What happens in Vegas, stays in Vegas

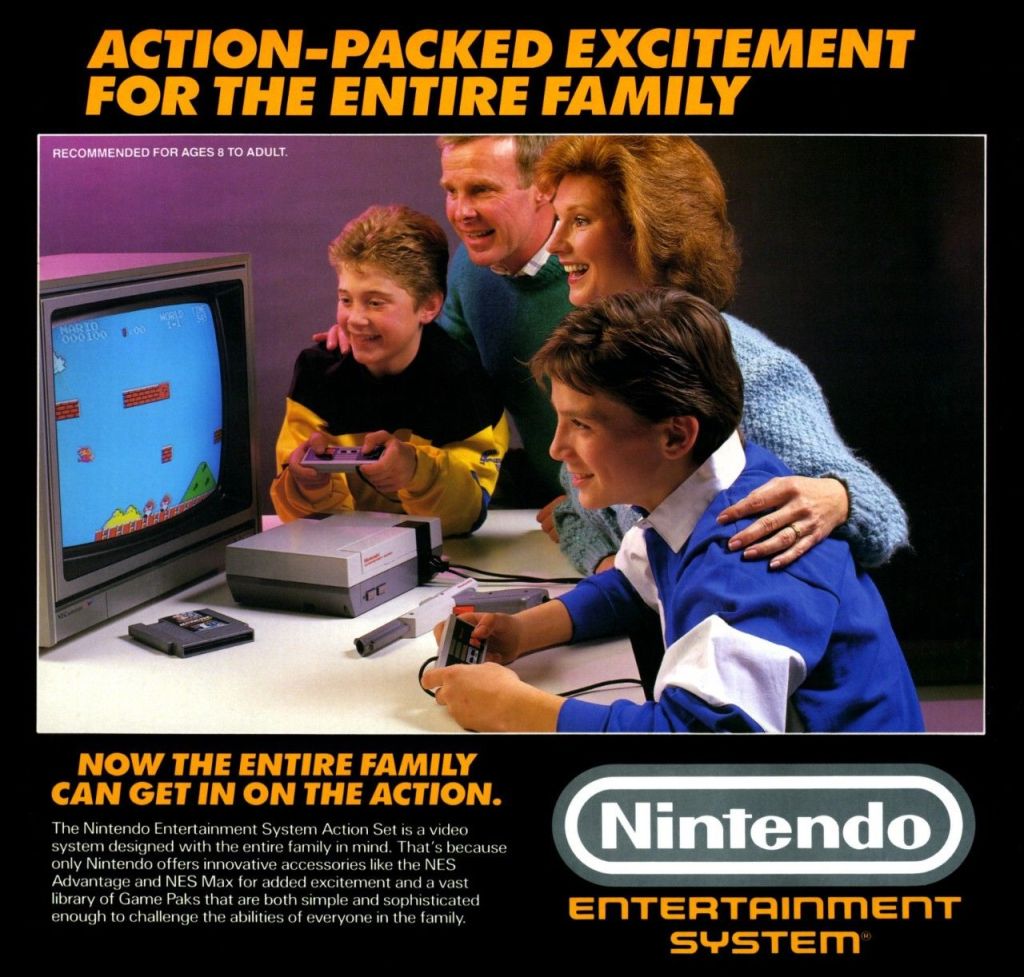

Remember the hiss of a television powering on, the electric hum that filled a quiet room before the 8-bit theme music kicked in? For most of us in early 1989, that was the sound of Nintendo. The world of video games was a simple place. It was a gray box with a black-and-red controller, a universe ruled by a cheerful Italian plumber. The NES wasn’t just a console, it was a cultural fixture, a permanent part of the living room landscape. It had single-handedly saved video games and built an empire so vast and powerful it felt eternal.

