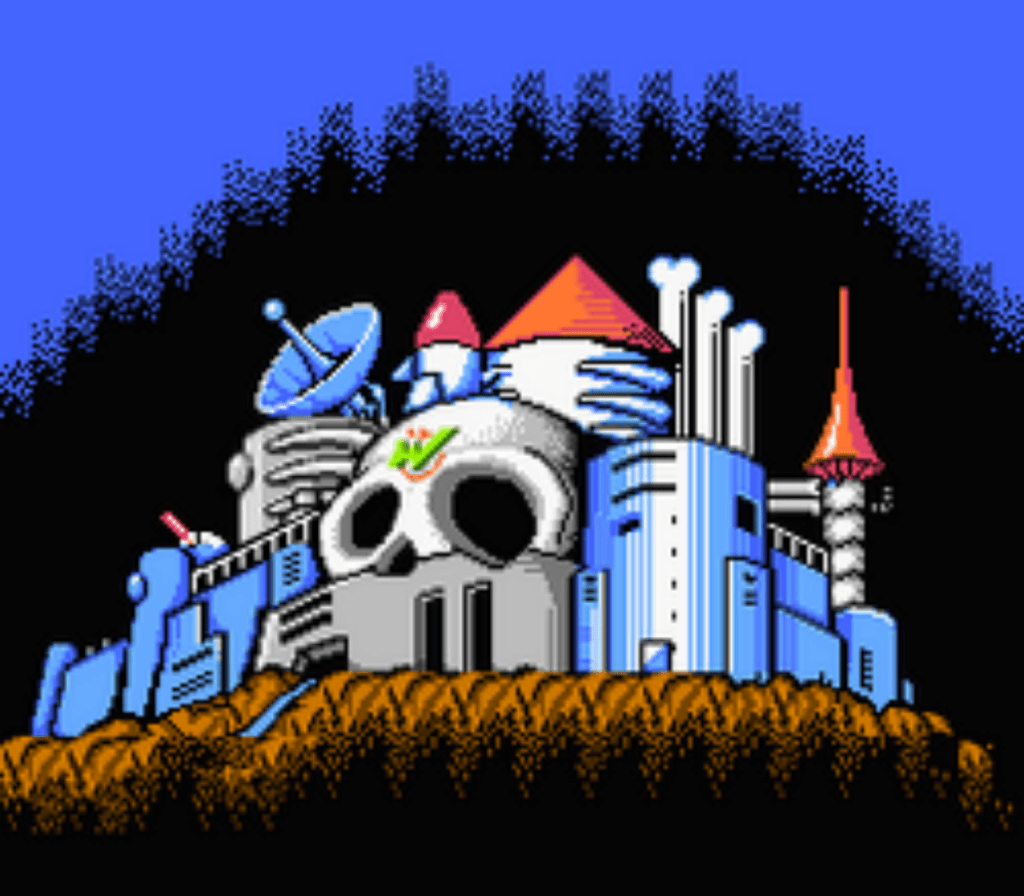

After defeating the eight Robot Masters, the game underwent a dramatic tonal shift as Dr. Wily’s Skull Fortress appeared on the map. This was it. The final act. The levels were no longer themed to a single personality, they were brutal, mechanical deathtraps designed for one purpose: to crush you.

