The Weekend Rental That Changed Everything

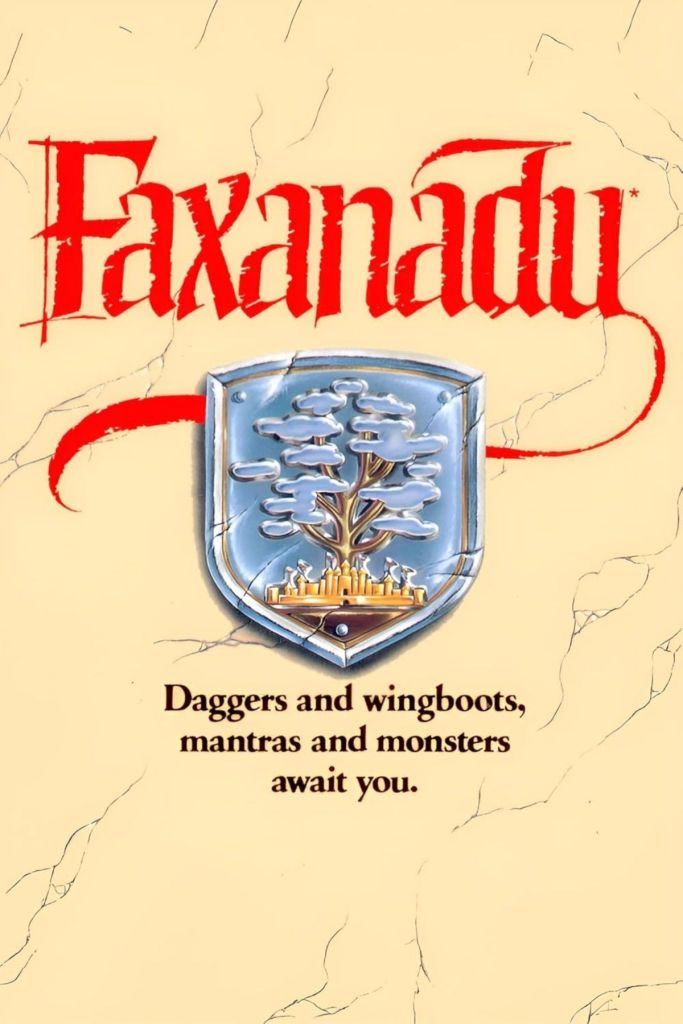

There it was on the video store shelf, standing out in a sea of explosive action scenes and cartoon mascots, a simple box, with a single, mysterious word emblazoned across the front: Faxanadu! The box was designed like a slab of cracked, ancient parchment, immediately setting it apart from its colorful peers. It drew the eye to a shimmering, metallic blue crest that dominated the cover, inside of which stood a stylized silver tree sheltering a tiny golden city at its roots. Adorned with one single sentence it sold you on a world, promising a solemn journey into a land of ancient magic and deep history before you ever pressed the power button.

