A Horror Emerges from the Void of the Cosmos

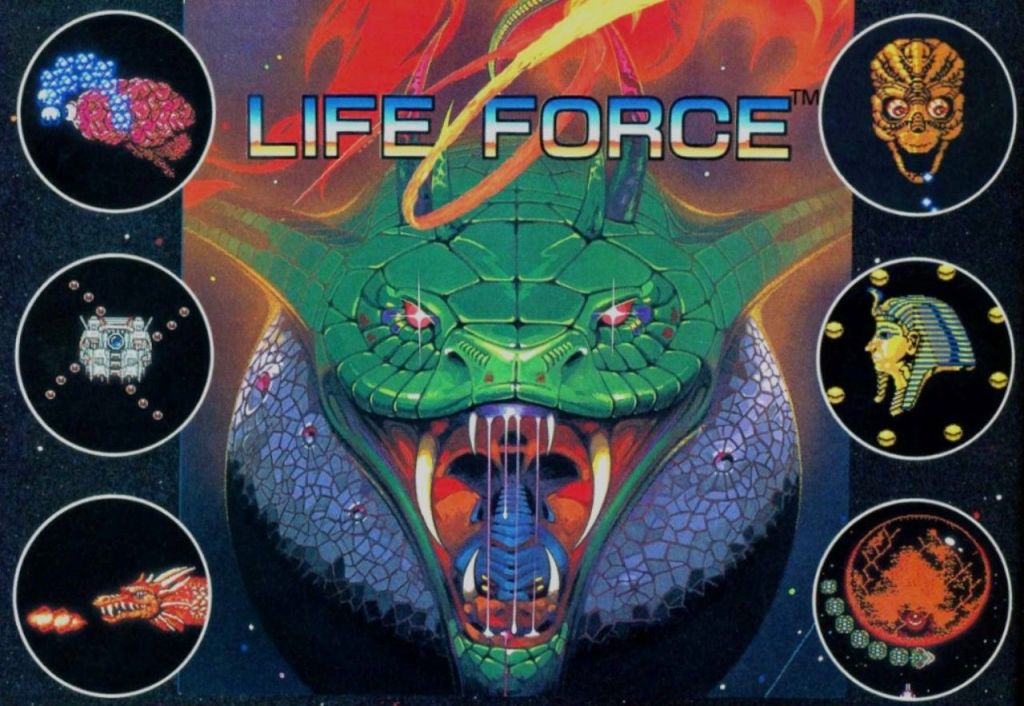

Two years of fragile peace had settled over the planet Gradius. The war against the Bacterian star system was a fading memory, a hard-won victory that echoed only in old flight logs and memorials. Then, the alarms screamed. A new crisis. An unprecedented threat that blotted out the stars. It was not a fleet of ships. It was a single, unknown super-organism, a colossal entity the astronomers dubbed Life Force. This gigantic creature absorbed all matter in its path, growing endlessly as it devoured entire worlds. Its trajectory was set. Planet Gradius would be consumed.

With all hope nearly lost, the call went out for one last desperate mission. The hangar doors slid open, revealing the sleek frame of the super spatio-temporal fighter, the Vic Viper. Your mission was unlike any other. You would not simply attack this planet-devouring alien. You had to fly directly inside the belly of the beast to destroy it from within.