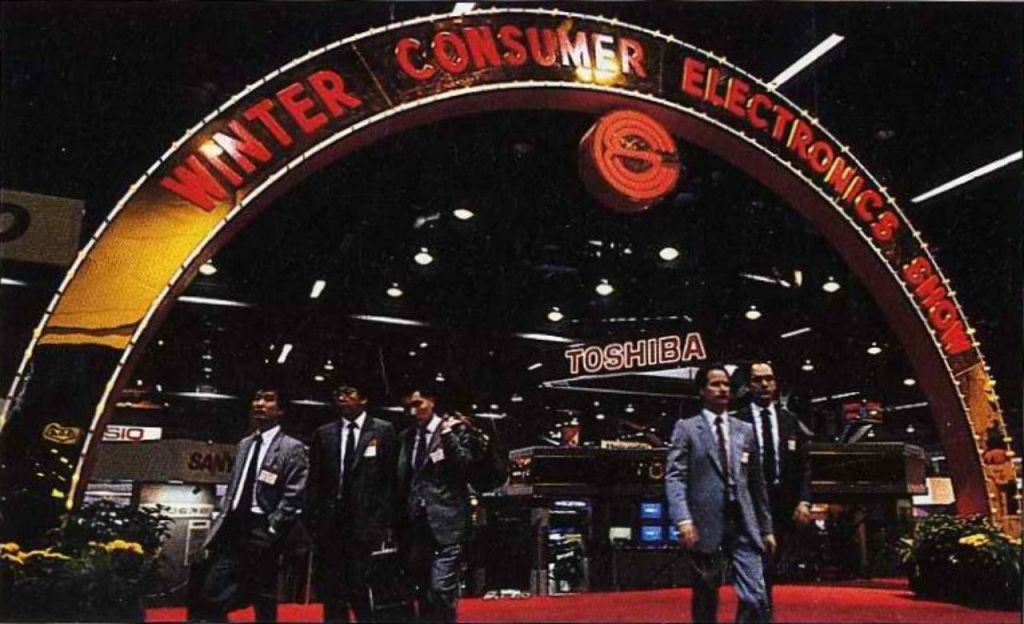

But far away from our suburban cul-de-sacs, in the neon-drenched desert of Las Vegas, the ground was beginning to shake. A rumble was building inside the massive halls of the Winter Consumer Electronics Show. It was the sound of a challenge, a 16-bit roar that was about to turn Nintendo’s victory parade into a street fight for the soul of gaming.

Future Toys

CES had always been a stage for the future. It’s where the world first saw the VCR in the 70s and the CD player in the 80s, gadgets that changed how we lived. Video games had joined the party in the late 70s, but after the great crash of 1983, they nearly disappeared entirely. Nintendo had to sneak back in, brilliantly disguising the NES as a VCR-like “Entertainment System” to calm nervous retailers.

The strategy worked better than anyone could have imagined. By January 1989, Nintendo was the industry. They weren’t just a player, they were the game and their confidence was on full display in Las Vegas. Their booth massive booth was an entire province dubbed “Nintendo City,” a sprawling monument to their 8-bit reign. It was a carnival of gray plastic and beloved characters, a victory lap in front of the entire tech world. Their strategy was clear: expand the empire. They weren’t looking to the next generation, they were focused on accessorizing the current one.

The star of their show was the Power Glove, a futuristic motion controller from Mattel that looked like it was pulled from a sci-fi movie. It promised to let you control games with a flick of the wrist. While it would become a beloved, dysfunctional icon, at that moment it represented Nintendo’s seemingly untouchable innovation. They were so far ahead, they were literally changing how we physically interacted with their world.