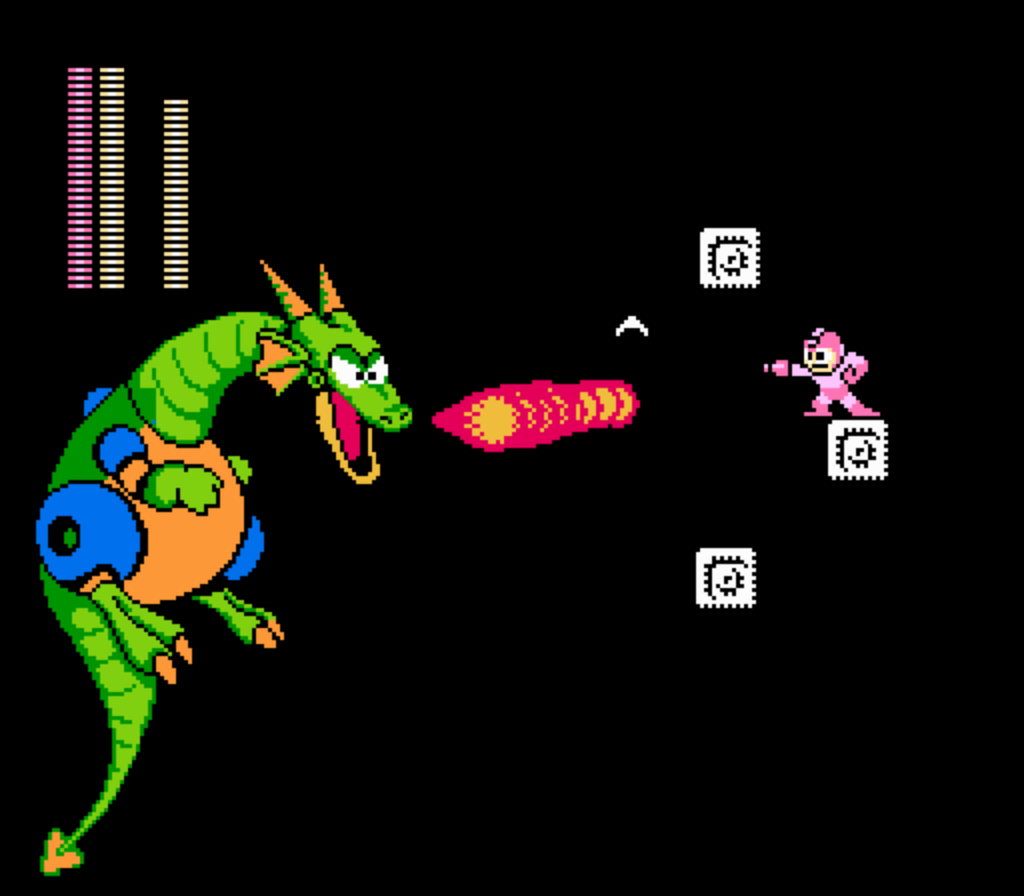

The culmination of the initial assault is a moment burned into the memory of every player: the Mecha Dragon. After you climbed a ladder into the sky and deftly traversed a set of small disappearing blocks, a colossal, screen-filling dragon emerged from the darkness. It was a true spectacle on the NES, a moment of pure 8-bit awe and terror. Its fiery breath could kill you in seconds, and your only path to victory is by traversing a series of tiny blocks suspended over a bottomless pit. It was a legendary difficulty spike, a test of everything you had learned, and conquering it was a massive payoff that signaled you were truly ready to face Wily himself.