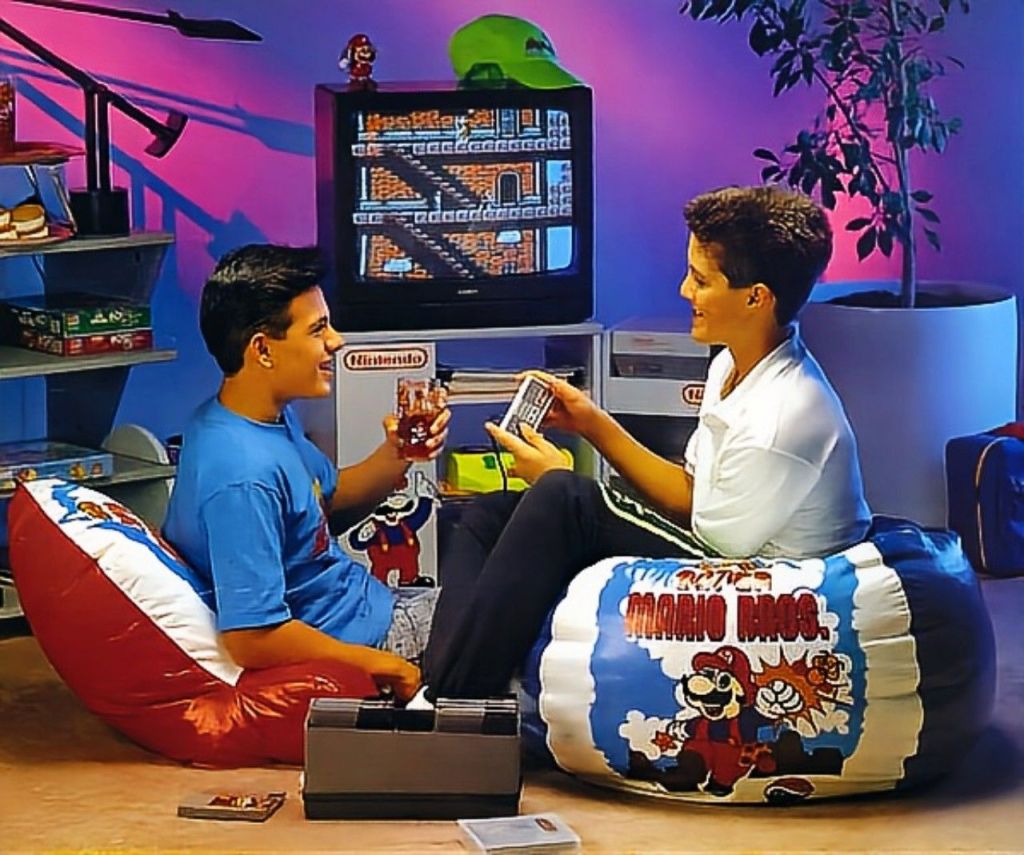

It didn’t scream fun, but you could feel that there was an epic journey in that box. For a kid navigating that aisle, powered by the promise of a weekend rental, this brown box was an easy sell. It promised something more immersive than anything else sitting on that shelf. A promise delivered the moment you slid the cartridge into the NES, pressed power, and the hum of the CRT television was joined by an unforgettable and utterly perfect melody as you set off on your adventure towards the World Tree.

Dragon Slaying Our Way to the World Tree

To truly understand the strange, wonderful, and almost accidental soul of Faxanadu, you must travel back to a different world of gaming. Forget the living room floor and the 8-bit console for a moment. Instead, picture the buzzing, innovative, and decidedly more niche landscape of 1980s Japanese PC gaming. This was the domain of Nihon Falcom, a developer that was fundamentally shaping the future of role-playing games on powerful home computers like the NEC PC-88. While Japanese console gamers were just getting their first taste of Hyrule, Falcom was already building sprawling, complex worlds for a dedicated, hardcore audience.

In 1984, fed a steady diet of turn-based Western RPGs like Ultima and Wizardry, a brilliant Falcom designer named Yoshio Kiya decided to shatter the mold. He envisioned a game that combined the deep exploration and character progression of an RPG with the immediate, visceral thrill of an arcade game. The result was Dragon Slayer, a title that single-handedly birthed the action RPG genre as we know it today. It was a revolution, introducing the concept of real-time combat where you physically moved your character into enemies on screen to attack. It was fun, it was like nothing that came before, and it was a smash hit. But the Dragon Slayer name was never meant to be a single, continuous story. It became Falcom’s banner for relentless experimentation, a series where each new installment would be a radical reinvention of the last, often by different design teams.

It was a revolution, introducing the concept of real-time combat where you physically moved your character into enemies on screen to attack. It was fun, it was like nothing that came before, and it was a smash hit. But the Dragon Slayer name was never meant to be a single, continuous story. It became Falcom’s banner for relentless experimentation, a series where each new installment would be a radical reinvention of the last, often by different design teams.

