The Beginning of the End for Nintendo’s Empire

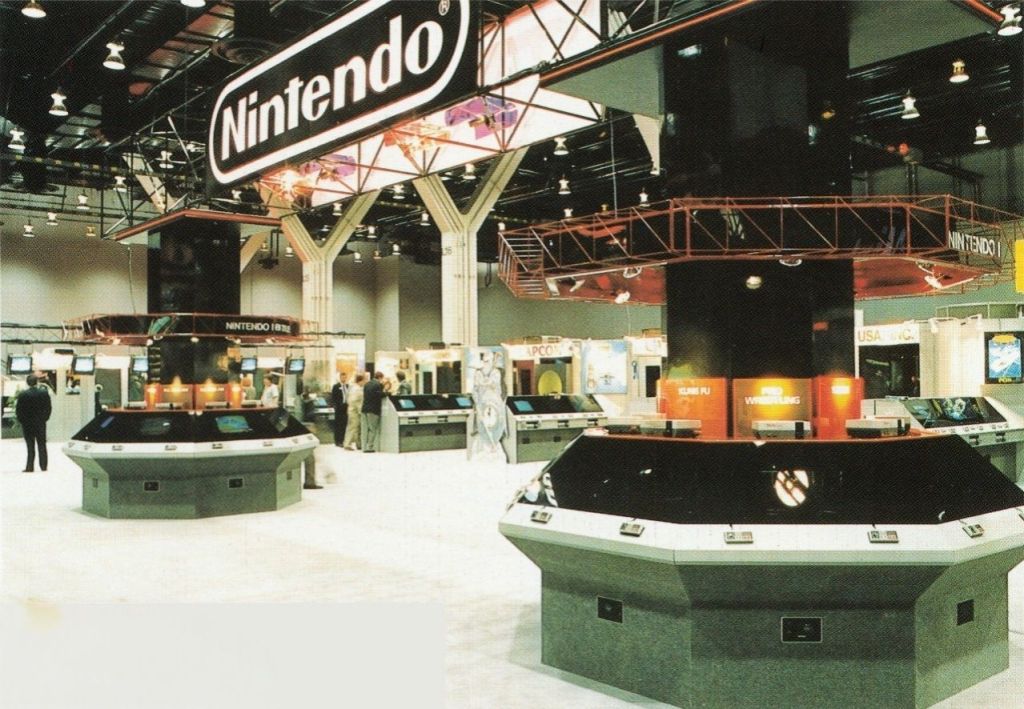

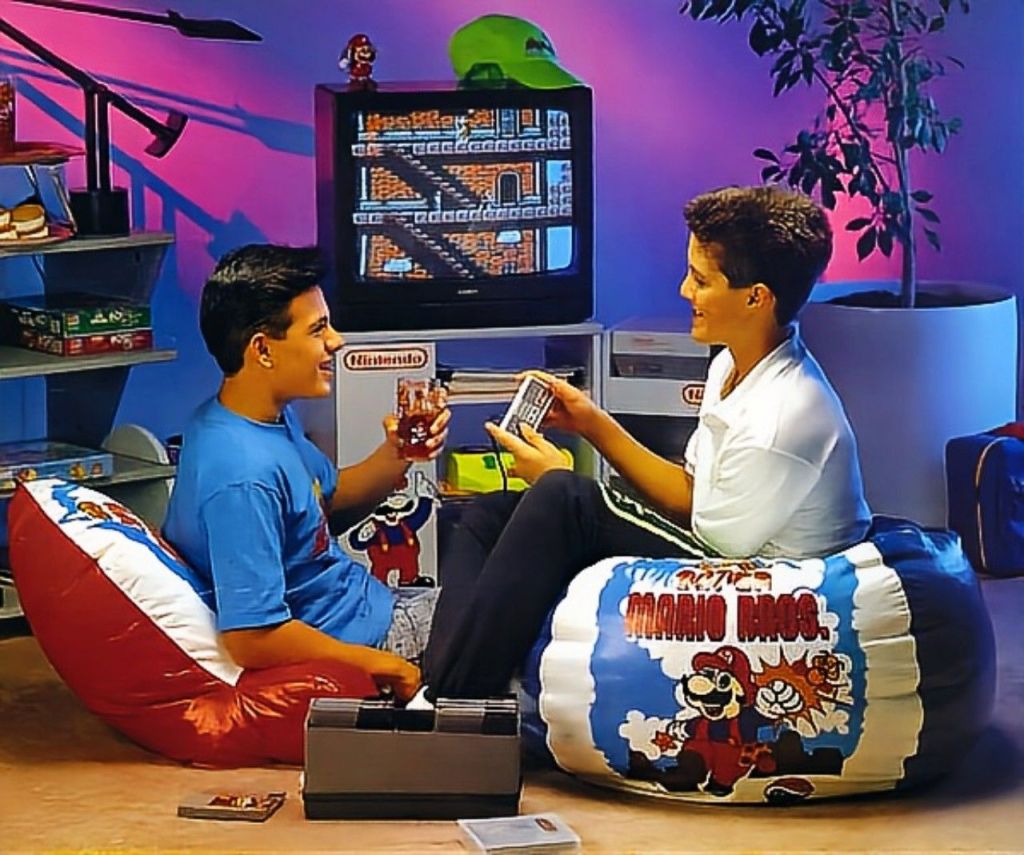

It’s the summer of 1989. Tim Burton’s Batman ruled the box office, Saved by the Bell had just premiered on our televisions and McDonalds was in the middle of another one of its ill-fated attempts to sell us fast food pizza. In the world of video games, one name reigned absolute: Nintendo. The grey NES box wasn’t just a toy, it was a cultural fixture, an appliance as essential as the family television it was perpetually hooked up to. Nintendo felt like an empire; permanent, unshakeable, and destined to last forever.