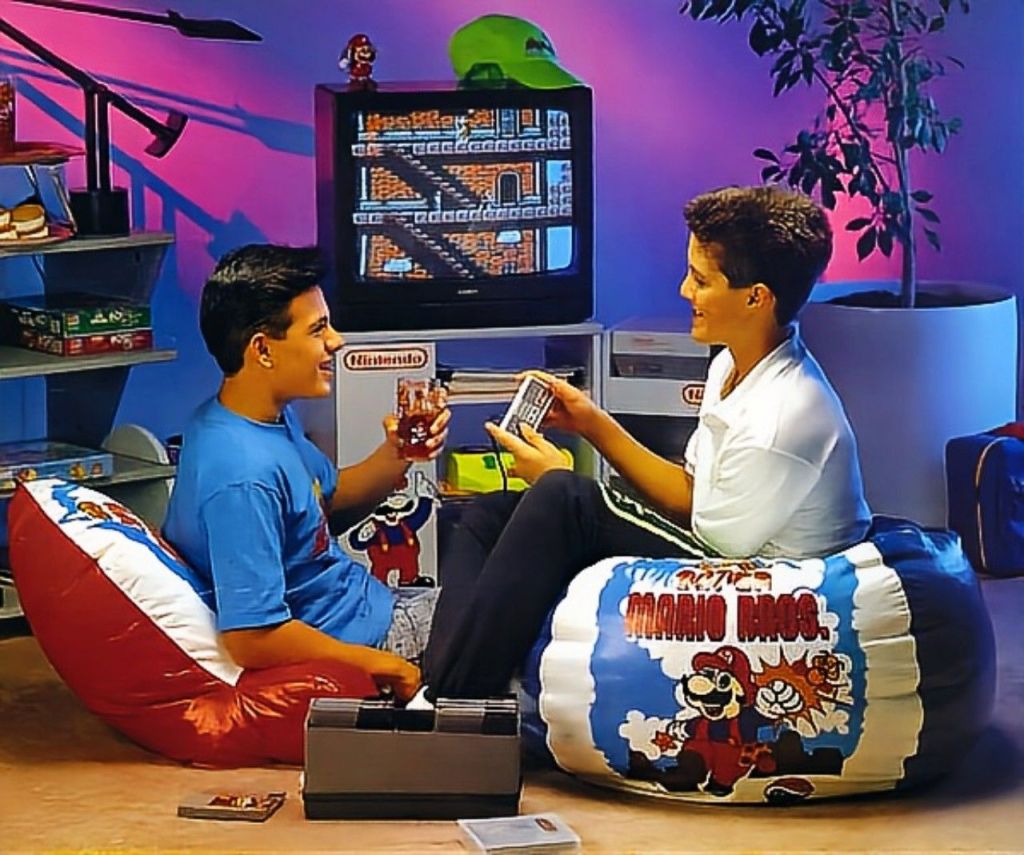

This was not just another game. This was Life Force. For countless kids in the late 80s, this was the moment the genre of the space shooter was perfected. It was a game that demanded a second player, a game whispered about on the schoolyard, a game that swallowed you whole and dared you to shoot your way out. It was a journey into the grotesque, a symphony of pixelated explosions, and the definitive cooperative experience of its time.

The Gradius Strain

To understand the lightning in a bottle that was the NES version of Life Force, you have to rewind to 1988 and take a look at the gaming landscape. The NES was an unstoppable juggernaut, and Konami was one of its master craftsmen. We had all cut our teeth on their 1985 masterpiece, Gradius. It was a brilliant but punishing side-scrolling shooter that established the iconic power-up bar. Yet, for all its greatness, it was a solitary and often brutal affair. We were hungry for more, and for those of us in North America, the official sequel, Gradius II, never made it to our 8-bit consoles. We needed a successor.

