Sega Rises from the Grave

It was the sound that hit you first. A low, synthesized growl, a gravelly digital voice that clawed its way out of your television’s speakers and commanded you to “Rise from your grave!” For any kid lucky enough to get a Genesis on launch, it was the moment they realized the arcade had slammed into their living room. That voice, that single, crunchy audio sample, wasn’t just a sound effect, it was the sound of Sega tearing itself from the forgotten grave of the Sega Master System. It was a declaration of rebirth, the awakening of a sleeping giant, and the first shots of the 16-bit console war that shattered the summer calm.

Before this thunderous arrival, gamers were living in a completely different world. It was an empire ruled by a benevolent dictator whose word was law and whose pixelated adventures defined the childhoods of an entire generation. Sega, once a hopeful challenger, had been relegated to the shadows, its previous attempts swiftly crushed. But beneath the surface of this seemingly unshakeable empire, the minds at Sega were drawing up new battle plans in an attempt to exploit Nintendo’s hidden weakness, the burgeoning teenage market.

Drawing up the Battle Plans

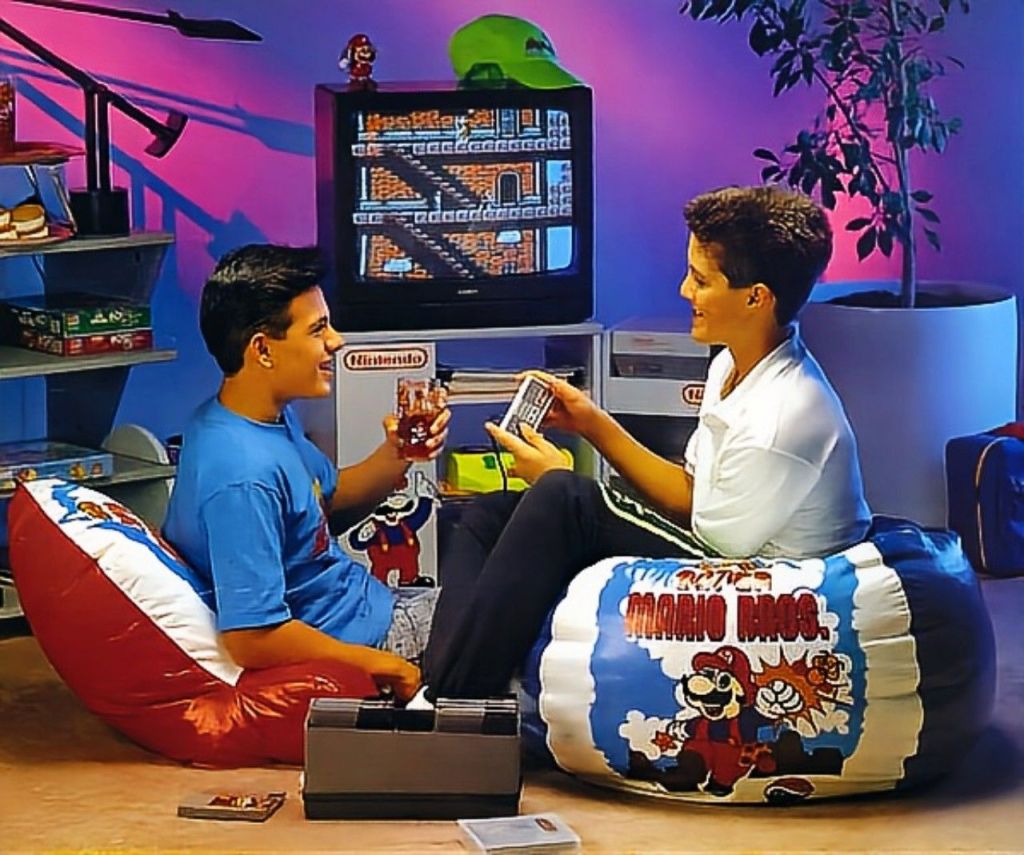

The living rooms of the late 1980s were owned by the NES. It wasn’t just a console, it was a cultural phenomenon and with nearly 95% of the home console market, the word Nintendo was synonymous with video games. Sega’s previous attempt to break this stranglehold, the Master System, was a dead system by this point, haunting the aisles of Toys “R” Us. Despite being technologically superior to the NES, it had been systematically suffocated in North America. Nintendo’s draconian third-party licensing agreements prevented developers from bringing their hit games to competing systems.