But even the most enduring empires can fall. Beneath the surface of this undisputed 8-bit dominance, a seismic shift was rumbling. Two powerful challengers from Japan, armed with futuristic technology and arcade-forged ambition, were just weeks away from landing on American shores. They promised nothing less than a 16-bit revolution for the living room, a quantum leap in graphics and sound that would change everything.

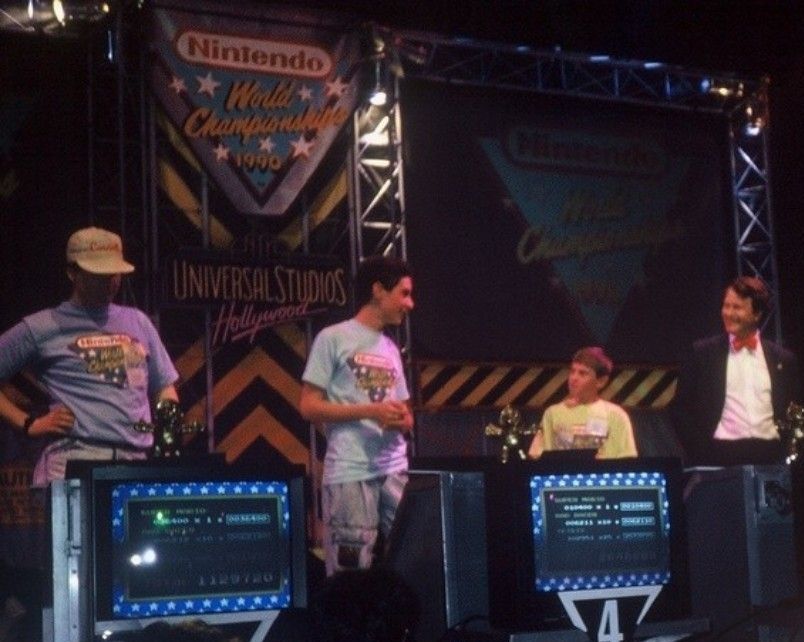

This would be the last peaceful summer before the console war began—a time when the 8-bit era’s creative genius clashed with the raw, untamed, power of the 16-bit future that was just over the horizon. For the kids following the mag coverage at the time, the hype was unbearable!