This philosophy is what led to the 1985 PC blockbuster, Dragon Slayer II: Xanadu. If the original Dragon Slayer was the proof of concept, Xanadu was the magnum opus. It was a cultural phenomenon in Japan, selling an astonishing 400,000 copies and becoming a benchmark for the genre. It was a massively complex side-scrolling epic with deep, demanding mechanics. Players had to manage a depleting food supply, contend with a Karma system that judged which monsters they killed and navigate a sprawling, interconnected world. Your character’s sprite even changed to reflect the armor and weapons you equipped, a groundbreaking feature for the time.

The reach of these games was immense, going on to influence later series such as The Legend of Zelda, Hydlide, and Falcom’s own Ys. Given their monumental success, a console adaptation for Nintendo’s white-hot Famicom seemed not just inevitable, but necessary.

A Console Rebirth

In the business ecosystem of the 1980s, Nihon Falcom was a PC developer first and foremost. For the burgeoning console market, they typically licensed their valuable properties to other, more experienced console developers. The task of cramming the sprawling, complex world of Xanadu onto a humble Famicom cartridge was given to the talented team at Hudson Soft, a company already renowned for its technical mastery of Nintendo’s hardware. The deal was struck, the license was granted, and Hudson began advertising the game as a faithful port of the PC classic. But what happened next was not just a port, it was an act of creative rebellion.

The project’s lead designer at Hudson, Hitoshi Okuno, had such a bad impression of Xanadu’s intricate systems that he questioned its viability for a console audience. How could you translate a game that demanded a keyboard, a dedicated player, and hours of focused attention into something a child could pick up and enjoy on a Friday night? Okuno believed that its demanding PC mechanics, the karma system, the need to keep your hero fed and the overly complex stats would completely alienate the Famicom audience. So, he threw almost all of it away.

In a move that angered Nihon Falcom, Okuno and his team kept only the core essence of the game: the theme of exploring a vast, dying, world and the deeply satisfying loop of finding better gear to make your character stronger. They built an entirely new game on this spiritual foundation, a game they bluntly titled Faxanadu—a combination of Famicom and Xanadu, a declaration of its new identity. By the time Falcom realized how radically different Hudson’s version was, development was too far along to force a change.

The licensing agreements of the era were often less creatively restrictive than they are today, giving the licensee significant leeway. The relationship between the two companies was strained, but the game was a reality. Hudson had not simply ported a game, they had created something entirely new, an act that, ironically, was perfectly in keeping with the Dragon Slayer series’ own ethos of radical reinvention.