To take on this fight, Sega needed some heavy artillery and the Genesis was the weapon Sega forged for this war. Its design was a deliberate and stunning departure from the toy-like aesthetic of the NES. Inspired by high-end Japanese stereo equipment, the console was a sleek, jet-black machine with a prominent volume slider and a headphone jack for personal, immersive play. It looked serious. It looked cool. It looked like it belonged in the living room, not the playroom. The very name, Genesis, was a declaration of a new beginning.

Beneath that sophisticated hood was the heart of an arcade beast. The console was built around a powerful Motorola 68000 processor, the very same high-end CPU found in Sega’s arcade cabinets like Space Harrier and Golden Axe. This chip was the key as it gave developers the horsepower needed to create the fast, smooth-scrolling, sprite-heavy action that defined the arcade experience. Sega took a colossal gamble, ordering the expensive chips in such massive quantities that they secured them for a fraction of the market price, making this incredible power affordable for a home console.

When it came time to bring Sega’s 16-bit console to the North American market, the company was already fighting from its back foot as the console was struggling back home in Japan. It had launched a full year after a powerful competitor, NEC’s PC Engine, had already captured the hearts of hardcore gamers. Worse, the Mega Drive’s Japanese debut on October 29, 1988, was completely overshadowed by the release of Super Mario Bros. 3 just a week earlier, an event that consumed all the media attention and gamer cash. While Nintendo held the family market, NEC had expertly seized the enthusiast niche. The Mega Drive was doomed to a distant third-place finish in its own home. For Sega, North America wasn’t just another market, it was their only hope for survival.

Launching with a Hope and a Prayer

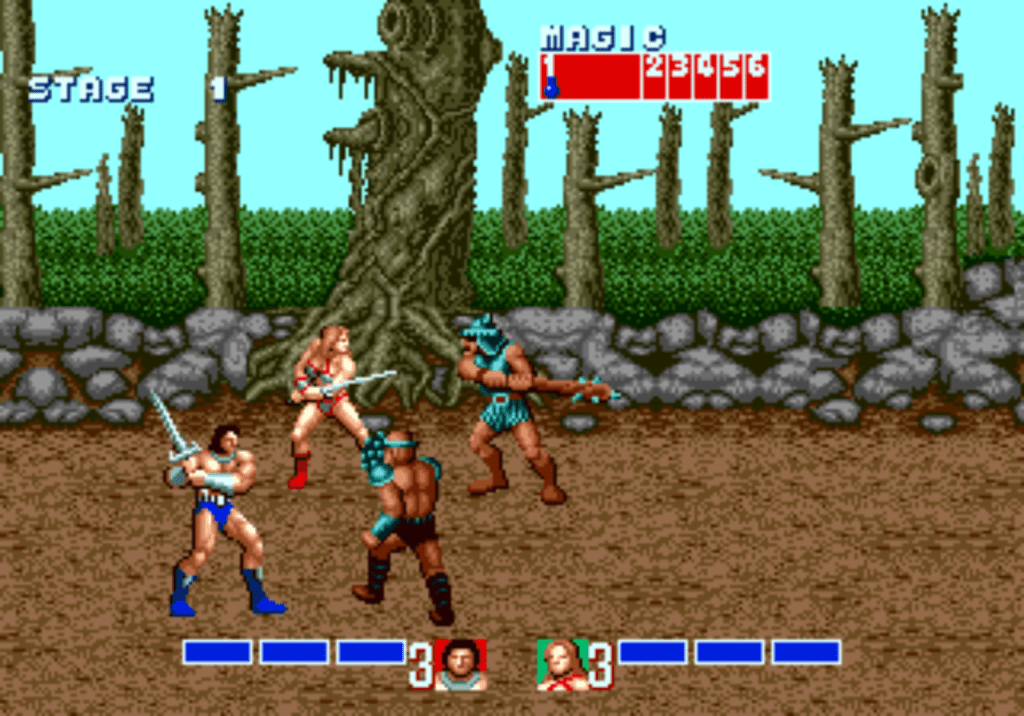

The Sega Genesis launched in North America on August 14, 1989, for $189. Altered Beast was the pack-in game and while its gameplay was considered shallow, its massive sprites and the iconic digitized voice made it an ideal title to introduce the powerful new system. It effectively showcased the Genesis’s ability to bring an arcade-like experience into the home, even if its long-term appeal was limited.

But Altered Beast was backed with some real depth from the strong variety of launch titles that arrived by its side. Alex Kidd in the Enchanted Castle was included to appeal to younger audiences and leverage the existing popularity of the Alex Kidd character, who had been Sega’s mascot up until this point. Last Battle, a beat-’em-up, offered a more mature and violent experience, targeting older players looking for something beyond Nintendo’s family-friendly offerings. Space Harrier II, a fast-paced rail shooter, showcased the Genesis’s ability to handle impressive scaling and sprite effects, appealing to arcade fans and demonstrating the console’s graphical power.