The Press Draws Its Battle Lines

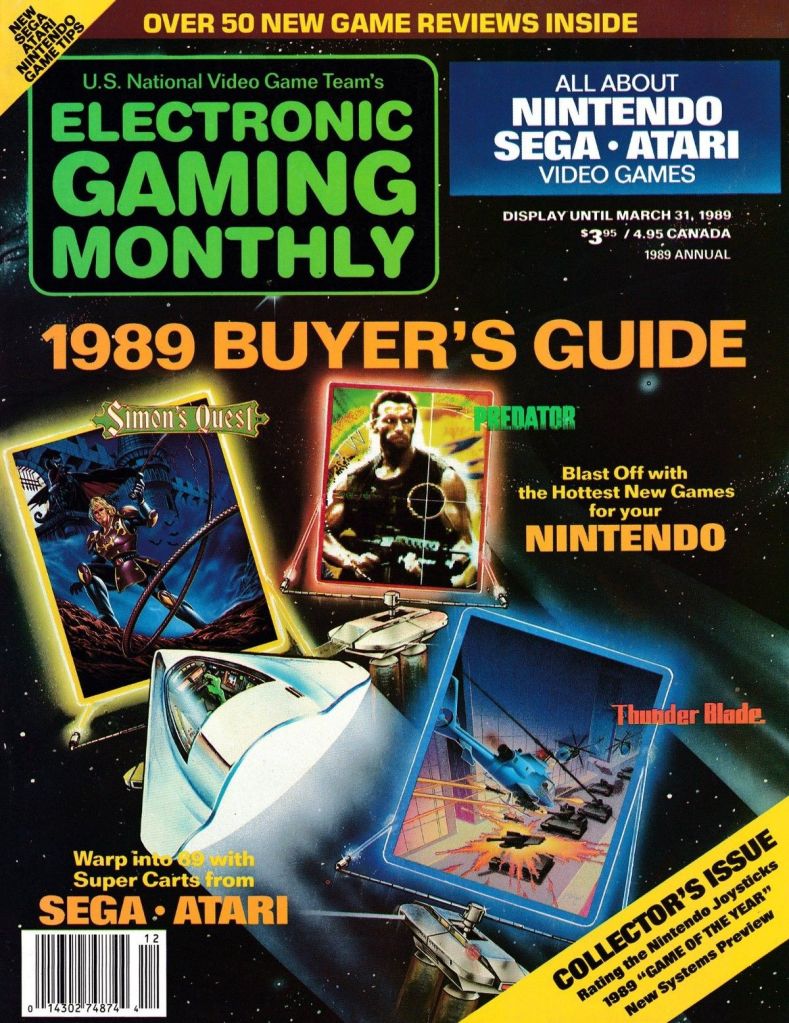

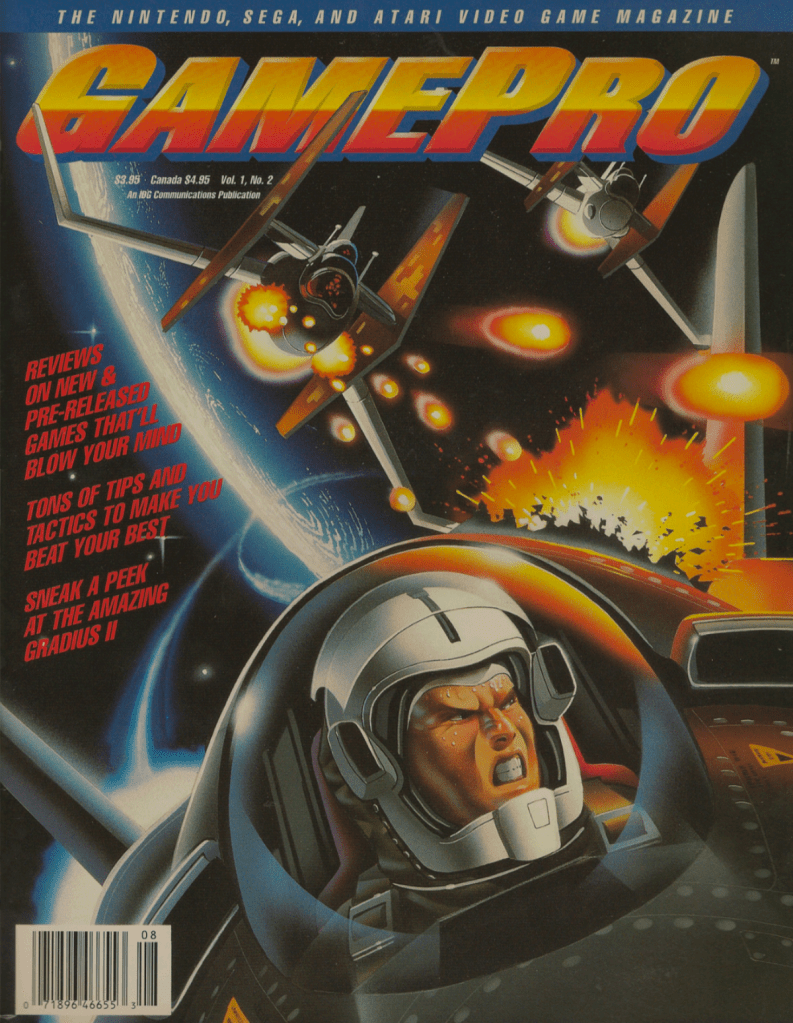

As the 16-bit titans prepared for battle, the magazines that covered them were busy drawing their own lines in the sand.

On one side stood the upstarts. In just its second issue, EGM was positioning itself as the serious, discerning voice for the burgeoning hardcore gamer. Editor Steve Harris’s Insert Coin column was a mission statement, a thinly veiled shot across Nintendo Power’s bow promising unbiased reviews and numerical scores. The very layout of EGM was a radical act of rebellion, giving Sega, NEC, and Nintendo equal real estate on its pages was a declaration that the world was bigger than the Mushroom Kingdom. EGM was the know-it-all older brother who treated gaming less like a toy and more like an art form worthy of serious critique.

Then there was GamePro. With its colourful pages, cartoon reviewer avatars, and ProTips, GamePro was the cool, rebellious friend who had all the top scores at the local arcade. Their “You Asked For It, You Got It” philosophy was a direct appeal to the gamer who felt left out by Nintendo’s iron-fisted reign. By explicitly promising more coverage for Sega than any other magazine, they weren’t just filling a niche, they were making a cultural alignment, a bet on the underdog that would pay off in spectacular fashion.

And what of the empire? Nintendo Power celebrated its one-year anniversary not as a magazine, but as a direct line from the gods on Mount Nintendo. It wasn’t just a source of information, it was the source. Its power came from its official status: guaranteed secrets, developer interviews, and perfectly drawn maps that were the holy grail of the schoolyard. You trusted Nintendo Power implicitly, and that trust came with an understanding of its inherent bias. It was the imperial decree, and for millions of kids, it was the only voice that mattered.