A Blueprint for a Dynasty

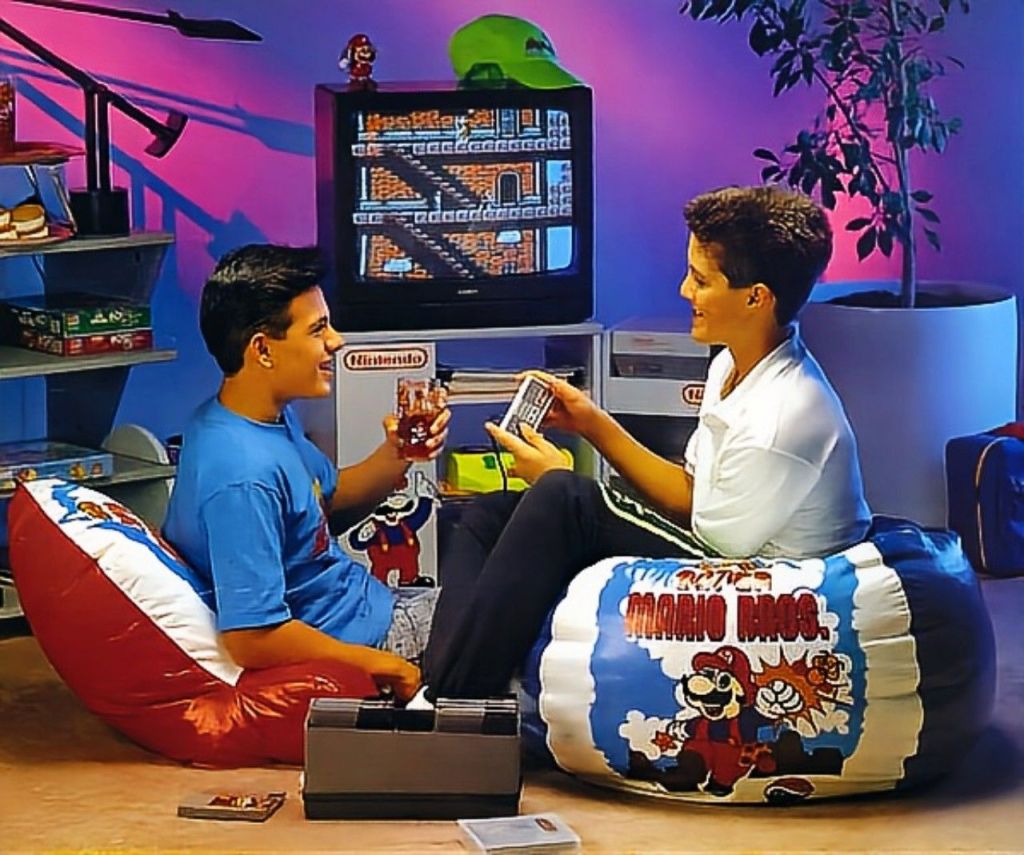

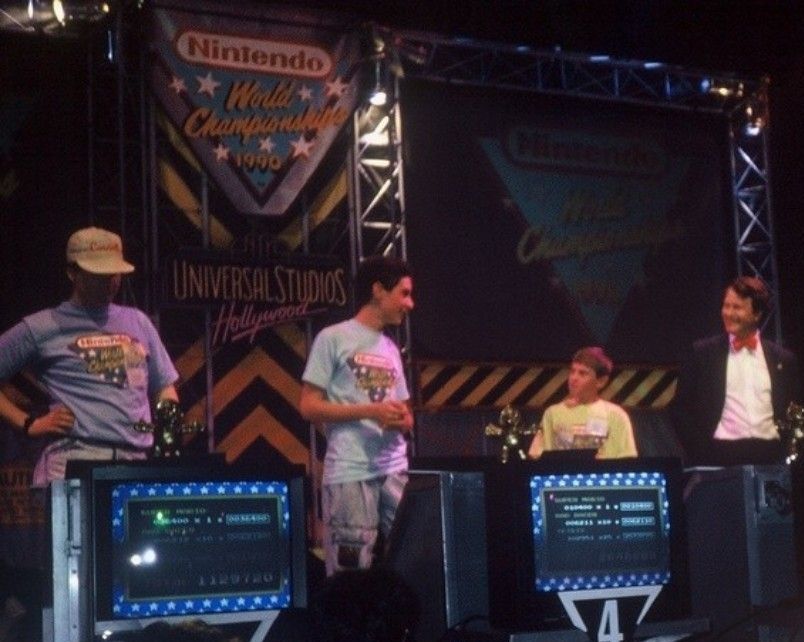

When Mega Man 2 finally hit North American store shelves in 1989, it was perfectly positioned for victory. A global semiconductor shortage had crippled Nintendo’s ability to manufacture its own cartridges, leaving a vacuum on store shelves. Kids with NES consoles were starved for a top-tier game, and Nintendo couldn’t provide one. Capcom’s secret masterpiece was there to answer the call.

The game’s success was supercharged by an unprecedented marketing push from an unlikely source. The July/August 1989 issue of Nintendo Power magazine gave the game the cover story, a massive 16-page spread usually reserved for Nintendo’s own titles. With their own blockbusters sidelined by the chip famine, Nintendo needed a third-party hero, and Capcom’s polished, passionate, and endlessly replayable adventure was the perfect fit.

This massive exposure helped Mega Man 2 sell over 1.5 million copies, making it the best-selling game in the series and proving to Capcom that their secret, after-hours project was a certified superstar.

I, Robot

The legacy of Mega Man 2 is a masterpiece of action platforming design. It did not just save a failed IP, it single-handedly established the Blue Bomber as a Nintendo icon. More importantly, it codified the very formula that would define an era of gaming. The structure of eight Robot Masters, the life-saving E-Tanks, the special mobility items, the password system, and the climactic boss rush in Dr. Wily’s castle all became the definitive blueprint for the classic series.

It was the perfect fusion of action, platforming, and strategy, an elegant design that felt both timeless and new. To play it today is to witness a pivotal moment in gaming history, the sound of a small group of creators, working on borrowed time, pouring all of their passion into a second chance. They didn’t just build a sequel. They built the legendary foundation upon which one of gaming’s most enduring icons would stand for generations to come.

Leave a comment