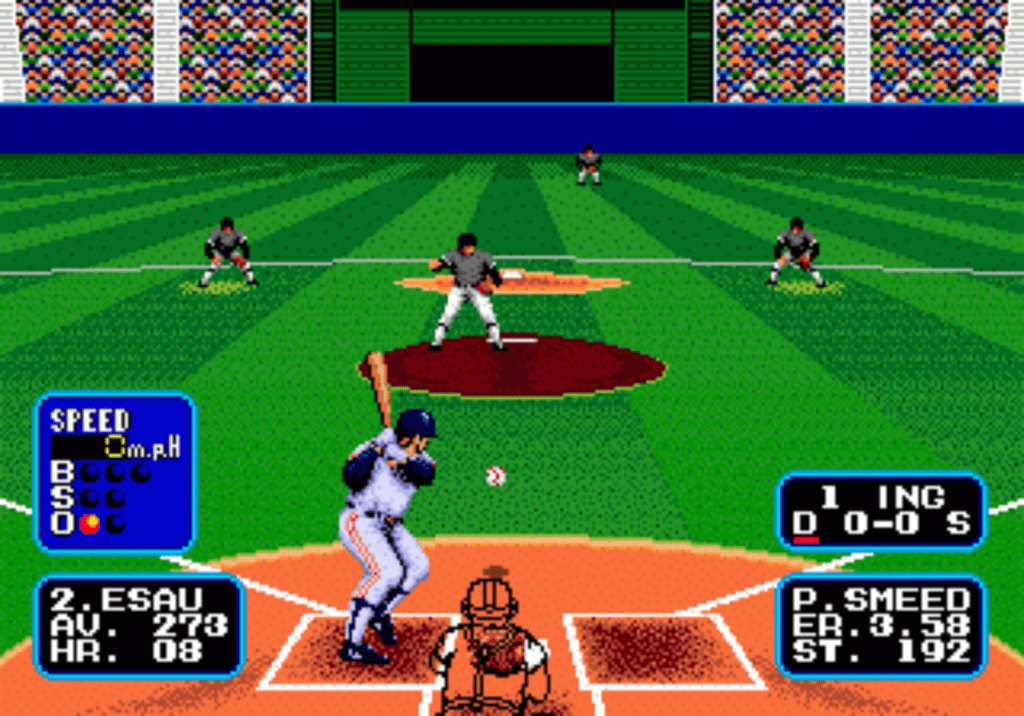

Rounding out the launch lineup was Thunder Force II, a technically impressive scrolling shooter, pushing the boundaries of what was possible on a home console, and Tommy Lasorda Baseball, a clear signal that Sega was targeting an older, sports-loving demographic that Nintendo had often overlooked, aiming to capture a wider market beyond traditional platformer fans.

Better Lucky than Good

Sega’s assault on North America could have been a complete disaster if it wasn’t for a few key openings left by their Japanese competitors. These competitors, despite their own strengths, inadvertently created opportunities that Sega was able to exploit. Without these crucial missteps or oversights from their rivals, Sega’s attempt to break into the North American market might have faced insurmountable challenges, leading to a very different outcome for the console war.