The 16-Bit Hype Machine

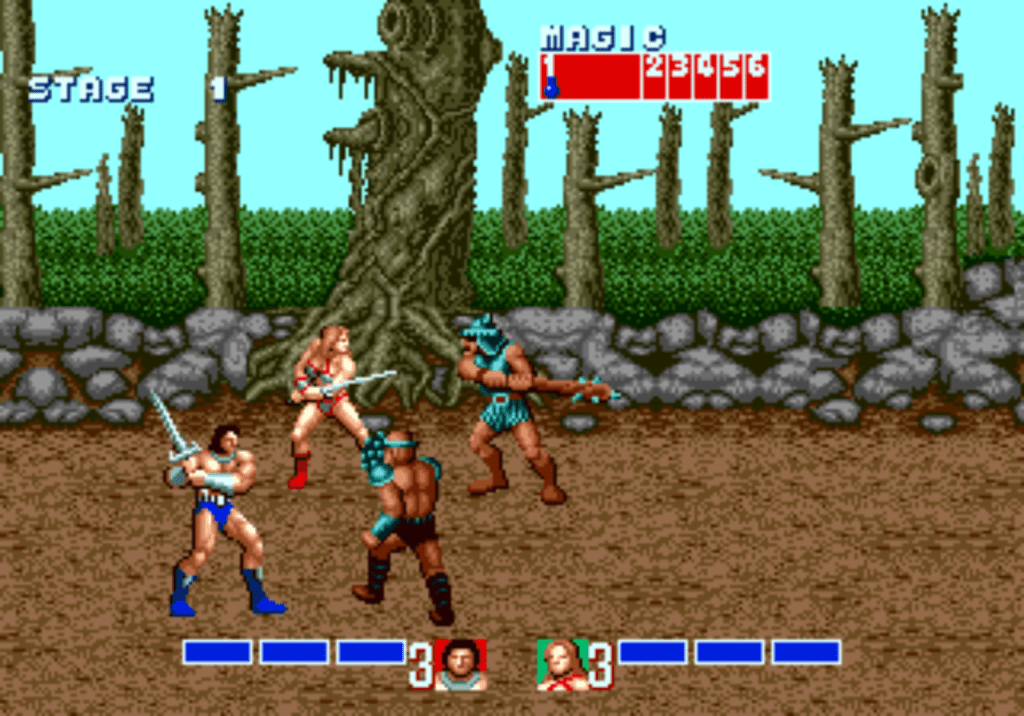

While the magazines jostled for position, they all agreed on one thing: the future was 16-bit and the anticipation was at levels we’d never seen before. To understand why, you have to remember the chasm that existed between the arcade and the home in 1989. The arcade was a magical, noisy dimension of impossible graphics. It was the thundering bass of Golden Axe’s soundtrack, the fluid animation of Strider, the screen-filling bosses of Ghouls ‘n Ghosts. The NES ports of these games were brave, often brilliant, but they were ultimately compromised translations. The 16-bit promise was that this gap, this chasm between dream and reality, was about to disappear forever.

Leading the charge was the Sega Genesis. It looked like something from the future: sleek, black, and adorned with a glorious “16-BIT” in bold font lettering right on the front, just in case you missed the memo. It was marketed as the cool, edgy alternative to Nintendo’s family-friendly box. This was the console your parents might not understand, and that was precisely the point.

Its pack-in game, Altered Beast, was a masterstroke of marketing. The gameplay is clunky today, but in 1989, it was a profound statement. The massive, transforming sprites and the gravely, digitized speech that commanded you to “Rise from your grave!” were a world away from anything the NES could produce. It was a visceral demonstration of power, a punchy, two-player arcade brawler that let everyone know that home gaming would never be the same. The magazines fanned the flames, showing off screenshots of a near-perfect port of Ghouls ‘n Ghosts and the neon drenched alien landscapes of Space Harrier II, cementing the Genesis as the arcade veteran’s dream machine.

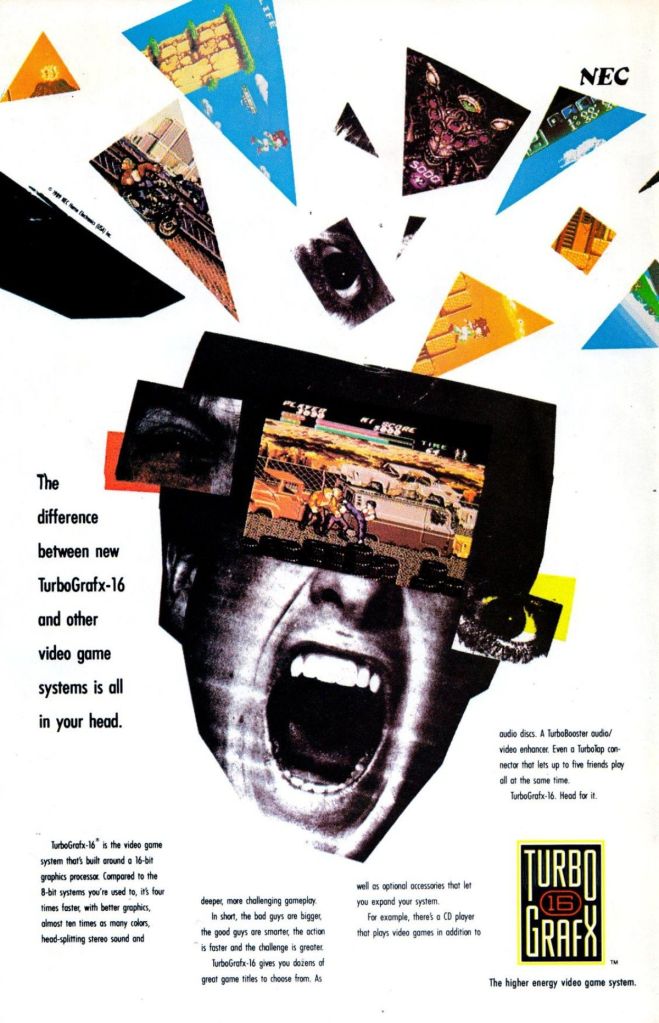

The other challenger was the sleeker, more futuristic looking, TurboGrafx-16 console. The machine was a powerhouse, already a massive hit in Japan as the PC Engine. But its American launch was quirky. The pack-in game was Keith Courage in Alpha Zones, a generic and utterly forgettable platformer-RPG hybrid. Compared to the immediate arcade cred of Altered Beast, Keith Courage was a baffling choice that left many potential fans scratching their heads.