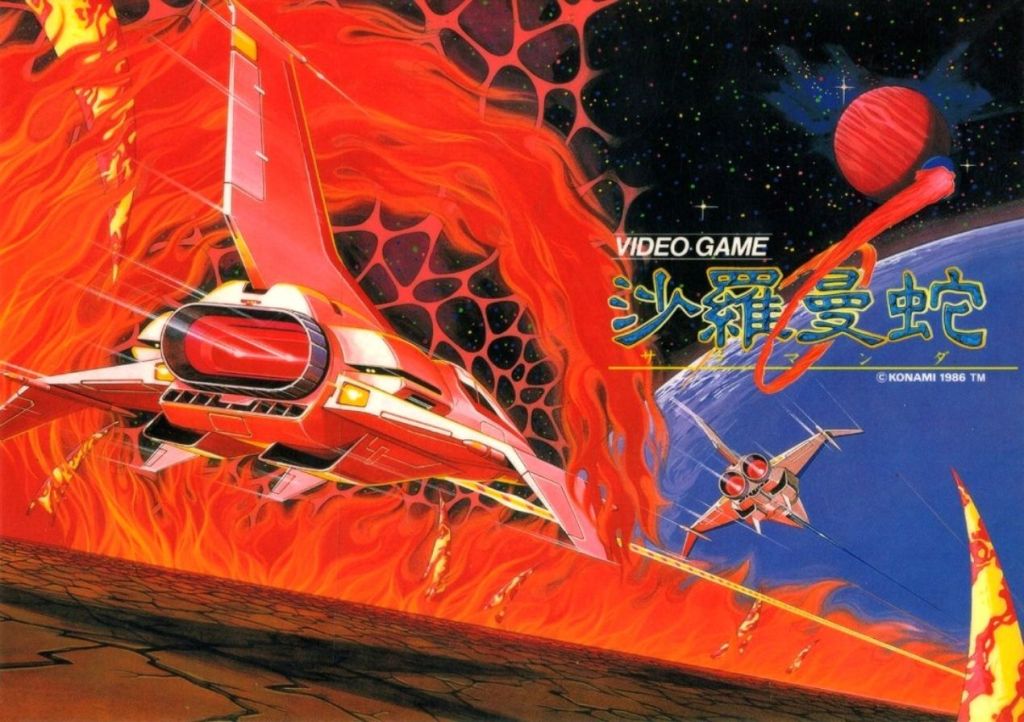

That successor arrived with a fascinating and tangled family tree. The game’s story begins in Japanese arcades in 1986 not as Life Force, but as Salamander, a spin-off to Gradius designed for faster, more frantic action. It introduced two revolutionary ideas: a mix of horizontal and vertical-scrolling stages and a simultaneous two-player co-op mode. Crucially, it ditched the strategic Gradius power meter for a more standard system where enemies dropped specific power-up icons.

When Konami brought the game to North American arcades, they didn’t just translate it. They performed a radical thematic overhaul, rebranding it as Life Force and recasting the entire adventure as a journey inside the body of a giant alien organism. Starfields were replaced with pulsating organic webbing, and digitized voices announced your grisly journey. The story took another twist when Japan released a third arcade version, this one also called Life Force, which fully embraced the organic theme but, critically, brought back the beloved Gradius-style power-up meter.

The NES game we know and love is not a direct port of any single one of these. It was the perfect hybrid, a “greatest hits” that took the best ideas from all versions to create the definitive experience. It was the sequel we never knew we needed, and it was perfect.

Anatomy of an 8-Bit Masterpiece

What makes Life Force a titan of the NES library is its masterfully tuned gameplay. It felt familiar to Gradius fans but was supercharged with fresh ideas. At its core was the return of the strategic power-up system. You would blast specific enemy waves to collect glowing orange capsules, lighting up your power meter at the bottom of the screen: Speed Up, Missile, Ripple, Laser, Option, Shield. Do you cash in that first capsule for a desperately needed speed boost, or do you hold out, risking destruction for the all-powerful Option satellite? This constant risk-reward calculation elevated the game beyond a simple twitch shooter. The arsenal was classic Konami, but the star was the new Ripple laser, a weapon firing expanding rings that provided incredible screen coverage and would become a series staple.

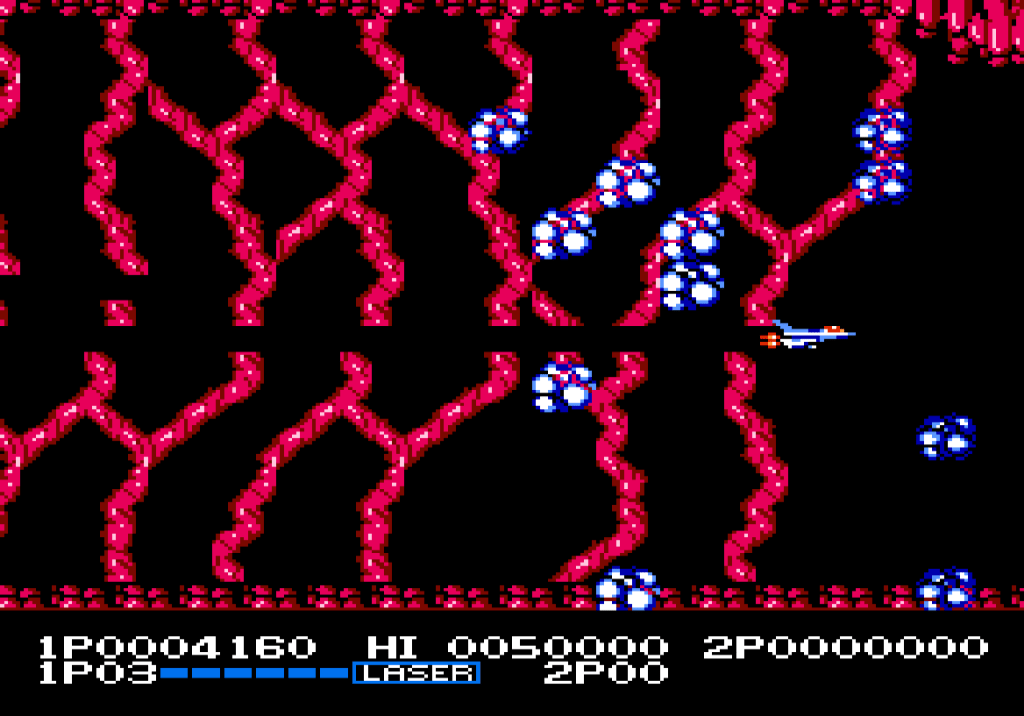

The game’s signature feature was its brilliant alternation between horizontal and vertical scrolling stages. One moment you were flying left-to-right through a fleshy cavern, the next you were ascending a volcanic core from bottom-to-top. This was a technical marvel on the 8-bit hardware, effectively merging two shooter subgenres into one cohesive package. It kept the action from ever feeling stale, forcing you to constantly adapt your strategies.