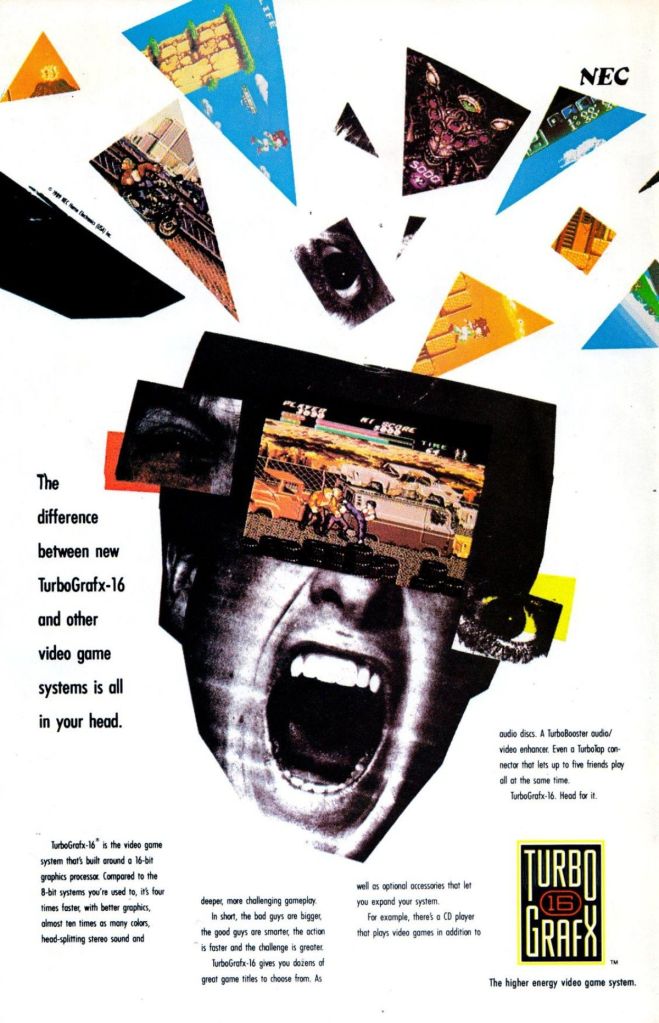

In Japan, the PC Engine was a beloved powerhouse that had masterfully captured the hardcore gaming crowd. But NEC fumbled the consoles journey across the Pacific. The TurboGrafx-16 stumbled into the American market with a complete lack of strategic awareness. Its marketing was confused and its design looked more like a curious peripheral than a next-generation titan.

The fatal blow, however, was the pack-in game. While Sega was preparing to blast living rooms with the arcade muscle of Altered Beast, the TurboGrafx-16 offered up Keith Courage in Alpha Zones. It was a painfully generic and utterly forgettable platformer that failed to showcase any of the console’s impressive graphical horsepower. It was a game that felt safe, a game that felt like it was trying to be a B-tier Nintendo title. The machine had the guts to be a loud but it arrived with a whisper, failing to give gamers a single compelling reason to care.

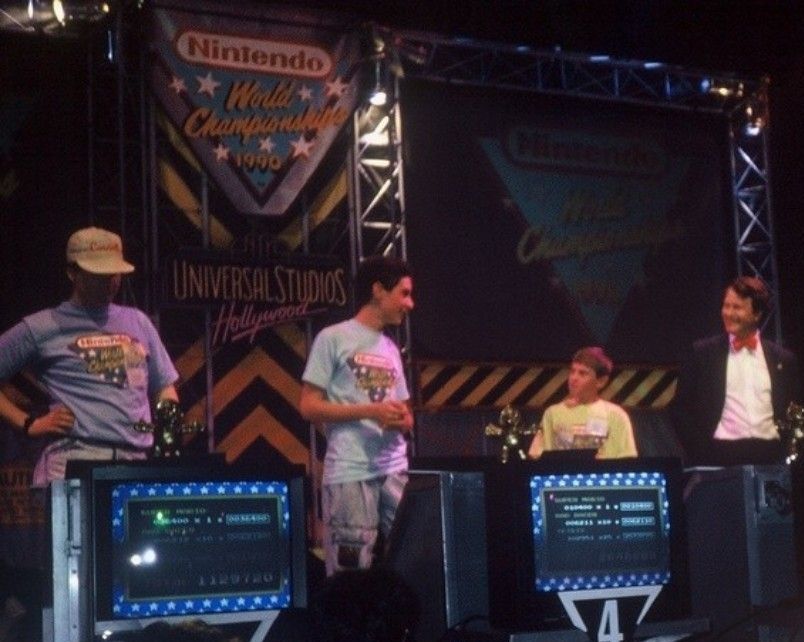

This fumble was happening against the backdrop of a market suffocated by success. By 1989, Nintendo wasn’t just a company, it was the entire ecosystem. The shelves of every toy and electronics store were a monolithic wall of gray NES cartridges. While this saturation represented total market dominance, it also bred a subtle fatigue. Gamers were growing restless in the Mushroom Kingdom. They were hungry for a real leap forward, a true generational shift that Nintendo, still riding the high of its 8-bit success, seemed in no hurry to provide.

The landscape was littered with countless uninspired licensed games and platformer clones. For the older kids, the ones who were graduating from Saturday morning cartoons to MTV, the NES was starting to feel like yesterday’s news. The kingdom was prosperous and peaceful but it was also predictable. The conditions were perfect for a revolution. The market wasn’t just ready for a challenger, it was desperate for one.