Yet, the magazines showed there was magic to be found if you looked closer. Titles like the critically acclaimed Legendary Axe and the mesmerizing pinball simulation Alien Crush hinted at the system’s true potential. The TG-16 was quickly framed as the connoisseur’s choice, a machine with hidden gems for those willing to venture off the beaten path.

Nintendo’s 8-Bit Masterworks

While Sega and NEC were busy selling the future, Nintendo and its partners were perfecting the present. The company’s response to the 16-bit threat wasn’t a new console—the SNES was still a year away for Japan and even further for America. Instead, Nintendo unleashed a software blitz of such unparalleled quality that it served as a defiant roar, proving the old grey box still had plenty of magic left in it. The summer issue of Nintendo Power was a monument to the games that represented the creative peak of the 8-bit era.

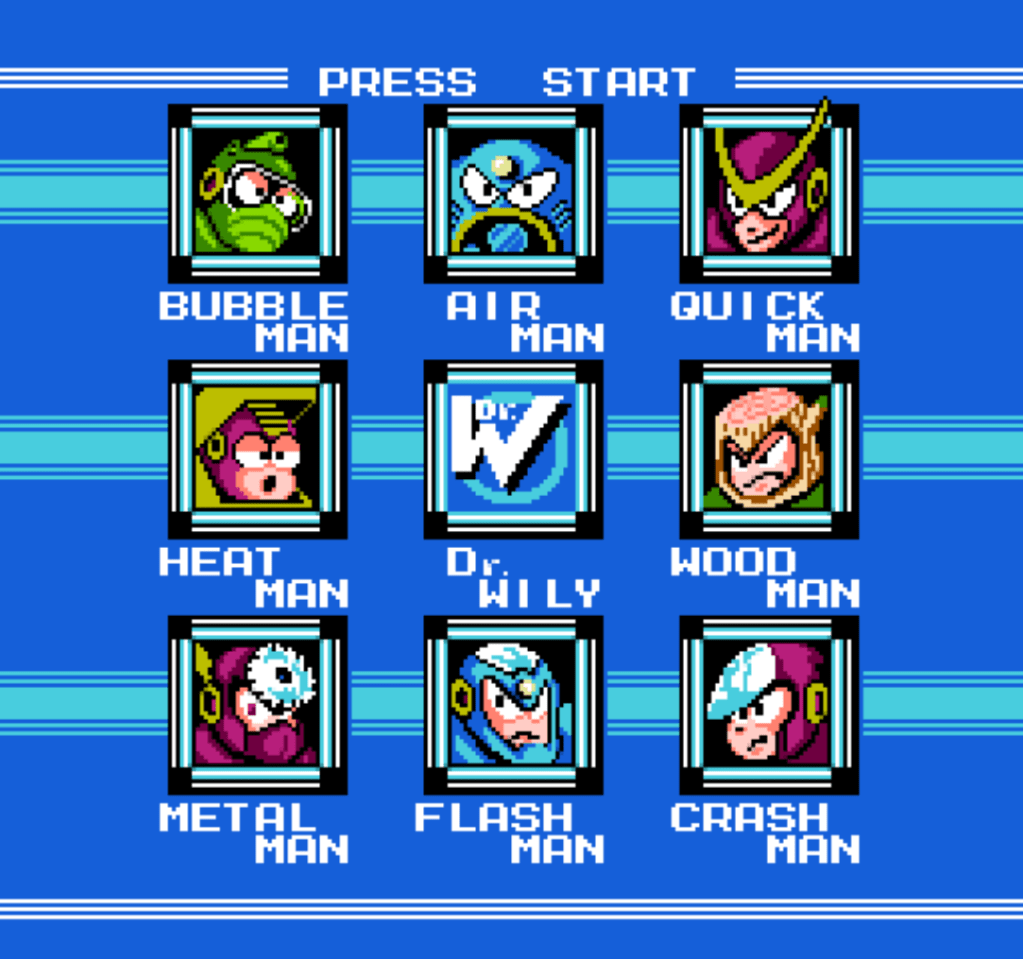

There are sequels, and then there is Mega Man II. The first game was a modest, brutally difficult hit. The second was a masterpiece. From the moment you pressed start and that iconic theme kicked in as the Blue Bomber stood atop a skyscraper, you knew you were in for something special. The game refined every concept from its predecessor to near-perfection. The choice of eight Robot Masters offered a non-linear path through the game, creating a strategic puzzle before you even fired a shot. And the music! The tracks