The real game-changer was the two-player simultaneous cooperative mode. This was the feature that made Life Force a legend. Player 1 took the blue Vic Viper, Player 2 the red Lord British, and together you faced the alien hordes. The level design often felt built for two ships, encouraging teamwork to cover the screen. But this was couch co-op, so it also came with a healthy dose of friendly rivalry. Power-up capsules were a shared resource, leading to frantic dashes to grab them first. Even better, when a player died, their collected Options would float freely for a moment, letting a quick partner swoop in and steal them. You could even “steal” a life from your buddy’s stock if you ran out, a feature that led to more than a few heated living room debates.

Finally, Konami made one of the most player-friendly design choices of the era. They replaced the punishing checkpoint system of Gradius with an instant respawn. When you died, you were immediately back in the action at the same spot. While you still lost your hard-earned power-ups, this single change eliminated the momentum-killing frustration of its predecessor, shifting the focus from perfection to pure perseverance.

Symphony of Destruction

The journey itself was an unforgettable trip through a bio-mechanical nightmare world. You blasted your way through Stage 1’s claustrophobic, regenerating cell walls to face the Golem, a giant brain with a single cyclopean eye. You ascended Stage 2’s volcanic core, dodging asteroids and turrets to fight the spinning mechanical terror, Tetran. You survived the visual spectacle of Stage 3, weaving through massive, screen-filling solar flares that still feel technically impossible for the NES.

Then came the new levels created just for the console release. Stage 4 was a frantic, high-speed vertical ascent through a ribbed-cage cavern, culminating in a battle against a giant, grinning skull whose eyeballs could detach to attack you independently. And then there was Stage 5. In a moment of pure Konami magic, the game completely abandons its biological theme for an ancient Egyptian temple, complete with hieroglyphs, falling spikes, and a giant floating pharaoh’s mask for a boss. It made no sense, and we loved it for that. The final assault took you into Zelos’s mechanical heart for a final boss battle, followed by a heart-pounding, high-speed escape sequence that was the perfect climax to the adventure.

This incredible journey was wrapped in an audiovisual package that represented a high-water mark for the system. The sprite work was detailed and imaginative, the colors were vibrant, and the animations were fluid. In a stroke of genius, Konami’s programmers removed the entire HUD during boss battles. This technical choice, likely made to free up processing power, had a brilliant artistic side effect. It transformed each boss fight into a focused, cinematic duel, stripping the screen down to just you, the monstrous enemy, and a pure black void. And the music.

The soundtrack, co-composed by legends like Miki Higashino of Gradius and Suikoden fame, is simply one of the greatest on the NES. Each track is a high-energy chiptune masterpiece, from the heroic anthem of Stage 1 to the frantic beat of the Temple stage. It’s a score that has been burned into the memory of a generation.

The Undying Organism

Upon its release, Life Force was showered with praise, cementing Konami’s reputation as a technical powerhouse that could deliver arcade-perfect experiences to the home. But its legacy is so much more than that. An argument can and should be made that the NES port is not just a great version, but the definitive version of the game. By cherry-picking the best mechanics from its arcade parents, adding two massive new stages, and perfectly balancing the difficulty for a home audience, Konami created an experience that surpassed its origins in every meaningful way.

Today, Life Force is rightly regarded as one of the best shmups on the console. Its true, lasting impact might be its role as the perfect gateway to a notoriously difficult genre. The game was tough, but its forgiving respawn system made it feel fair. And if it was still too much, there was always the Up, Up, Down, Down, Konami code that gave you and a friend 30 lives, transforming the game from a brutal challenge into an accessible adventure. It allowed players of all skill levels to see every stage, fight every boss, and learn the core skills of the genre without hitting an impossible difficulty wall. It taught us about pattern recognition, strategic upgrading, and how to dodge a screen full of bullets.

Life Force was more than a game. It was a shared experience. It was the thrill of powering up your Vic Viper into an unstoppable death machine, the panic of navigating an eruption of solar flares, the laughter that came from stealing your friend’s last life, and the triumph of making that final, high-speed escape. It was a Frankenstein’s monster of a game, stitched together from the best parts of multiple arcade versions and brought to life on the NES as something greater than the sum of its parts. It was, and still is, a bio-mechanical masterpiece.

Leave a comment