Despite a challenging start in Japan and facing Nintendo’s seemingly unshakeable dominance, Sega’s Genesis carved its path into the North American market by strategically exploiting the missteps of rivals like the TurboGrafx-16 and by recognizing a growing hunger for something new among an increasingly mature gaming audience. It was a calculated and audacious move, leveraging a powerful new console and a rebellious marketing approach to ignite a console war that would forever change the industry.

Genesis Does What Nintendon’t

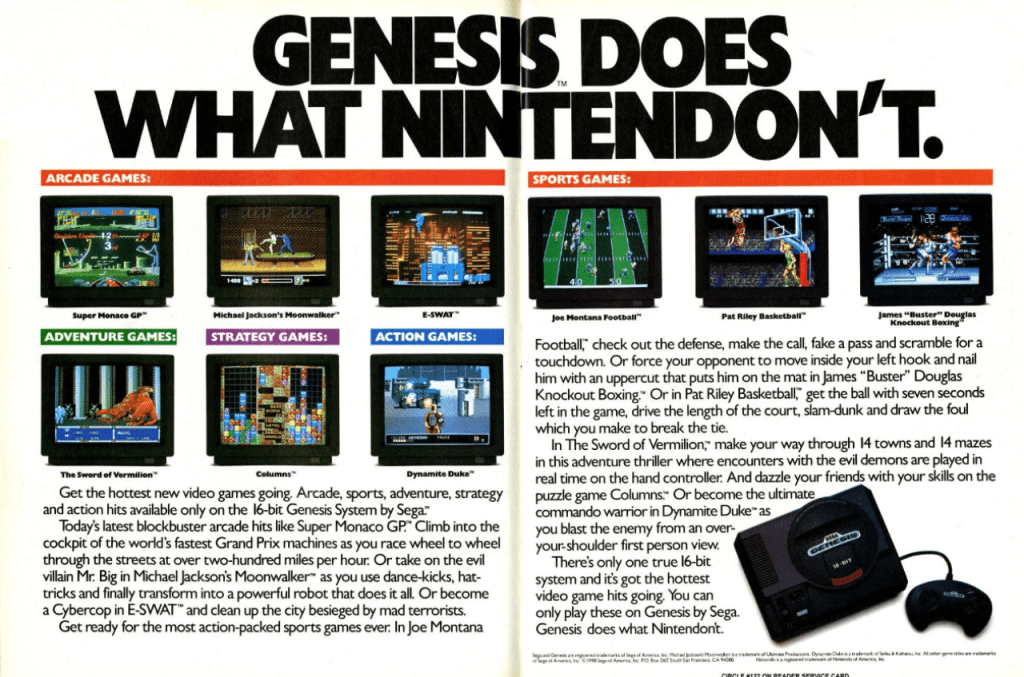

A great machine and a few great games were a start, but Sega knew they needed to fight a war of perception. Under the guidance of new Sega of America CEO Michael Katz and marketing head Al Nilsen, the company unleashed a marketing blitz that was as audacious as it was brilliant. They crafted a slogan that became a schoolyard rallying cry, a direct, taunting challenge to the undisputed king: “Genesis does what Nintendon’t”.

This was unheard of. In an era of polite, feature-focused advertising, Sega threw a punch. Their commercials were a masterclass in comparative marketing, relentlessly showing the vibrant, detailed, 16-bit graphics of Genesis games side-by-side with the blocky, dated visuals of the 8-bit NES. The message was simple, brutal, and effective: we are the future, they are the past.

The strategy was genius. They knew they couldn’t win by competing for the hearts of the 6-to-12-year-olds that Nintendo owned. Instead, they targeted their older siblings. They went after the teenagers, the kids who hung out in arcades and thought Nintendo was for babies. The marketing, the black console, the edgier games, it all worked together to cultivate an image of Sega as the cool, rebellious older brother to Nintendo’s squeaky-clean persona. By the end of its first year, Sega had sold half a million consoles. While short of their internal goal of a million, it was a monumental success. It shattered the myth of Nintendo’s invincibility and established a vital beachhead in the market. The console war had begun.

A New Beginning

Looking back, the launch of the Sega Genesis was so much more than the arrival of a new piece of hardware, it was a declaration that the video game industry was big enough for a real fight and that competition would breed an incredible era of innovation and creativity. Sega, born from the ashes of the Master System’s failure, forged a new identity built on arcade power, strategic marketing and a healthy dose of attitude.

The Genesis was not just a machine, it was a statement. It made gaming cool for a whole new generation and kicked off the most exciting and fiercely competitive decade in the history of the medium. For those of us who were there, who heard that first gravelly growl and felt the promise of that black box, the memory of that moment will never fade.

Leave a comment