Getting to the Root of the Action RPG

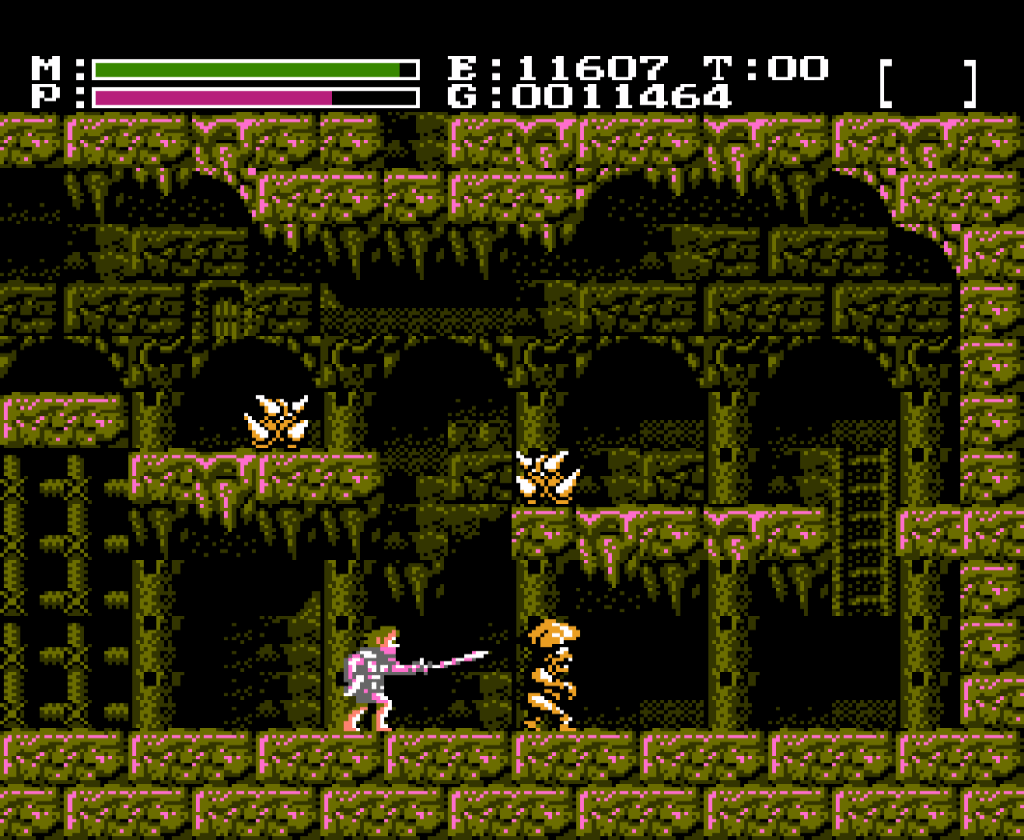

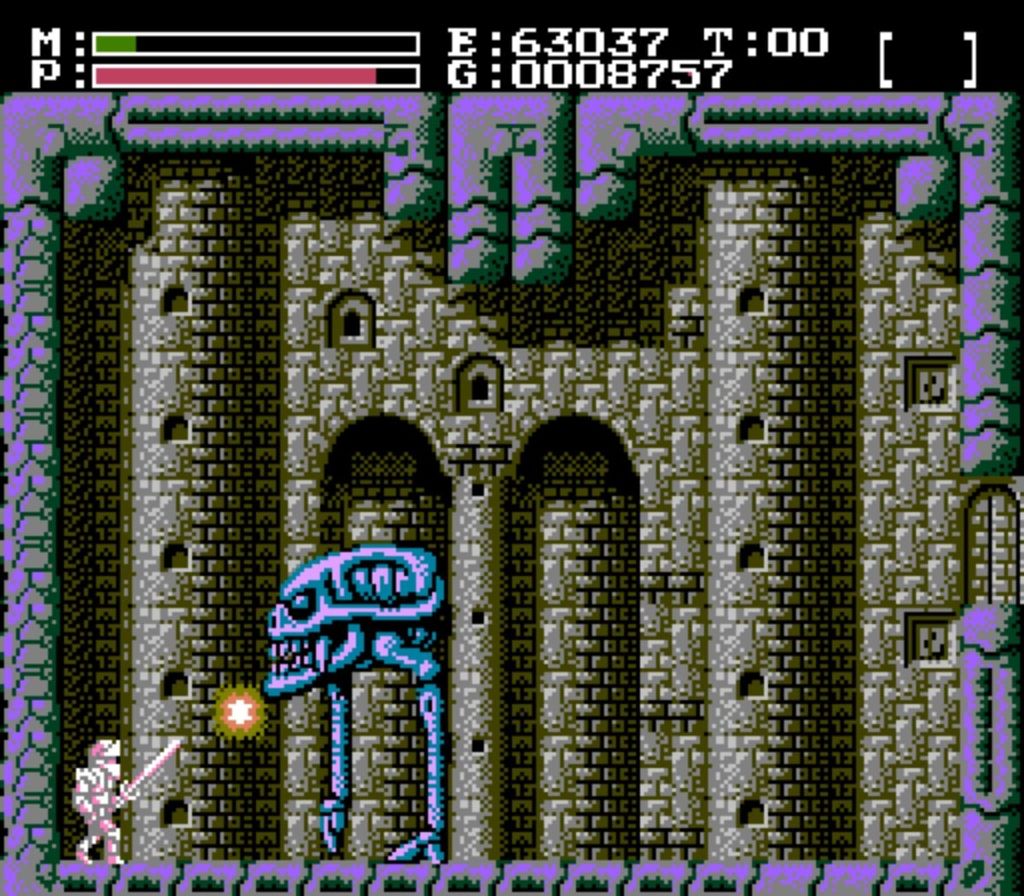

Playing Faxanadu today is an exercise in appreciating the limitations of 8-bit game design circa 1989. Combat is a simple, methodical affair: one button thrusts your sword one button jumps. Your inability to duck limits your ability to handle low-crawling enemies, a design limitation that elevated your limited magic from a novelty to a tactical necessity. Your jumps are committed and stiff, with almost no ability to correct your course in mid-air. This wasn’t a flaw, it was a choice. Every