weren’t just background noise, they were 8-bit symphonies, complex, driving, and unforgettable anthems for a generation of gamers. The core loop of defeating a boss, absorbing their power, and using it to exploit another’s weakness was pure design genius. And let’s be honest, there has never been a more satisfyingly overpowered weapon in gaming history than Metal Man’s Metal Blade. Mega Man II wasn’t just a great game, it was a flawless blueprint for action-platforming.

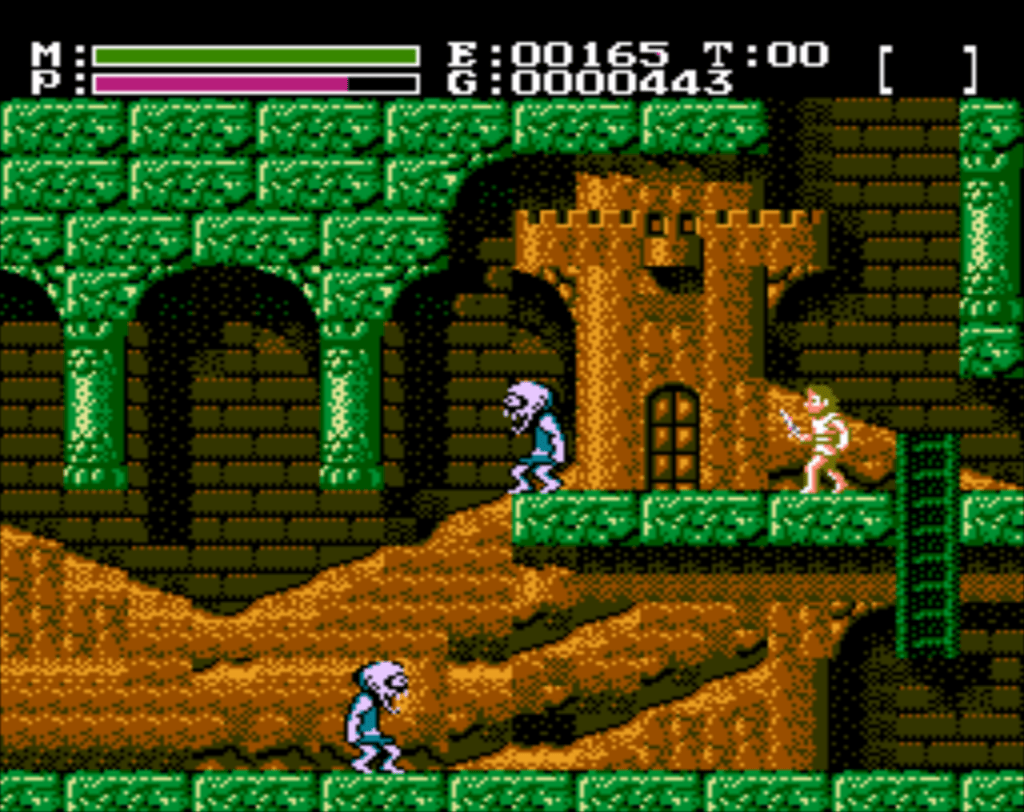

In a sea of bright, cheerful platformers, Faxanadu was the weird, brown, and wonderful adventure you never knew you needed. A spin-off from the Japanese RPG series Xanadu, it was unlike anything else on the NES. Its muted, earthy color palette and haunting, melancholic soundtrack created an atmosphere of oppressive dread and ancient mystery. You weren’t a superhero, you were a nameless wanderer returning to your dying hometown, armed with little more than a dagger and a few gold coins. The game was a true adventure. You’d talk to a townsfolk who would give you a cryptic clue, use your savings to buy a key from a shady merchant, and venture into the labyrinthine World Tree, fighting bizarre monsters on your way to the next town. The sense of progression—of slowly transforming from a weak nobody into a powerful, armor-clad hero—was immense. Faxanadu didn’t hold your hand, it dropped you into its dying world and trusted you to find your own way.