The 16-bit Challenger’s to Nintendo’s Throne

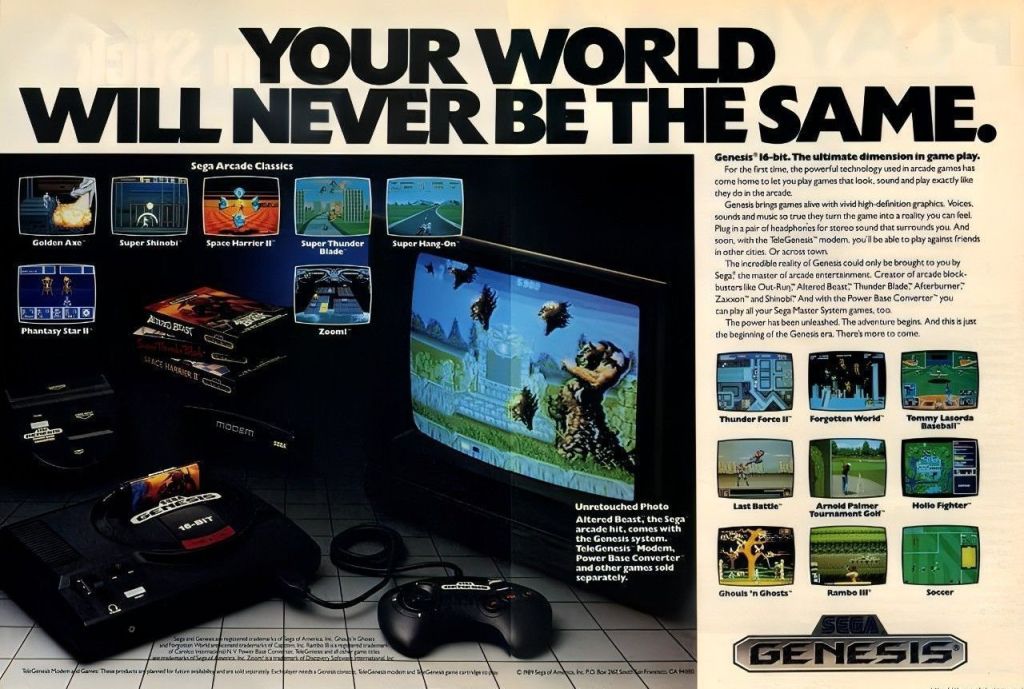

On the other side of the show floor, away from the triumphant fanfare of Nintendo City, a different strategy was taking shape. Sega, a company known for its gritty arcade hits, had come to Vegas with a weapon. Their motivation was born from being a distant second place. They knew they couldn’t beat Nintendo at their own game, so they decided to change the game entirely. Their plan was to target the kids who were starting to feel that Nintendo was for kids. They were going after the teen market with a console that was faster, louder, and undeniably cooler.

On January 9, they made it official: the 16-bit Mega Drive was coming to America as the Sega Genesis. Their strategy was pure arcade aggression. The Genesis was built around the same powerful Motorola 68000 processor found in many arcade machines, and they made sure everyone knew it. They weren’t just selling a console, they were selling the promise of bringing the arcade home. This was a direct shot at Nintendo, whose NES hardware struggled to replicate the true arcade experience. While Nintendo was showing off whimsical peripherals, Sega was letting its games do the talking, and they were talking loud.

And Sega wasn’t the only one. NEC’s TurboGrafx-16 was also making its case. Their strategy was a bet on bleeding-edge technology. Though its main processor was 8-bit, its powerful 16-bit graphics chip put it a step above the NES. More importantly, NEC was showing off the TurboGrafx-CD, the first-ever CD-ROM add-on for a console. They were selling the future, a multimedia world of crystal-clear music and animated cutscenes that made cartridges feel old-fashioned. Nintendo, basking in its 8-bit glory, was suddenly surrounded.

The Games of CES ’89

Walking the floor of the 1989 Winter CES was like stepping into the future. It was a glorious assault on the senses, a digital playground where the games we’d be obsessing over for the next year were on full display. The big picture was staggering; Nintendo announced that its partners were planning to release over 40 new games for the NES in 1989. Not to be outdone, Sega fired back with its own big news, promising 20 new releases for its systems, including hot arcade translations and games in every genre imaginable. For a kid who lived and breathed this stuff, it was heaven.

Inside the gigantic, space-age Nintendo booth, you could feel the confidence of a reigning champion. The main event, the game that had everyone buzzing, was the preview of Super Mario Bros. 3. Contemporary reports highlighted its incredible new features, like Mario’s ability to fly, calling it a game with a level of depth that was ten times that of the original. But Nintendo’s kingdom was vast, showcasing incredible creativity from its partners.