leap across a chasm felt like a commitment, every step into a new screen filled with a palpable sense of caution. This wasn’t the lightning-fast action of Ninja Gaiden, it was a slow, considered, and deeply atmospheric climb.

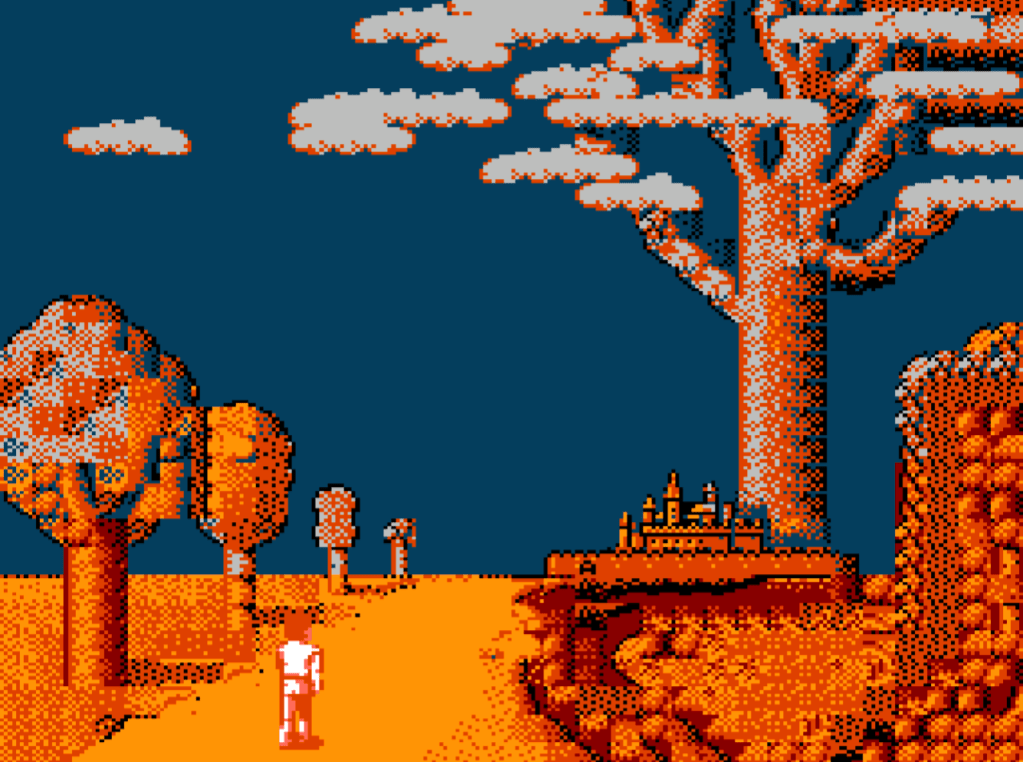

But what truly cements Faxanadu in the annals of gaming history, the element that burns brightest in our collective memory, is its peerless and oppressive atmosphere. In an era dominated by cheerful primary colors, Hudson made the audacious choice to paint its entire world almost exclusively in shades of brown, grey, and murky green.