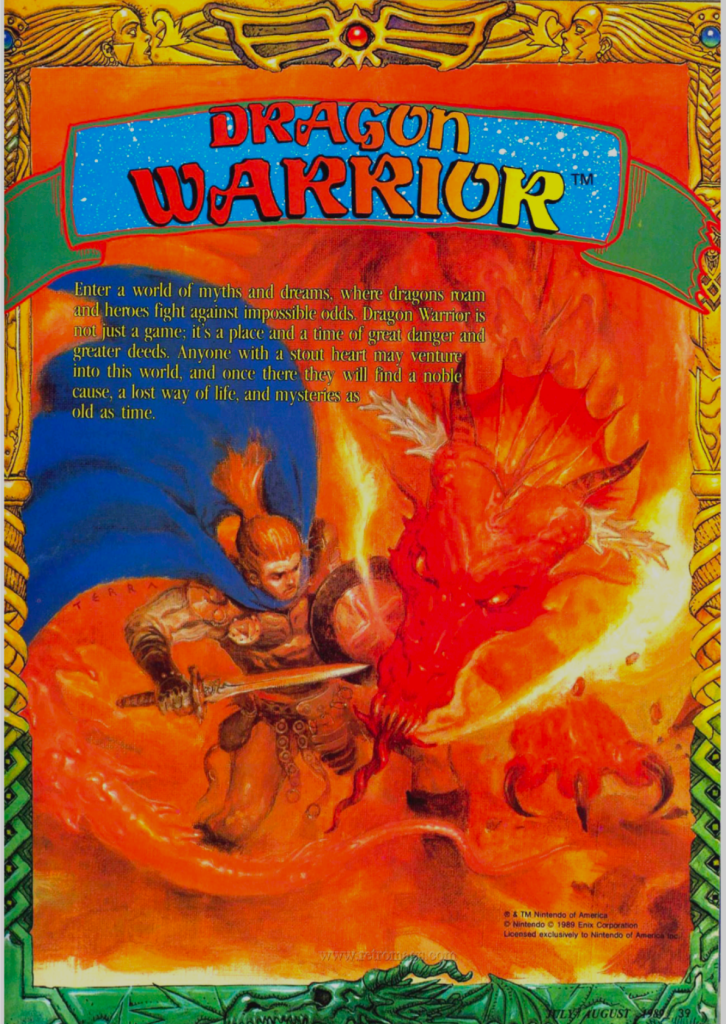

As one of the first RPGs to hit consoles in the West, It is impossible to overstate the importance of Dragon Warrior. In Japan, the Dragon Quest series was a national obsession. In North America, console RPGs simply didn’t exist, they were the complex, stat-heavy domain of PC gamers. Dragon Warrior was sent as an ambassador, and its mission was to teach an entire continent a new way to play. The gameplay was deliberate, methodical, and for many, revolutionary. The concept of grinding—fighting monster after monster to earn experience points and gold—was a rite of passage. Do you remember the sheer terror of wandering too far from Tantegel Castle, getting lost, and being wiped out by a Goldman? Do you remember the feeling of triumph after hours of fighting Slimes just to finally afford the Copper Sword? This was a game that demanded patience and rewarded it with a true sense of accomplishment and a massive world to explore.

The summer of 1989, then, wasn’t just business as usual for Nintendo. It was a defiant flourish, a testament to the fact that creativity, honed by limitation, could still produce unparalleled experiences. While the roar of 16-bit machines was growing louder, the NES, in its twilight, proved it was still capable of delivering timeless adventures that would forever define a generation’s understanding of what a video game could be.

The Turning Point

The summer of 1989 was a unique crossroads in gaming history. It was a perfect storm where the absolute creative zenith of the 8-bit era, embodied by the design masterpieces of Mega Man II and Dragon Warrior, collided with the raw, untamed technological promise of the 16-bit future. The games being celebrated on the NES were art, honed to perfection within strict limitations. The games being hyped for the Genesis and TurboGrafx were powerful, promising to shatter those limitations entirely.

The promises had been made, the hype had reached a fever pitch, and the magazines had chosen their sides. The last peaceful summer was over. The console war had begun.

Mag Coverage

Leave a comment