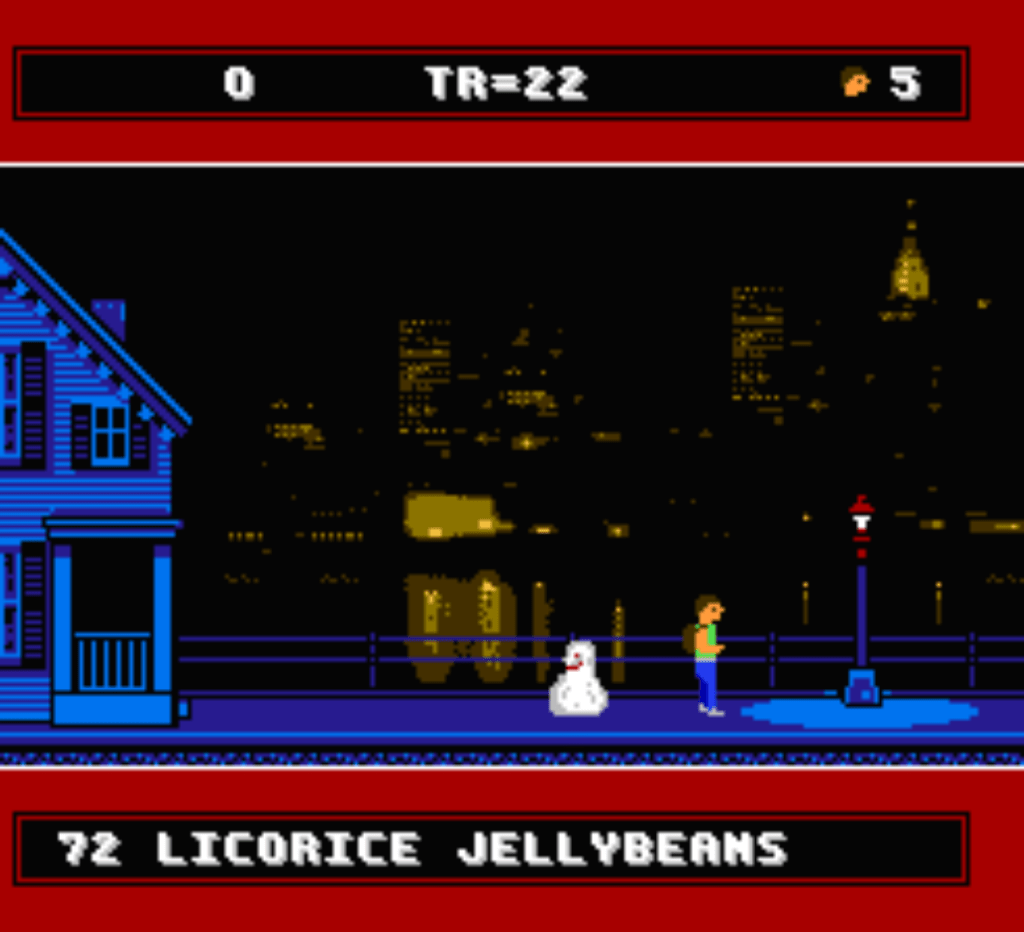

A wonderfully weird and charming puzzle-platformer called A Boy and His Blob: Trouble on Blobolonia, from the creator of Pitfall!, was so unique it won a “Best of Show” award. Nintendo also demonstrated its Power Pad accessory with live aerobic dancers and athletes jumping their way through games like Athletic World and Street Cop.

The entire show floor was a testament to the NES’s dominance, with third-party booths pulling out all the stops. The F.C.I. booth was transformed into a full-blown castle with turrets and battling swordsmen, all to advertise their new adventure game, Ultima.

At the Taito booth, live commandos helped show off their lineup, which included the intense arcade shooter Operation Wolf. Over at the Tecmo booth, a dark and mysterious ninja lurked with a dangerous-looking sword, a living teaser for their coming hit, Ninja Gaiden. Even classic games felt new again, with Mike Tyson’s Punch Out!! being used to show off the futuristic U-Force controller.

But a revolution was brewing. Over at the Sega display, the vibe was completely different—it was all about bringing the arcade home. Sega’s strategy was to prove the power of their new 16-bit Genesis, and their games were the evidence. We saw the incredible sprite-work of Altered Beast, the future pack-in title that let you morph into a monster. They showed off a stunning conversion of the notoriously difficult arcade hit Ghouls ‘n Ghosts and the fast-paced, pseudo-3D action of shooters like Space Harrier II and Super Thunder Blade. To get everyone hyped for their Super Basketball game, Sega even had an indoor half-court set up right on the show floor, complete with a team playing on it.

Beyond the two giants, NEC was offering a glimpse of a different kind of future with its TurboGrafx-16. Its games were chosen to showcase its technological edge. The pack-in title was Keith Courage in Alpha Zones. More impressively, they demonstrated the potential of the TurboGrafx-CD add-on with a port of the arcade brawler Street Fighter, renamed Fighting Street for the console release. They also teased the interactive movie-like experience of It Came from the Desert, hinting at a multimedia future of gaming that felt like science fiction coming to life.

From new adventures for our trusty NES to the 16-bit arcade roar of the Genesis and the high-tech promise of the TurboGrafx, the games of CES ’89 laid out a roadmap for the coming golden age of gaming.