The whole of the game takes place within the roots, trunk, and branches of a single, colossal, dying World Tree, a brilliant concept that gives the world a stunning sense of cohesion and verticality. You feel like you’re truly ascending a dying behemoth. The air itself seems thick with decay, an atmosphere enhanced by bizarre, almost H.R. Giger-esque enemy sprites that look like nothing else on the NES. These pulsating, alien creatures were a far cry from the cute Goombas and Octoroks of other games.

This bleak visual tapestry is woven together by Jun Chikuma’s incredible chiptune score. The music is adventurous and moving, a masterwork of melody that squeezed an impossible amount of richness and emotion out of the console’s limited sound chip. The main theme’s call to adventure, the hopeful town melody, and the tense but determined boss battle track are all as much a character in the game as the hero himself.

Forging New Paths in Action RPGs

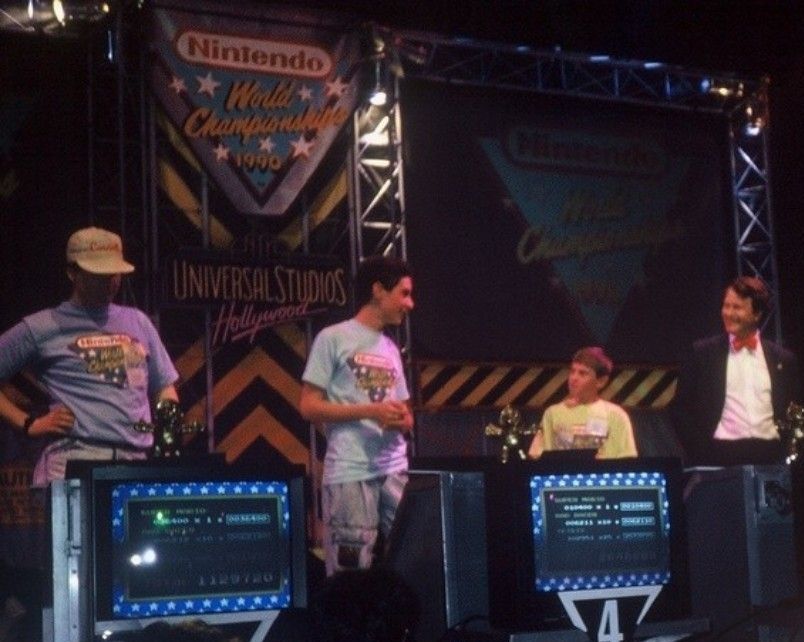

Upon its North American release in 1989, Faxanadu was a critical and commercial success, debuting at number six on Nintendo Power’s December Top 30 list and staying on the charts for months. While it never spawned a direct sequel or a massive franchise, its reputation as the quintessential hidden gem has only grown stronger over the decades.

Its legacy is not just that of a great game, but of a fascinating historical artifact. Faxanadu is the product of a contentious but ultimately fruitful development process, a story of creative vision triumphing over contractual obligation. It represents a perfect collision of two distinct gaming philosophies: the complex, system-heavy world of Japanese PC RPGs and the more streamlined, action-focused demands of the console market. It is a game that could only have been born from a developer taking a bold, rebellious risk with a licensed property, choosing to interpret its spirit rather than its letter.

The slow, methodical climb up the dying World Tree, the simple satisfaction of buying that next suit of armor, the adventurous melody that greets you in a new town, these are the memories that endure. Faxanadu wasn’t just a game in a simple beige box, it was a journey to an ancient world. It was a masterpiece of mood, an accidental classic that has more than earned its place in the 8-bit pantheon.

Leave a comment