A War for Your Backpack

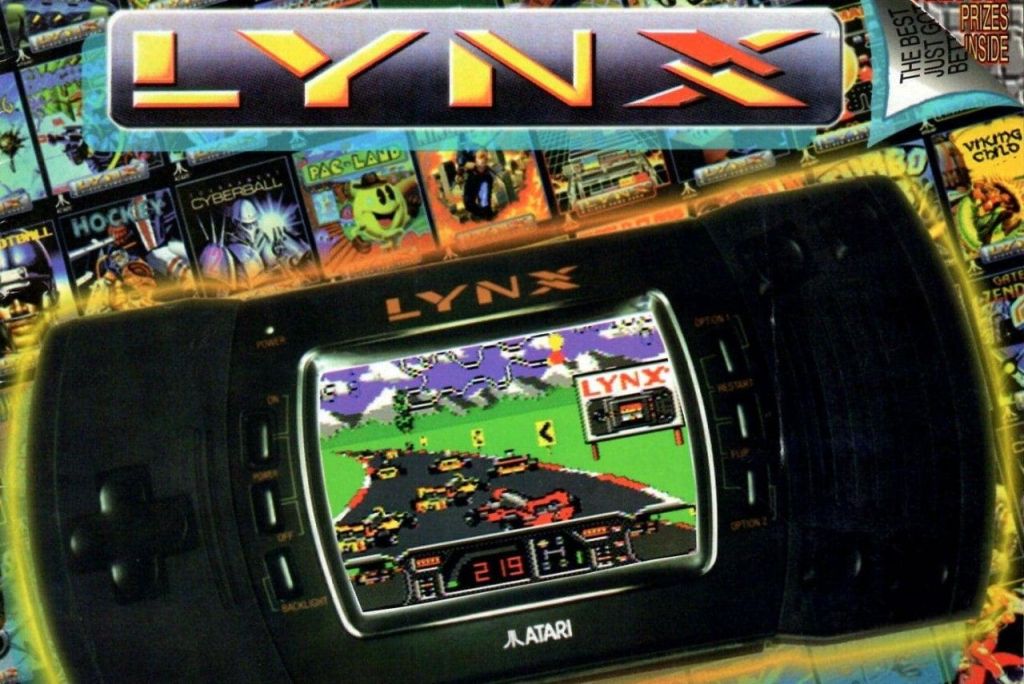

As if the living room wasn’t a big enough prize, a new war was quietly beginning for the space in our backpacks. Atari, the old king of video games, unveiled what would become the Atari Lynx. It was a handheld created by former Amiga engineers, and it was a masterpiece of miniaturization. It had a full-color, backlit screen and powerful hardware capable of scaling sprites for 3D-style effects. It was, in short, a portable console with no compromises. Its strategy was to offer a premium, home-console-like experience on the go.

But lurking like a shadow was the impending release of Nintendo’s Game Boy. Though not shown in Vegas, its philosophy was the exact opposite of the Lynx. It had a simple monochrome screen, but that choice meant it was cheaper and had a ridiculously long battery life. The battle between the powerful, power-hungry Lynx and the accessible, long-lasting Game Boy was a conflict that would define portable gaming for decades.

The Lynx’s launch titles were designed to showcase its advanced capabilities. Games like California Games and a surprisingly good version of Tetris (often considered superior to the Game Boy’s version visually) truly popped on its vibrant, backlit screen. Playing these games felt like carrying a mini-arcade in your hands, a truly revolutionary experience for the time. The fluid scaling effects were particularly impressive, giving a sense of depth and dynamism that no other handheld could even dream of replicating. Atari was banking on the “wow” factor, hoping gamers would prioritize a visually rich, home-console-like experience on the go.

The First Cracks in the Castle Wall

The Winter CES of 1989 was the flashpoint. It was the moment Nintendo’s uncontested rule officially ended. Sega’s brilliant strategy of targeting an older audience with arcade-perfect experiences was a runaway success. Over the next few years, their aggressive marketing and edgy attitude would chip away at Nintendo’s market share, bringing them to a near 50/50 split in North America. This intense competition forced Nintendo’s hand, pushing them to develop and release the Super Nintendo to counter the Genesis threat. The console war that defined our childhoods, the endless schoolyard debates of Mario versus Sonic, all started here.

The show was a crossroads. It was the last moment of the simple, 8-bit world we all knew and the explosive birth of the complex, competitive 16-bit universe we would grow to love. The choices made, the consoles revealed, and the games displayed in that Las Vegas hall created the rivalries that pushed developers to new heights and gave us a golden age of gaming. The empire was no longer safe, and for us gamers, the war was the best thing that ever could have happened.

Leave a comment